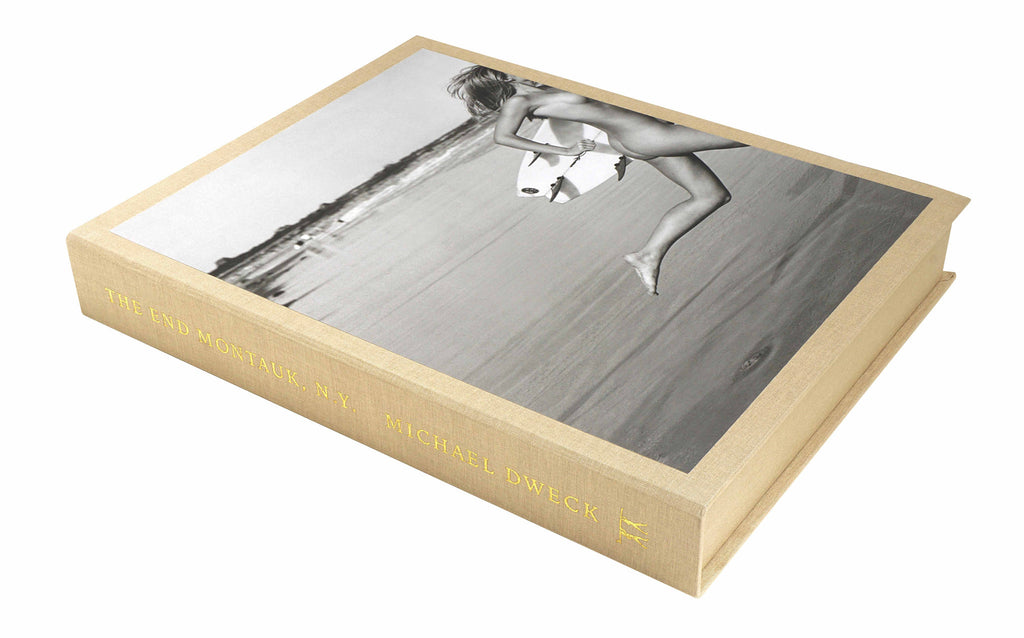

The End: Montauk, N.Y.. Art Edition 'Surf’s Up’, 2016

The End: Montauk, NY

By Michael Dweck

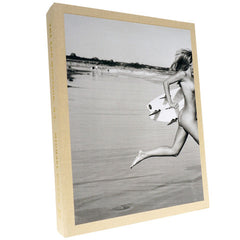

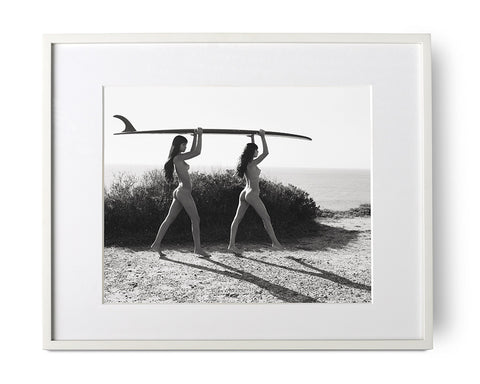

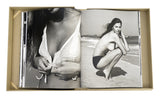

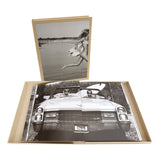

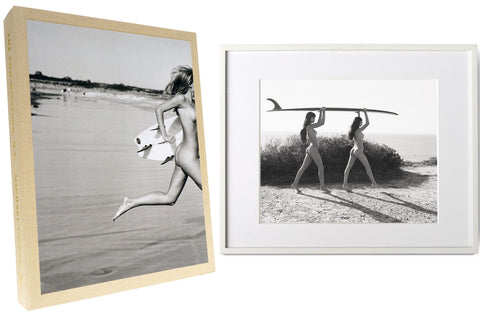

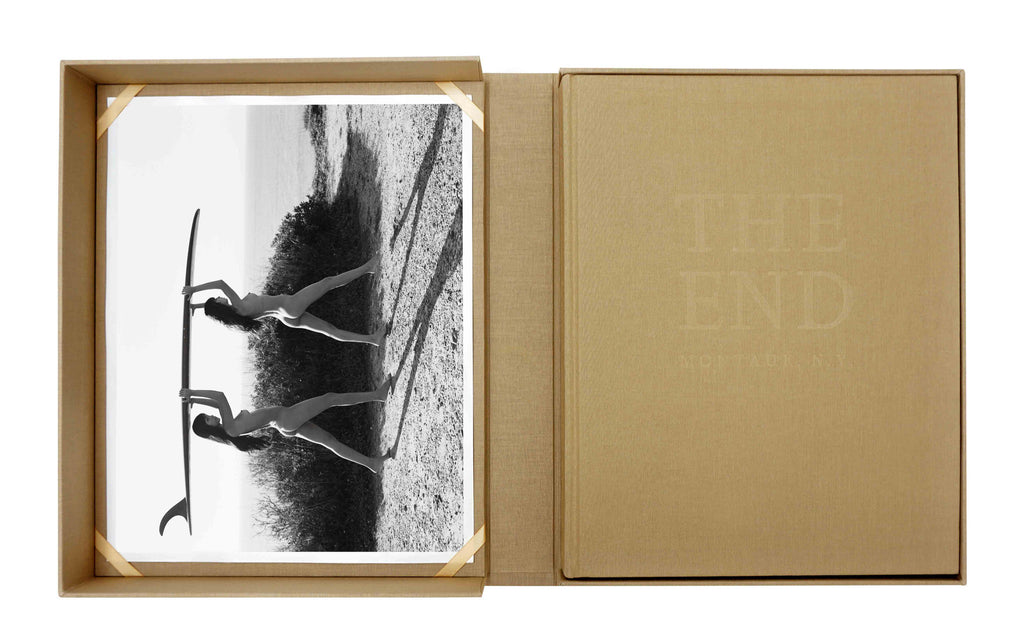

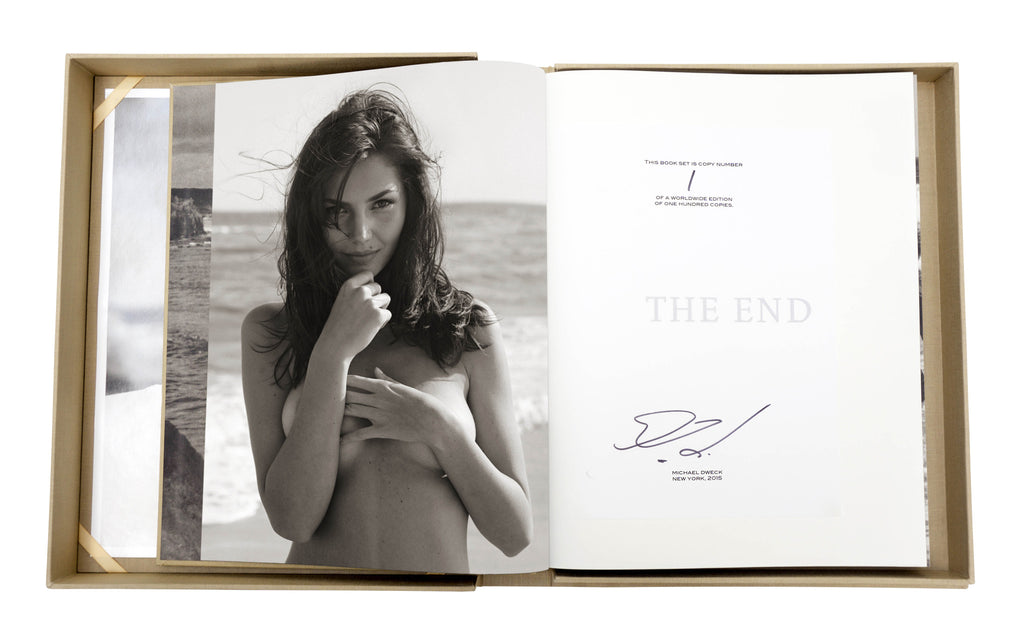

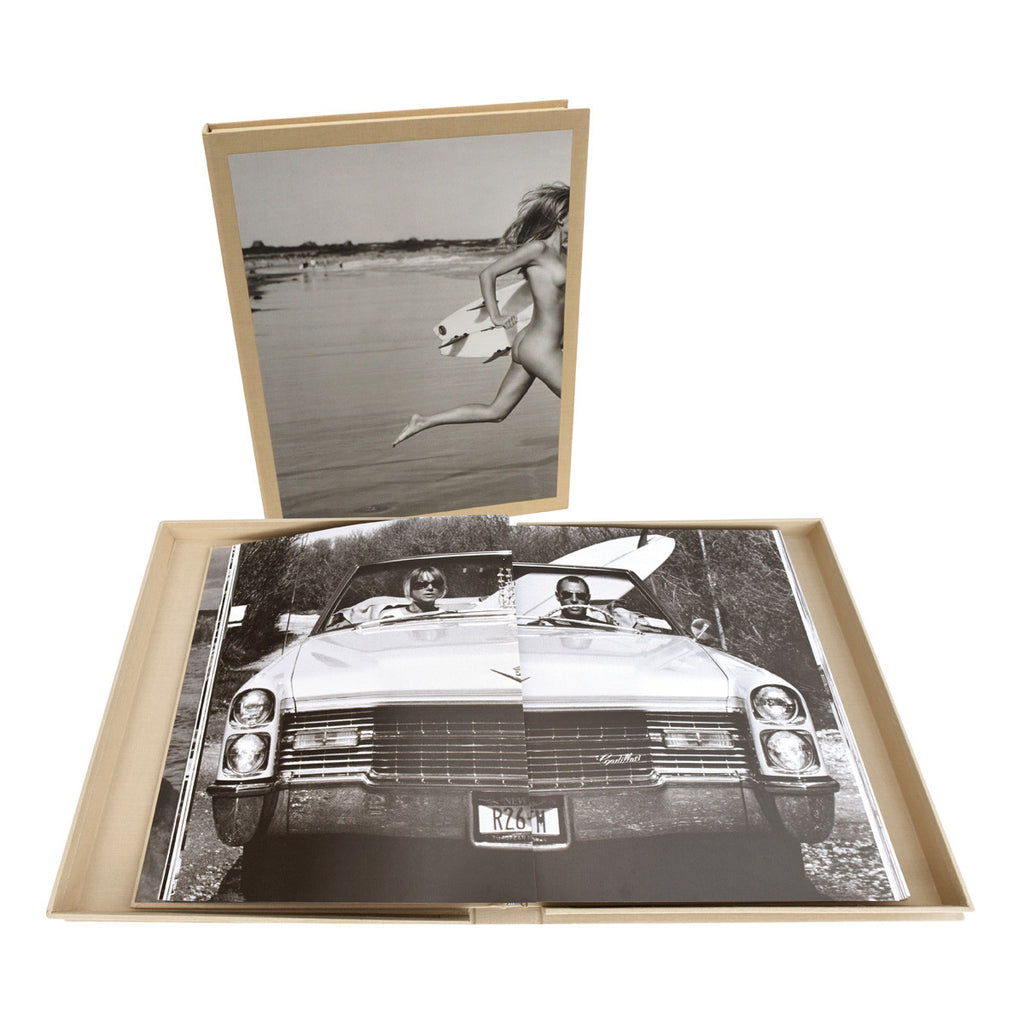

Art Edition limited to 100 numbered copies - clothbound book (256 pages) packaged in clothbound clamshell box, each signed by Michael Dweck, includes the gelatin silver print “Surf's Up” (Montauk, 2006) – format: 35.5 x 28 cm (14 x 11 in.).

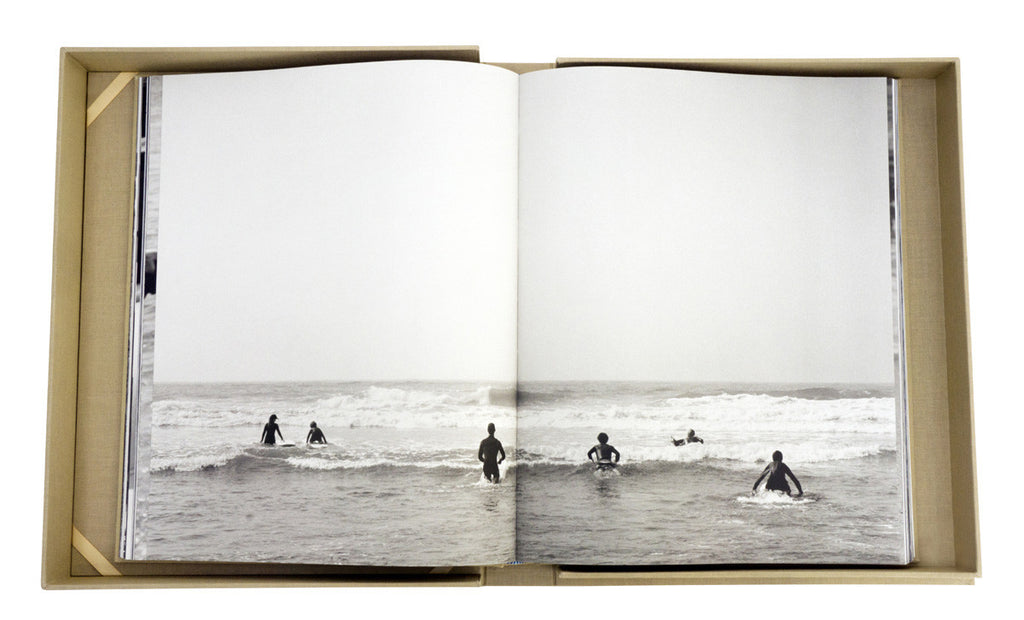

The limited edition printing – originally hailed as “the ultimate homage to the sun-kissed surfing life…” – will feature 85 previously unpublished photos, and a reflective essay by Dweck.

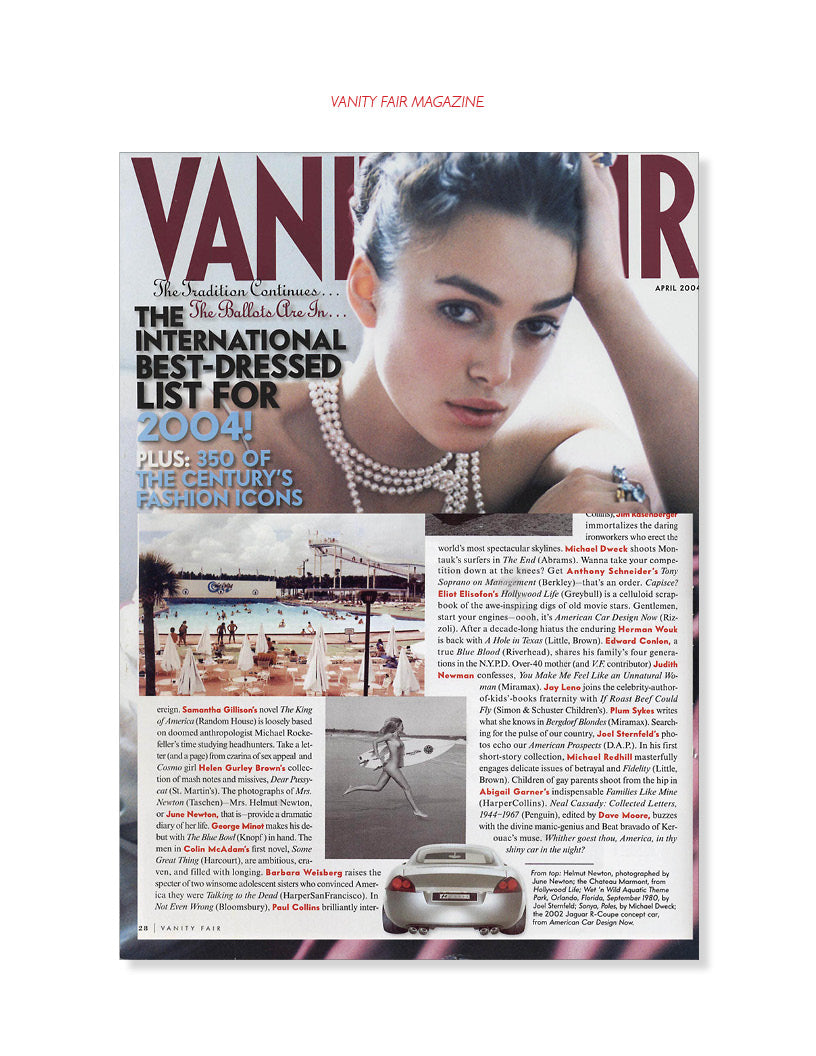

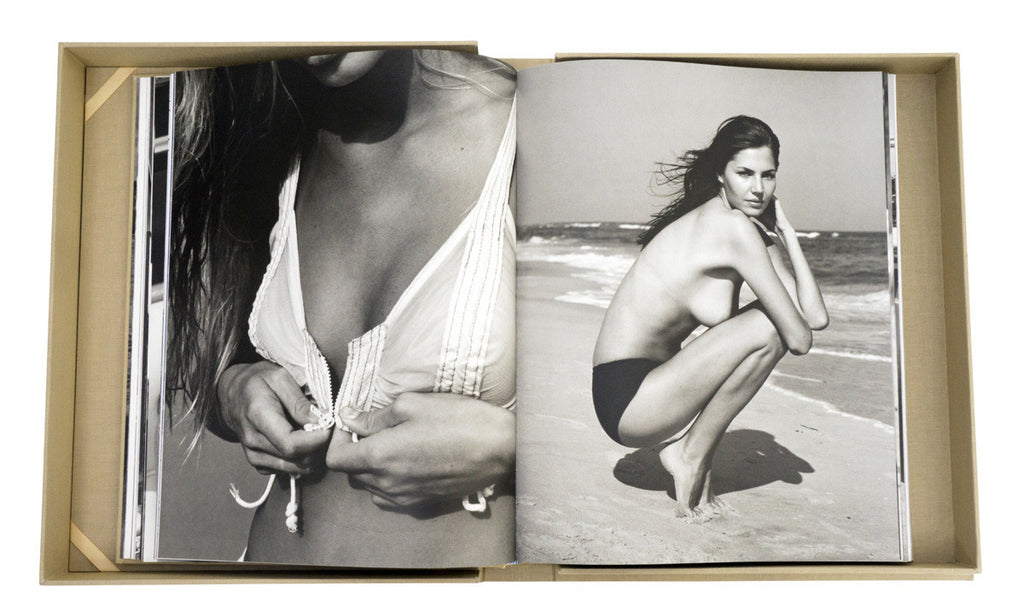

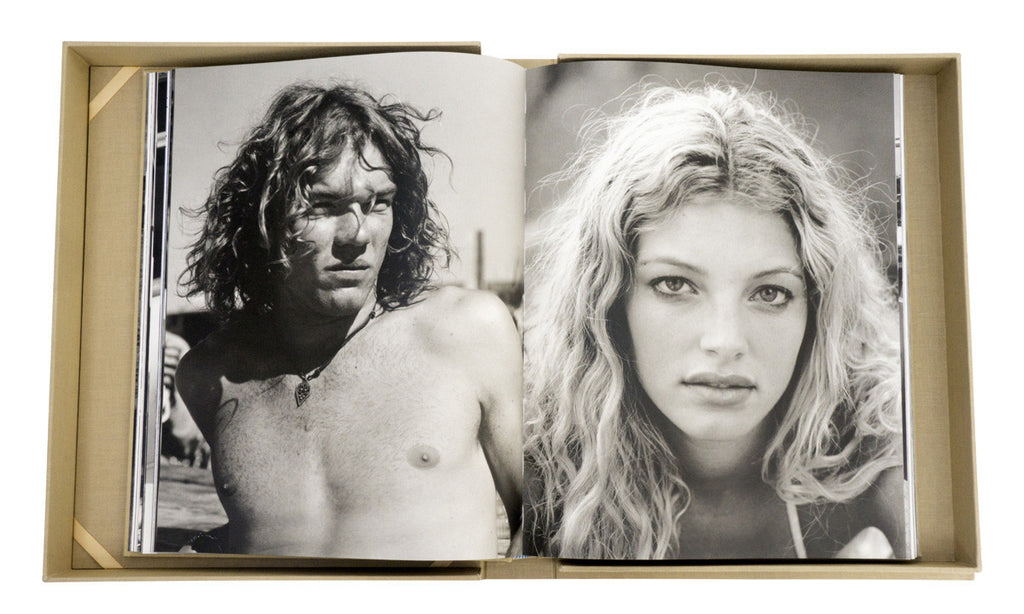

Originally published in 2004, The End presented an idyllic and erotic portrait of the famed Long Island, NY, fishing community, and offered an idealized glimpse into the lives of the beautiful denizens who comprised its surfing subculture. From the dunes of Montauk’s secret surfing haunts, Dweck’s first major photographic work told a paradisiacal narrative about summer and youth, which blended idealism and documentation to reflect a place and a way of life both fading and being reinvented. The original run, as the New York Times noted, “sold out its first printing of 5,000 books in less than three weeks,” and became an instant classic, fueled by its groundbreaking narrative form, and now-iconic images like the cover’s nude, “Sonya”, “Dave and Pam in their Caddy”, “Adriana” and “Lilla.”Collectors of fine art photography will relish this rare opportunity to own a signed, numbered, limited edition volume – as well as the gelatin silver print of one of his photographs.

The expanded 10th Anniversary Art Edition Box Set of The End: Montauk, N.Y. (limited edition of 300) examines the legacy of this original work, but also addresses the myriad of changes Dweck predicted when he first turned his camera to Montauk in early 2000.

Printed in Italy, each copy will be signed and numbered, and packaged in a handmade, cloth-lined clamshell case, with an exclusive 11x14 silver gelatin print, also signed and numbered.

A portion of the proceeds from the sale of The End: Montauk, N.Y. will go towards maintaining the waterways and beaches of Long Island and the U.S. through the Surfrider Foundation and Operation Splash.

Also available in two other Art Editions (No. 101-200, 201-300) each with alternate silver gelatin photographs signed by Michael Dweck.

Michael Dweck

The End: Montauk, N.Y.

by Christopher Sweet

Michael Dweck’s first major photographic work was published in volume form as The End: Montauk, N.Y., in 2004, and was featured in several exhibitions and art fairs that year. The work portrays the old fishing community of Montauk and its surfing subculture. It is an evocation of a real-world paradise lost: the paradise of summer, youth, and erotic possibility — an American version of the Arcadian vision. Blending nostalgia, fantasy, and documentation the photographs present a compelling portrait of a place in time and a way of life at once fading and being reinvented with each new season.

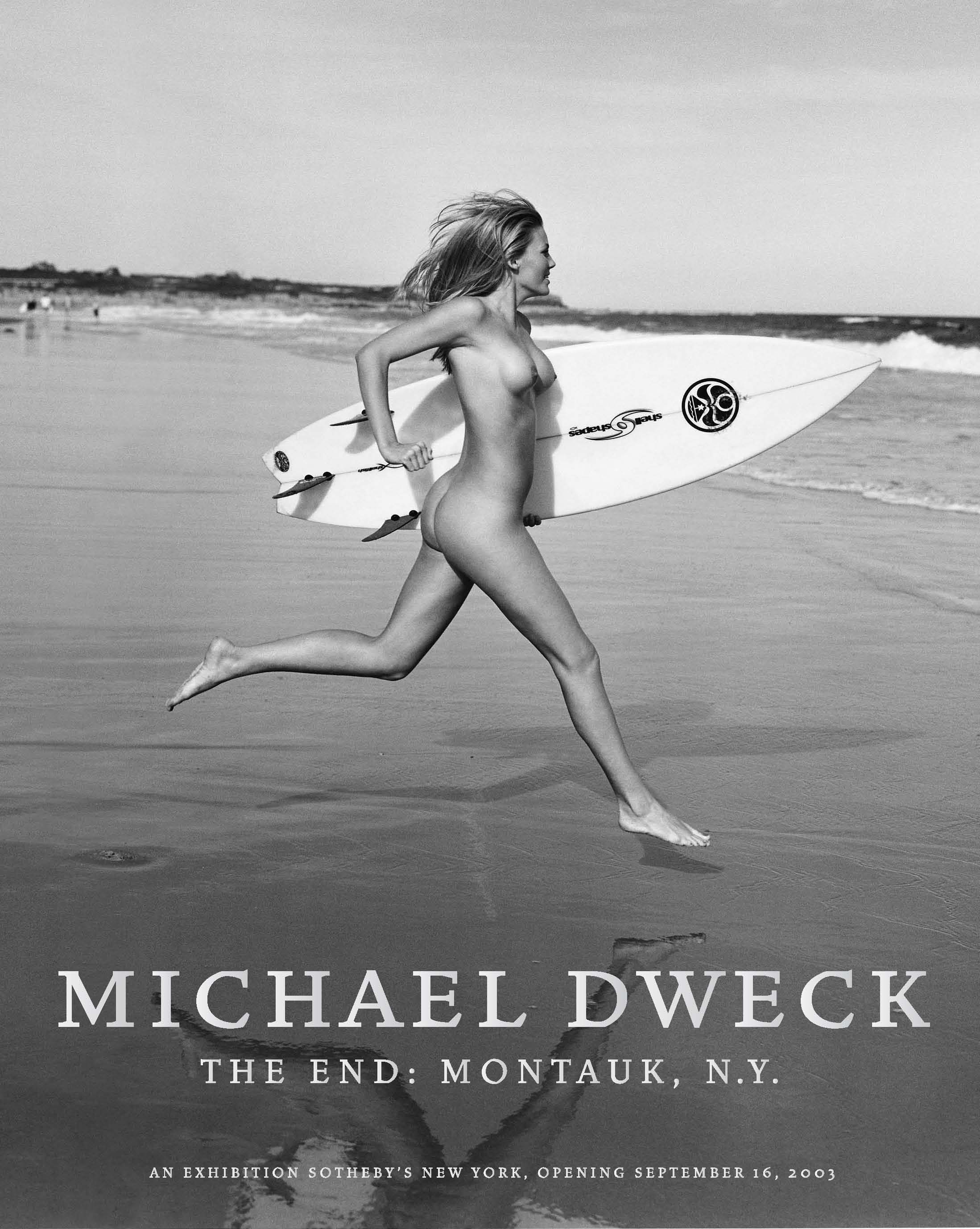

The signature photograph of the collection, Sonya, Poles, is an image of ecstaticsummer. A beautiful young woman in full naked glory — her blond hair blown back, her breasts aloft, a smile of anticipation — bounds across a glistening beach, a surfboard under her arm, toward the incoming waves. In the far distance — in the upper margin of the picture — waves and dunes, surf and scrub fringe the horizon line which divides her head from her body. Her face is profiled against the great sky, and her dynamic body against the flat expanse of wet sand. All the bliss of summer fun and youthful promise is summed up by her scissor kick, reiterated by her shadow and her reflection, a vivacious “v” form that becomes a faceted diamond cleaved from light. And that bolt of white, her surfboard, like a missile, will carve out the place on the wave that will bear her back over the beating tide like a goddess from the sea.

A tattered Old Glory flaps in the wind, an abandoned VW camper sits near theside of the road, beached like a dead whale, its former glory as a Love Bug long lost. Cars pull up in the parking lot near the beach. People slip out of their t-shirts and jeans and into bathing suits. The gear is unloaded. The tribe gathers. Aging sybarites ponder their past glories while oblivious, feckless youth in full flower frolics on the beach, cavorts in the water, sits out on the gentle swells waiting for waves, or makes mischief up at the motel or back at the cottage. Old timers measure the days, the years not by how far they have come, but how close they have remained and yet how much the place and they have changed, how much the weeds have grown up around them like the abandoned camper. An old surfboard, left under a house some twenty, thirty years before finds its original owner just down the road. At night the luau begins and the girls in grass skirts tease the men and boys. And the pleasures of the night beckon.

A few old timers show up, hang out, nowhere else to go, not part of the party butregulars on the scene. They add a little texture, lend a bit of character – like relics and artifacts – and are tolerated, at times perhaps indulged, as long as they don’t bother the girls. They serve as reminders that the past is not just the sound of receding trumpets. The years roll on like the tides, the seasons turn, and each summer brings its own story. With each new year, there is some new development, new blood, and more and more the hazard of new fortunes changing the balance and tone. New arrivals take it as they find it. Only the lifers, of one sort or another, bear the burden of how things ought to be, how things used to be.

Michael Dweck’s The End: Montauk, N.Y., is a private Idaho, a personal Eden, atonce remembered and imagined. The Arcadian setting is a place for recreation, self-invention, and the celebration of physical beauty and well-being and the tender temptations of the flesh. It is a down-home beach paradise of a distinctly American variety, Endless Summer, that blessed but all too brief interlude that separates the seasons of school and work, adolescence and adulthood. Dweck’s vision of the far end of the island mingles the yearnings and anxieties of youth and age, of callowness and conscience, the exuberance of one’s salad days and the frisson of old bachelors. The season in the sun in due course passes into autumn. Youth and beauty blush, exude their sweetness, exert their power, but inevitably falter and fade before the onslaught of the years under the overarching, ozone-depleted sky. Our times are not in our hands. The eviction notice is tied to the gate, even as one enters, and the unease of that knowledge hovers over the good fun. The golden youth of one summer is the worldly-wise veteran or the broken old timer of another. The End is an elegy to the evanescence of youth and an ode to the consolation of art.

Art Edition A, No. 1–100

- The End: Montauk, N.Y. 2015 by Michael Dweck

- Essays by Michael Dweck and others

- Published by Ditch Plains Press

- Large format hardcover: 27.94 x 35.56 cm (11 x 14 in.) with 256 pages, 260 duotone plates, 15 color-plates and 3 gatefolds

- Limited to 100 copies

- Each book numbered and signed by Michael Dweck

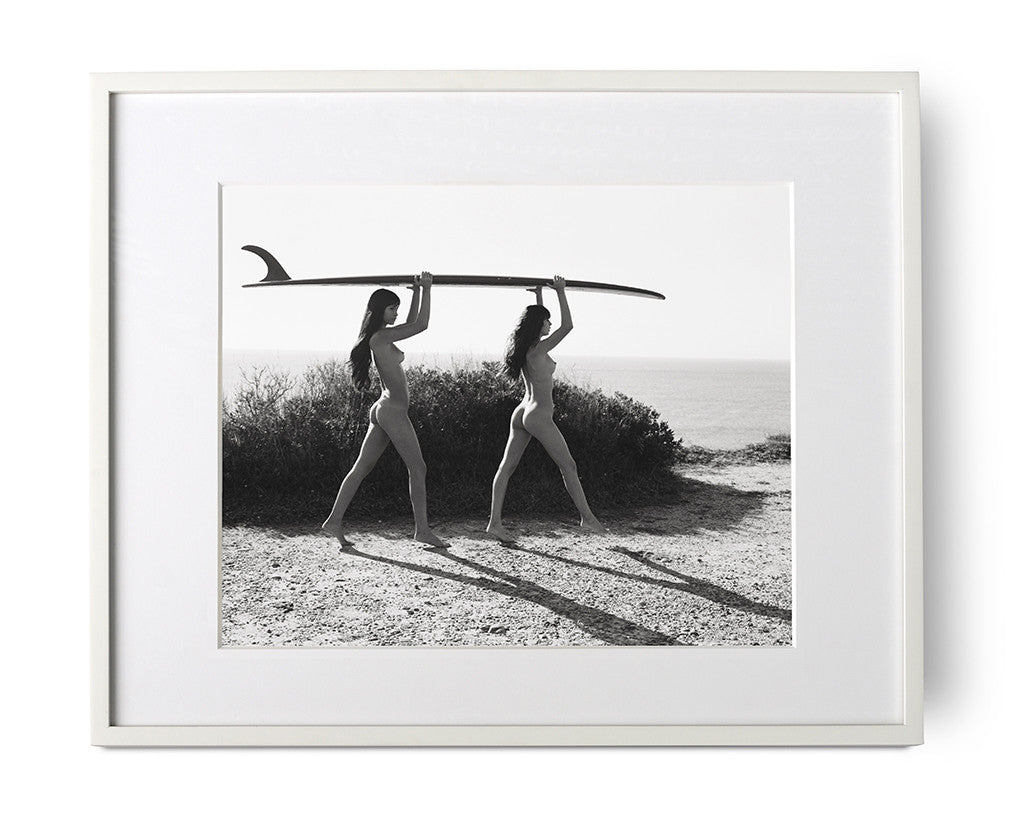

- Includes a gelatin silver print "Surf’s Up", Montauk 2006, signed and numbered by Michael Dweck

- Release date: 2016

- Printed and bound in Italy

- ISBN 978-0-9818465-1-4

- Oversize clothbound clamshell box 31.7 x 39.4 x 5.7 cm. (12.5 x 15.5 x 2.25 in.)

The duotone illustrations are made with a special treatment for black and white images that produces exquisite tonal range and density. All color illustrations are color-separated and reproduced in the finest technique available today, which provides unequalled intensity and color range.

About Michael Dweck

Michael Dweck is an American photographer, filmmaker and visual artist.

His work has been featured in solo exhibitions around the world, and become part of important international art collections. Notable solo exhibitions include Montauk: The End, 2004, a paradisiacal and erotic surf narrative set on Long Island; Mermaids, 2009, which explored the female nude refracted by river waters; and Habana Libre, 2010; an intimate exploration of privileged artists in socialist Cuba, which made him the first living American artist to have a solo exhibition in Cuba. These and other works have also been published in large, limited-edition volumes.

Previously, Dweck studied fine arts at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York and went on to become a highly regarded Creative Director, receiving more than 40 international awards, including the coveted Gold Lion at the Cannes International Festival in France. Two of his long-form television pieces are part of the permanent film collection of The Museum of Modern Art in New York. Michael Dweck currently lives in New York City and Montauk, N.Y., where he is finishing his first feature-length film.

“the ultimate homage to the sun-kissed surfing life…”

– New York Times

Includes signed and numbered

Surf’s Up, Montauk 2006

silver gelatin print

27.94 x 35.56 cm / 11 x 14 in (paper size)

(Frame not included)

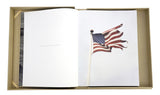

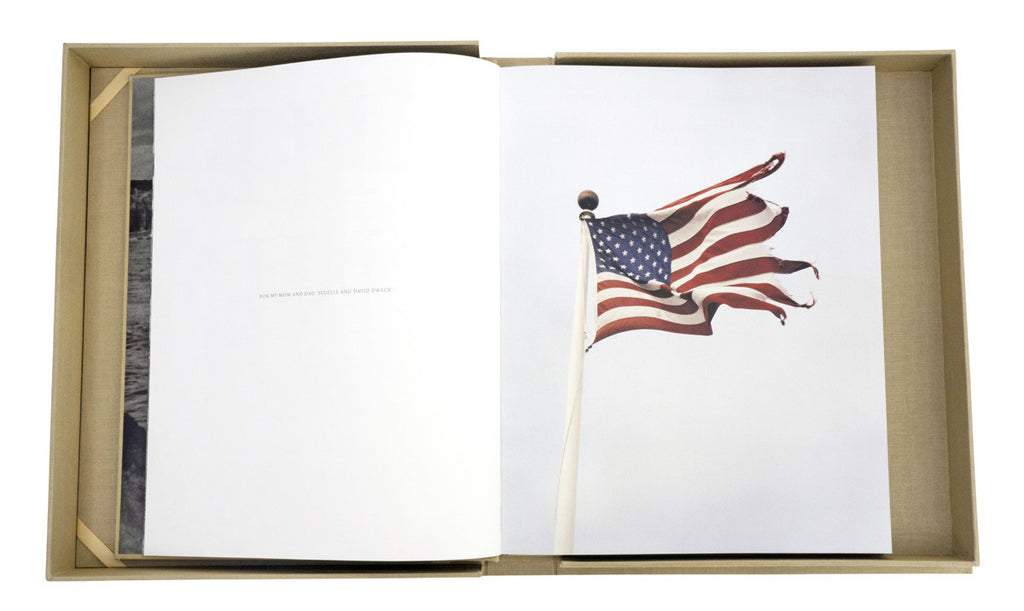

Flag at Snug Harbor, Montauk 2002

Flag at Snug Harbor, Montauk 2002  Adriana at The Panoramic View, Montauk 2002

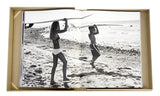

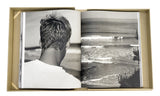

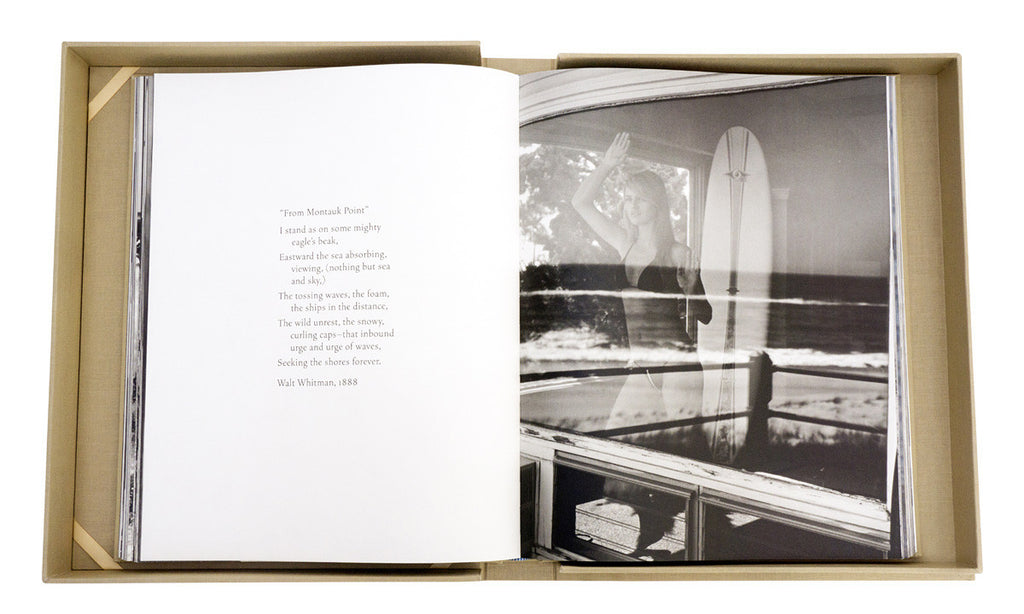

Adriana at The Panoramic View, Montauk 2002  Surf’s Up, Montauk 2006

Surf’s Up, Montauk 2006  Lilla, Nappeague 2002

Lilla, Nappeague 2002  Old Boards at Tony’s House

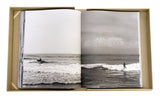

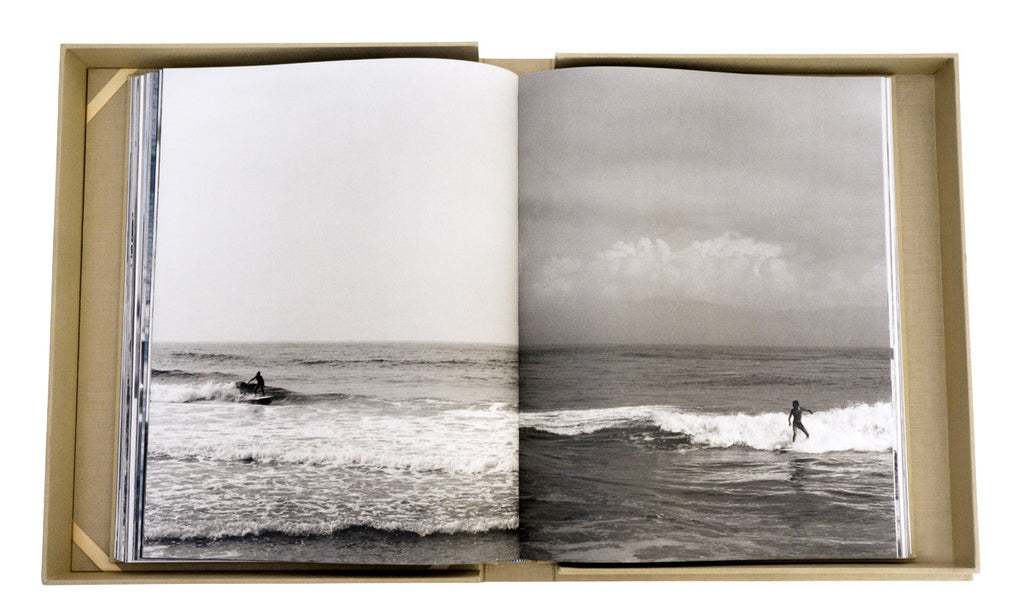

Old Boards at Tony’s House  Surfing at Ditch Plains, Montauk 2002

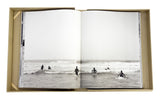

Surfing at Ditch Plains, Montauk 2002  Ray, Montauk 2002

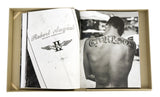

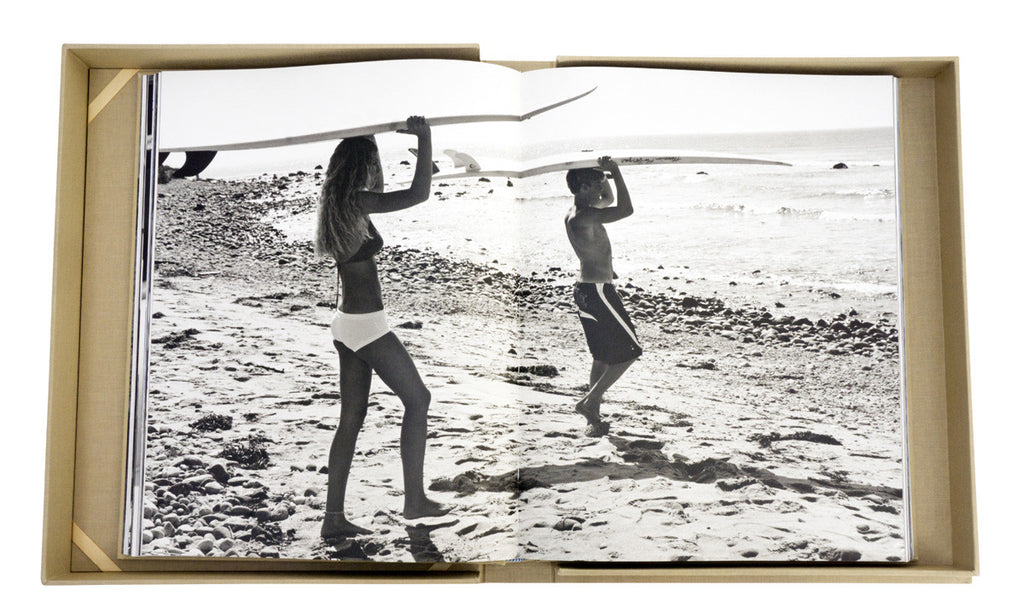

Ray, Montauk 2002  Morning surf at Poles, Montauk 2012

Morning surf at Poles, Montauk 2012  Jessica and Kurt, Montauk 2002

Jessica and Kurt, Montauk 2002  Getting wet, Cavett’s Cove Montauk 2006

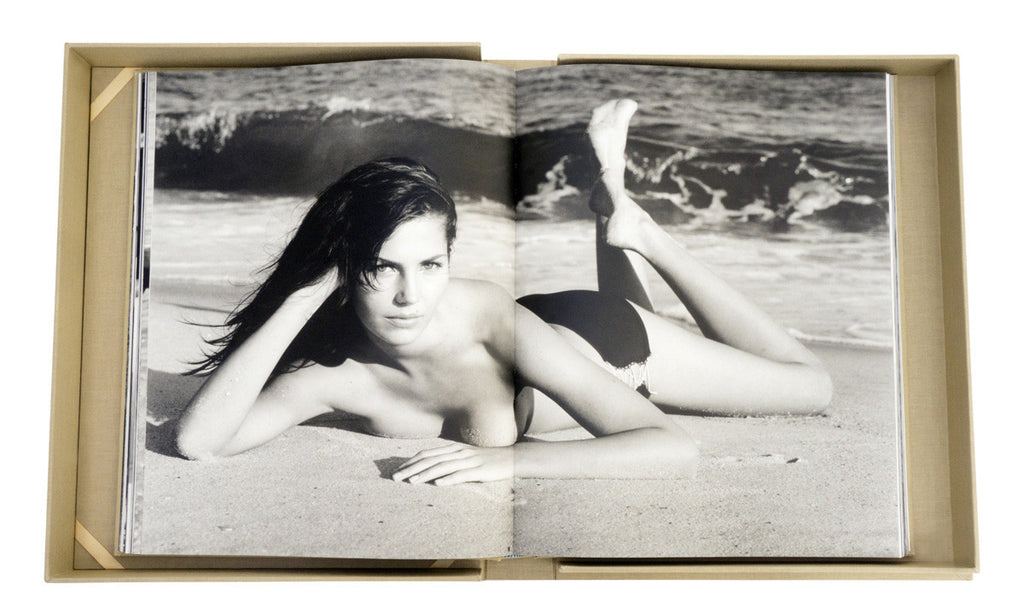

Getting wet, Cavett’s Cove Montauk 2006  Laying out, Montauk 2012

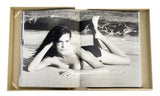

Laying out, Montauk 2012  Lilla, Nappeague 2002

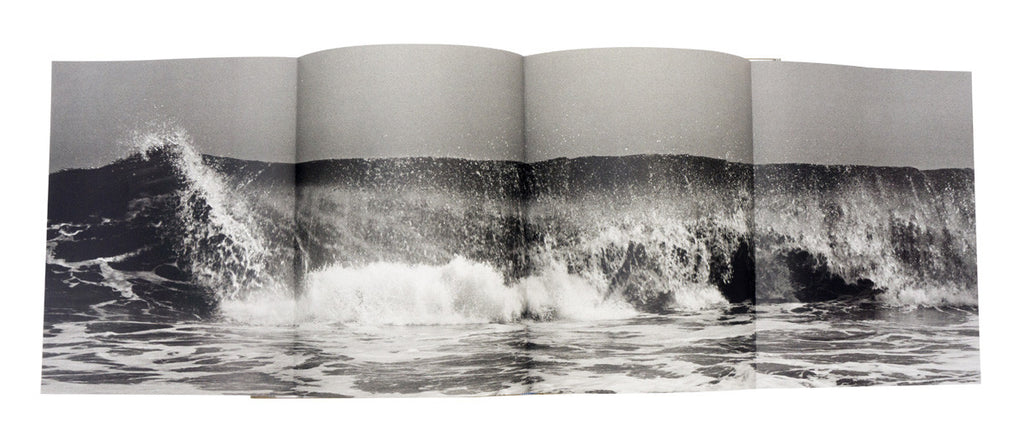

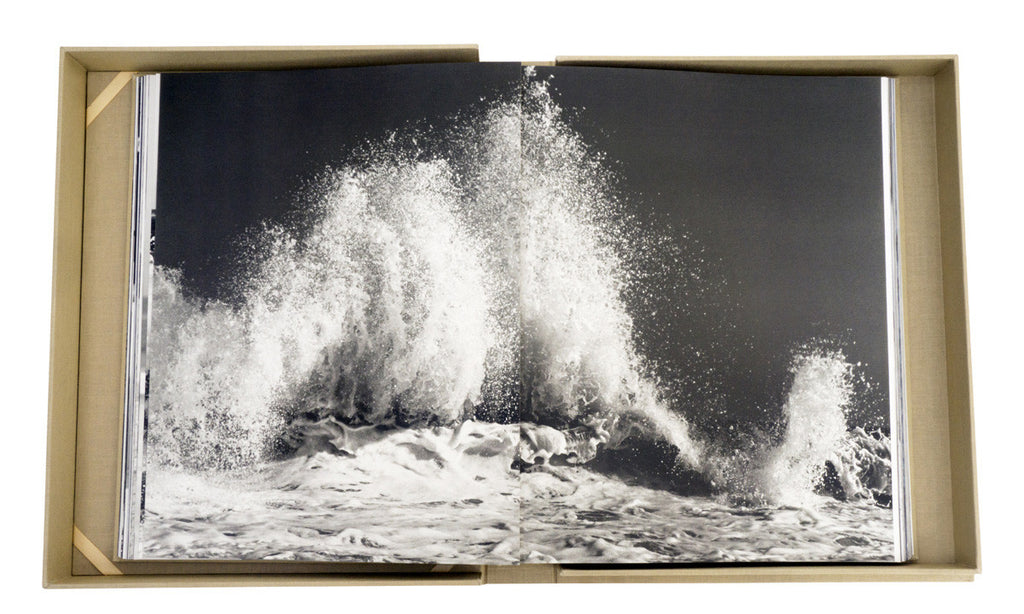

Lilla, Nappeague 2002  Wave after the storm, Montauk 2009

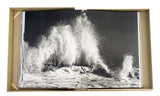

Wave after the storm, Montauk 2009  Cooling off, Turtle Cove, Montauk 2012

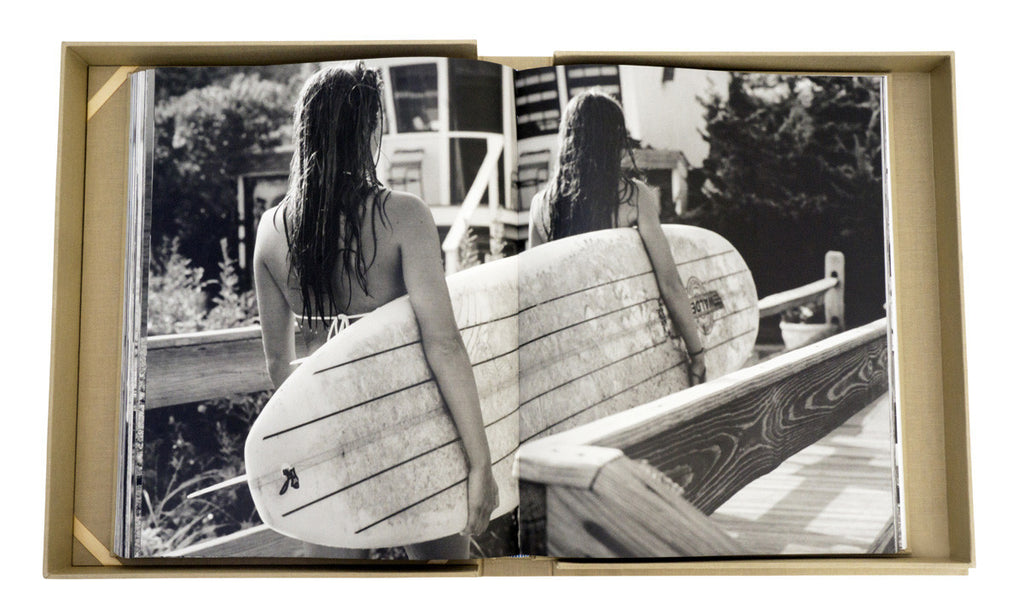

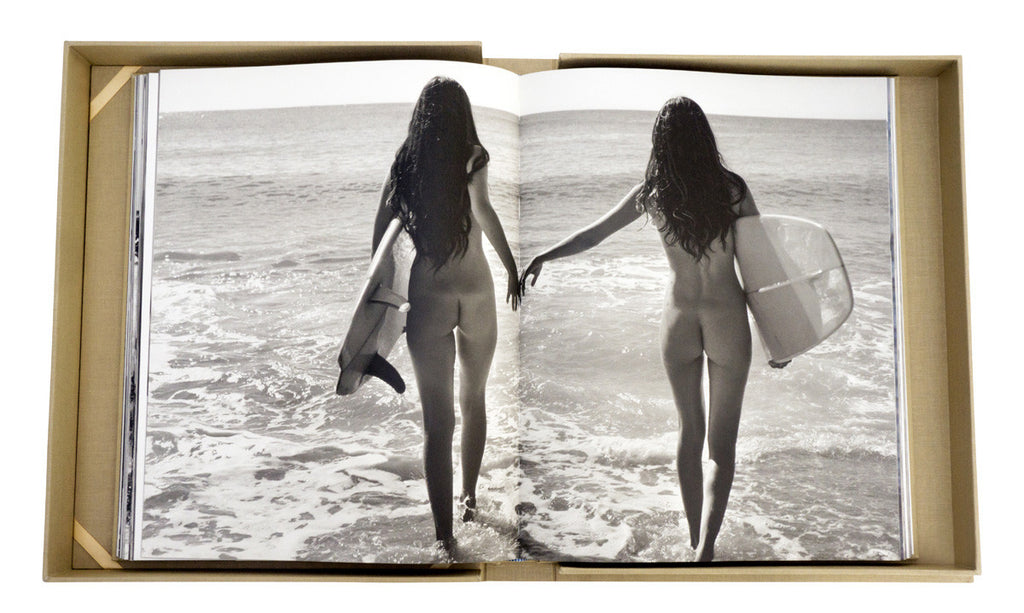

Cooling off, Turtle Cove, Montauk 2012  Julia and Brittany, Hither Hills/Apres surf, Montauk 2012

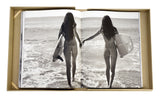

Julia and Brittany, Hither Hills/Apres surf, Montauk 2012  Lilla, Nappeague 2002

Lilla, Nappeague 2002  Natalie on the Rocks, Camp Hero, Montauk 2008

Natalie on the Rocks, Camp Hero, Montauk 2008  Surfing Air Force Base, Montauk 2013

Surfing Air Force Base, Montauk 2013  Calm Before the Storm, Montauk 2008

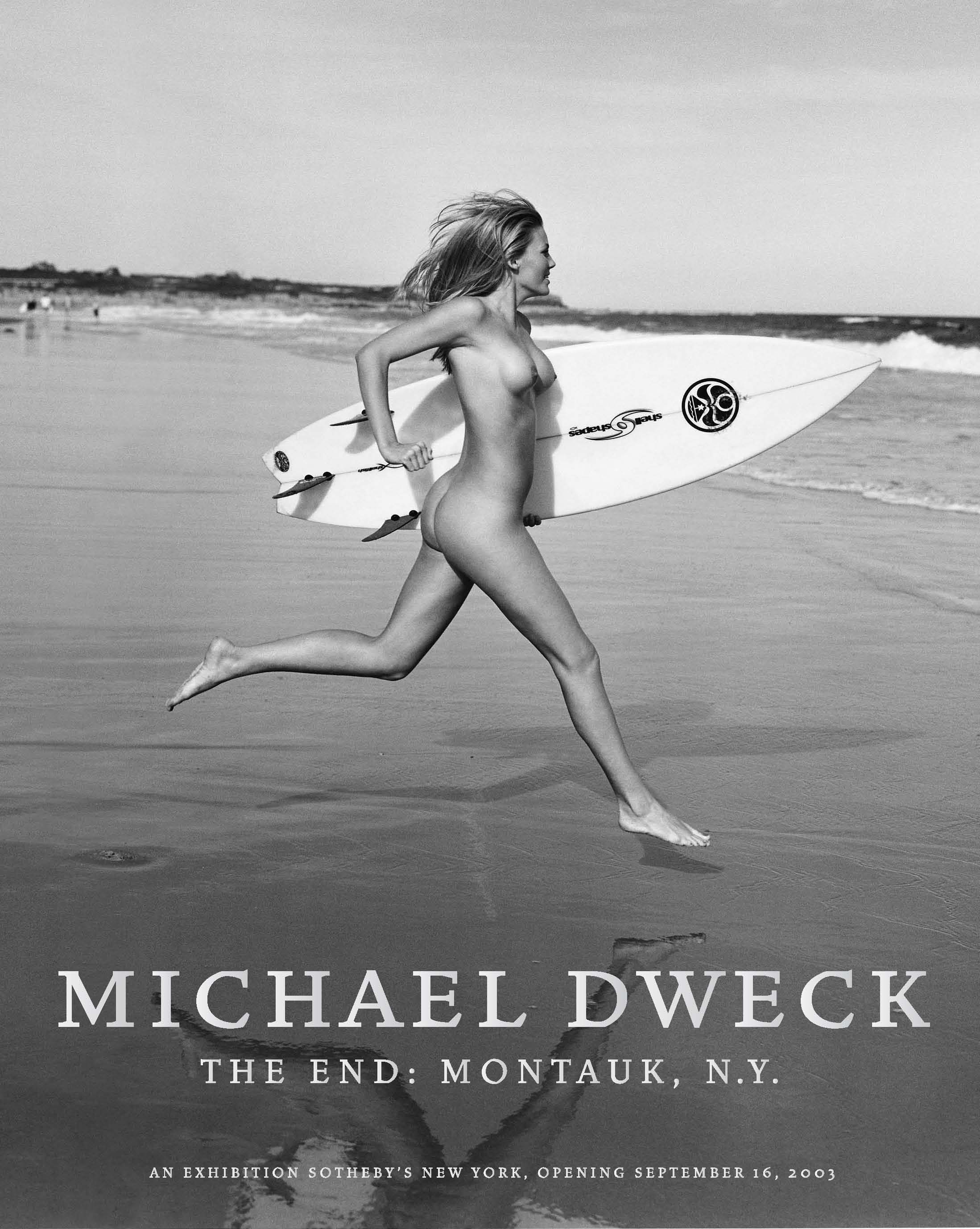

Calm Before the Storm, Montauk 2008  Poster from the Sotheby’s exhibition 2003

Poster from the Sotheby’s exhibition 2003  Sotheby’s exhibition 2003

Sotheby’s exhibition 2003  Sotheby’s exhibition 2003

Sotheby’s exhibition 2003  Sotheby’s exhibition installation 2003

Sotheby’s exhibition installation 2003  Sotheby’s exhibition 2003

Sotheby’s exhibition 2003  Staley Wise exhibition 2012

Staley Wise exhibition 2012  Staley Wise exhibition 2012

Staley Wise exhibition 2012

Michael Dweck The End: Montauk, N.Y

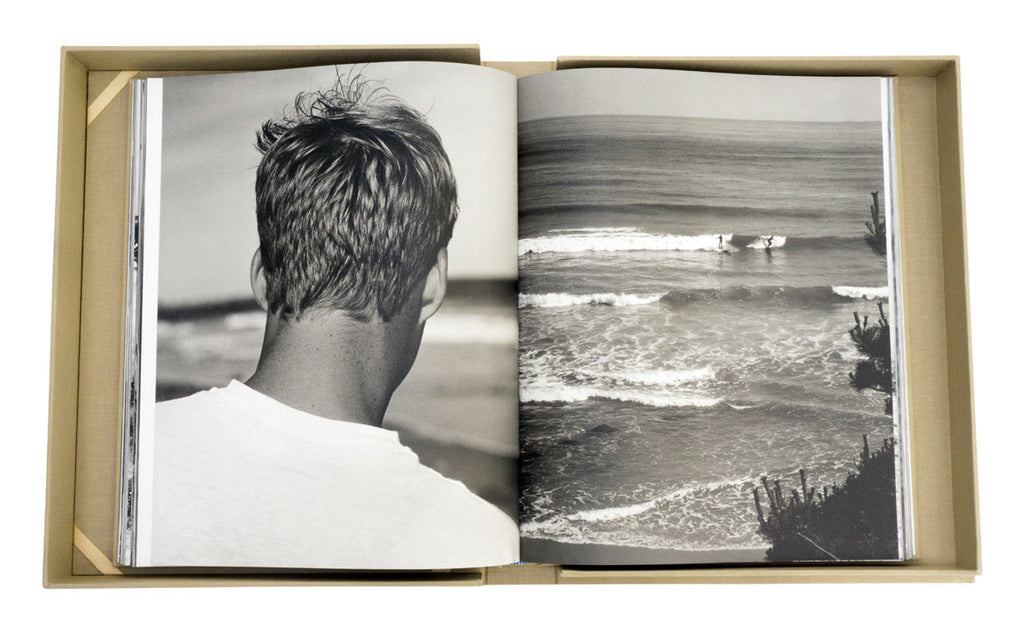

In the 1960s, the fishing village of Montauk became the surfer's paradise of the United States' East Coast. Located as the tip of Long Island's South Fork, the easternmost point of the Hamptons, this paradise existed primarily for locals - not surfers who migrated to the beach for the summer, but those who were out in the rocky reefs every day, year round. Today, a new tribe of surfers exists - a group of young locals who live by their own rules. Rule number 1: Never tell anyone where the good surf spots are. Rule number 2: See rule number 1. In the 1990s, photographer Michael Dweck rented a house on Ditch Plains beach (site of the best surf break) and struck up a friendship with one of the local surfers, eventually gaining uprecedented access to the insular local surf community. Dweck's photographic essay follows the surfers through their daily rituals, from early morning wave reports to evening bonfires on the beach, capturing their youthful hedonism. Through portraits, nudes, and photographs of the landscape, this book celebrates lives lived only to surf, and captures an endless summer of perfect weather and languorous beauty.

Surf Collective Interview with Michael Dweck

Surf Collective

Interview with Michael Dweck

SC: You are a true native and longtime resident of Long Island. You've seen it evolve and change in many ways, especially around Montauk and the areas you pay tribute to in the book. What are your thoughts on the evolution and changes that have occurred since the book's publication in 2004?

MD: It’s funny, because, in ways, that’s the big question I haven’t been able to answer for the last ten years. It’s hard to see something you love change, but at the same time, it’s foolish to pretend everything will stay the same. That conflict was part of the impetus for the original collection when I started conceptualizing it in 2000. I knew Montauk would change, and I wanted to capture some of the sentiment and beauty before it faded – specifically, I wanted to capture the way Montauk made me feel… And I didn’t want to be right here – ten years out from publication – being one of those sentimental, nostalgic people who whine and rant about change, you know? In that way, the collection achieves a lot of what I wanted it to – it freezes Montauk for those who want it frozen, and it lends some insights to those who don’t know what the hell their sentimental neighbors are ranting and whining about.

But I try not to deal in specifics, because I don’t think it’s necessarily an artist’s job to hold vigils (not that I don’t hold a bit of a personal candle for the East Deck and Salivar’s). I just know that I can’t really be objective, so I put the onus on my photographs to honor establishments or condemn developers… Does that make any sense?

SC: As a photographer, you have traveled and explored some of the most beautiful, interesting, and diverse places and locations around the world, but your love and loyalty for New York seems to always remain the same. What is it about New York, for those who many not understand, that lures you back and contributes to being your favorite place in the world?

MD: Well, I don’t think I could leave New York even if I wanted to… I grew up here. This has been my only real home, so you’re kind of adding the natural attraction that everyone feels to NY with the innate attachment that people have to the first place they’ve called home. It’s a tough spell to break.

At the same time, though, you could extrapolate my personal feelings on Montauk to the City, the State, and on and on… 2015 New York is certainly not the place where I grew up. Again, I’m not going to weep over the changes or organize a vigil – but it’s tough seeing your city loose the footholds that once nurtured artists and outsiders and the like. We’re hemorrhaging our creative class, and it’s scary to think that – if I were born today – I might be forced out to Detroit to pursue a career as a visual artist… I dunno… That’s a whole ‘nother conversation.

SC: When you first came up with the idea to publish your iconic book, The End: Montauk, NY, what was your main goal and what has been the most rewarding part of the journey?

MD: Like most of my work, The End: Montauk, N.Y. started as an attempt to build creative walls around a very particular, cloistered scene – its characters, its setting, its lifestyle, etc. – and then, from that, capture an idealized impression on that scene.

So, I didn’t want to be the documentarian that explains a foreign world, nor the insider bragging about his haunts, but rather a filmmaker, in a sense, who actually transports you to new environs, immerses you in a place and time, and tells a story in the process. At that point in time, when I was working on the collection, this type of narrative work wasn’t really being done in fine art – but I knew I couldn’t really do justice to Montauk – both as I knew it and imagined it – without approaching it as something with a plot…

As far as the rewards of the journey – the fact that I’m here reflecting on this work ten years later kind of says it all for me… I never thought The End would go out of print in two weeks, or generate the kind of demand that it has. I especially never thought it would ever become something on this scale – a large-format, signed numbered edition with prints and all that. It’s incredible.

It’s all been incredible, really – I’ve heard from thousands of people who respond to the work, and that’s a huge reward for me. This project was all about making material something that previously had existed in my mind as equal parts memory and reverie… It’s been tremendously meaningful to see so many people respond to the story, the characters and, moreover, the place – Montauk.

The next reward will come when I get to share this with people again… we’re doing some special events in the fall, and an Art Basel event, all leading up to the release of the 10th anniversary limited edition box set of The End. I think that’s when it will really sink in.

SC: Surfing is a main focus in your life and obviously in the book as well. What, in your opinion, differentiates surfing from other sports and activities? Do you think the city's energy and dichotomy between the beach and city life makes it especially different in New York?

MD: I’m not even sure if I can explain it, because it’s not even about the sport, but often what it represents – there’s escapism, balance, and a certain humility (before nature), or that need for adaptation… I don’t know many things in life that test a person – physically and spiritually – like surfing does. I mean, I’ll challenge any golfer who says his or her sport is a better metaphor…

Even as an artist, I’d be lying if I said my approach to my work hasn’t been inspired in some way by surfing. Trying to build a focused body of work – especially a narrative – that’s an endeavor that starts you off in some helpless, chaotic, and confusing places… I mean, you go out there with an idea, and you’re floating around, and you have to paddle and get up, or you’ll end up with a pile of shit… Maybe that’s not the best metaphor, but you get the idea. There’s not a huge margin of error in art, photography, filmmaking, and you have to get your timing and balance down…

As far as the second question – I can’t really compare the sport in NY to anywhere else. Maybe I’m too close to it. I grew up on Long Island, and now, I can see the Hudson from my place in Manhattan, so it’s just part of who I am. I grew up surfing and sailing and fishing. I’m most comfortable when I can stumble to the shore. I can’t imagine growing up on the coast and not feeling that way... I’d venture that that’s the same anywhere.

SC: Although Montauk and the East End has changed as time has progressed, there is undoubtedly still that sense of allure and untouched beauty about it. What are some of the things you still love most about this beach community?

MD: We’re talking about one of those places that just feels different, you know? You don’t have to tell a first-timer that they’re going somewhere special, because they can just get out of the car and feel it. And that’s still there. It’s something intangible – and for that matter ineffable. You can’t explain it, and you can’t erase it. That’s my Montauk: That’s what developers can’t destroy, and tourists can’t tread over… It’s a feeling that you get at Ditch Plains, or talking to a fisherman before a storm, or just staring out at the sea at sunrise. Something about the community, the natural beauty, the lifestyle… See, I can’t even finish my sentences… that’s the feeling.

And that’s the reason for the charitable component of the new book release. We’re giving a portion of the proceeds from each book to protect the ocean and those fragile shores, because of that feeling. If we lose that, we lose so much… How do you rebuild a feeling… something ineffable?

SC: What's up next for you in your career... We know you are working on your first feature film. Can you tell us a bit more about it?

MD: Sure… It’s a full-length doc following two years at The Riverhead Raceway - another endangered Long Island haunt that’s close to my heart. I did a 360-look at all aspects of the place – from the individuals who drive the beat-up old stock cars, to the commercial threats that will eventually shutter the track (which is Long Island's last). I grew up going to the track, so it’s a bit of a personal piece, but there’s also some of the same metaphor you might see in Montauk, or my work in Habana Libre… I’m making a case for endangered identity and underrepresented art… you know, as the shadows of strip malls creep into the frame. I like to describe it as “a David vs. Goliath story, only if David were a tow truck driver and Goliath were a Wal-Mart…”

I’m really excited about it. I did a whole series of abstract pieces that tie in with the film, so it’s kind of a real mixed media project too.

SC: If you could describe your perfect day, what would it consist of?

MD: Art would have to be one component of it… Probably what I call a “click day,” that one day during a project when all the ideas and hopes you have for something kind of click together, and you realize, “Hey, this thing might actually work!” (And I’m sure that happens in a surfer’s career, as much as it does an artist’s…) That’s what keeps so many of us going - when everything falls into place and you feel invincible. Maybe that breakthrough on a big project, followed by drinks and dinner with friends and family? Is that lame? Nevermind – Let’s go with trip to Mars, and dinner with Godard.

SC: You ran a very successful ad agency before you became a successful full-time photographer. What are some of the things that you are most appreciative of now that you can focus on your main passion?

MD: It was always about art. I was just lucky enough to realize – or re-realize – that when I did. I had some trepidation of course, but at the same time, I knew about Warhol and Irving Penn (both art directors in advertising), so I knew it wasn't an impossible jump to make. It's all about sensibilities and instincts. As an artist, you just get to treat those with more sincerity and let them come through as something raw and visceral.

Now, I mean, I appreciate it all. Being able, as I said before, to make real-world versions of ideas – and moreover to have those ideas reach people, and reach minds… That’s the beauty of art – a narrative about a small community of the East End may reach people in a way that an editorial on over-development can’t… I get to work in a medium that provokes and teaches in inexplicable ways. Like Whitman says (another Long Island guy, actually) “I and mine do not convince by arguments, similes, rhymes;/ We convince by our presence.” That, to me, is art.

The fact that I can be part of that… wow.

SC: Who have been some of the biggest professional and personal inspirations in your life?

MD: Again, without getting too specific, I’ll say, anyone (or thing) that’s resilient despite being repressed, adventurous despite being mortal, and creative despite being engineered solely to survive. That could be surfers in Montauk, or poets in Franco’s Spain… There’s no shortage of inspiration if you pay attention.

SC: Is there anywhere else in the world you would live?

MD: Again, I’ve always been interested in the way geography affects culture, and, moreover, how it creates exclusive groups. So I guess I have a running list with that criteria in mind: Africa, Asia, South America, Australia, Europe (again), and, why not, Antarctica.

The Usual Magazine interview with Michael Dweck

The Usual Magazine interview with Michael Dweck

When and how were you first drawn to photography?

I like to say that I was already a photographer before I even knew what photography was... My parents bought me my first camera when I was seven, and at that age, you don't really need to know the names of things to enjoy them or to investigate them. I would photograph on the beach by our house and play around with light and focus. I didn't know the word aperture or anything about lighting. I just knew that photographs looked great at a certain time of day, and that certain angles and actions of people resulted in something moving. There was something almost magical about photography and even the camera itself.

I'd later learn all about composition when I studied architecture then fine art, but at the heart of my passion was that time on the beach when I was discovering it for myself... Because that still informs what I do now more than anything I learned in a classroom or in a book – the magic of discovery.

You worked in advertising as a creative director for years before turning to photography full time. What was the job that pushed you to finally make the career shift?

I wouldn't say that it was the job, or any particular “job” therein that pushed me to shift careers... It was more of a sentiment. I started the company with an intention to do something I hadn't yet defined. After winning a Gold Lion at Cannes and landing a TV piece in the MoMA, I felt like things had defined themselves. And that was pretty much it.

That's the way I usually work – following instincts, rather than goals. Setting a goal keeps me in a maddening little container and sets me up for disappointment. Following a hunch – or some gut instinct – that allows me to explore and judge success in hindsight. And that's what I'm doing now, I guess. We'll see how it work out. [laughs.]

How hard was it to take that leap of faith and pursue your passion?

It was easy to decide, if difficult to execute. It's like deciding you want bouillabaisse for dinner. “Okay – done. I know what I want... now I just have to go to Gosman’s and buy all this seafood, and saffron and spend a couple hours prepping everything...” you know?

It was tough to disassemble that amazing world I built from the ground up and leave all those great people, but – I don't know – I just wanted bouillabaisse. [laughs.]

What qualities do you look for in your subjects?

Again, as with goals, I don't really search out subjects, per se I just happen to be surrounded by them no matter where I am in world – Montauk, NYC, Buenos Aires, Tokyo, Paris, Havana, Borneo [laughs] I think it’s just a matter of being open to find something without necessarily looking for it.

I always liken it to casting a film – something I'm kind of doing at the moment for my next project. If you go into the casting with a person in mind, you'll never be satisfied. If you go in, however, with an idea or a vibe in mind, you can find that in someone – even if he or she doesn't know it's there.

So my ideas or vibes are personal and just below the skin. I like expressive faces and figures still on the verge of knowing what they're expressing; youth that's in migration and struggling with urges, juggling confusion with sexuality.

I ultimately work in suggestion – that's almost my medium more than photography. And to maximize this, I find it best to work with people who have latent qualities that they haven't yet realized and/or exploited.

What is your process like gaining a subject's trust?

I don't know that I have one. I even don't know that I believe that a subject has to truly trust a photographer. When I meet someone I want to work with, I just introduce myself. I explain my work. That's pretty much it. We go from there.

As I said, I usually pick subjects based on naturally observed behavior, so it's not as if I have to woo them to present themselves in one manner or another. I just ask them to be themselves. And even if they're not – not comfortable or natural – that works sometimes too.

It’s a misconception that being a good model or subject is all about being attractive. Sure, that doesn’t hurt, but there has to be more… Complexity, curiosity, confidence, something below the surface that you can’t explain, but can capture in a photograph if you try hard enough.

What stories are you trying to tell through your photography?

It's very subtly hinted at, but all of my work is part of one grand arc about artificial intelligence and the impending technological singularity. [laughs.]

No, my work varies from project to project. With Montauk: The End, the narrative dealt with the idyllic space where youth and beauty are immortal and potential doesn't have an expiration date. Habana Libre had a long-form plot that followed a privileged class of people in a so-called “classless” society, with splinters of hope and potential in there too. Even Mermaids, which was my most abstract body of work, had a story built into its abstractions – a fantasy world below impressionistic waves. And in all of these there’s a recurring idea of suggestion... the interaction between subject and audience that plays out like some kind of elaborate dance. But that's more something elicited than told, I suppose.

You have seemingly endless imagery from Montauk. What is it about the town's people and places that you are so drawn to?

The village and the full-timers represent something beyond appearance – and that's what I love about them. More than any place I've ever lived, you guys understand what it means to be a community, to preserve identity and maintain hope in the face of the constant nonsense that swallows so much of their surroundings. It's a microcosm of the world, in a sense, but it's also a stark departure from it.

As an artist, what would you say are your greatest accomplishments thus far?

I think my most recent work, Habana Libre, was the most difficult and the most satisfying project I've undertaken. I mean, the fact that I was able to do endure eight separate trips to Cuba and come back with a project without getting arrested or falling in love is nothing short of a miracle to me. It required traveling to a location off-limits to most Americans, accessing a group of artists off-limits to most Cubans, and working in conditions too hot and festive for most sane adults. And then going back and becoming the first American contemporary artist to have a solo exhibition in a Cuban Museum – that was overwhelming to say the least.

But I might just be saying that because it’s my most recent project. Before that, I thought I’d never top Mermaids. I shot it mostly at night in the deep rivers of Florida, but it perfectly captured my feelings about the waters off Montauk and the barely-there sirens that call to me from below the surface as I’d fish late into the night.

The End:Montauk, N.Y. will always be a huge accomplishment too. That was my first real project, and one I sat on for years before I found the time to complete it. So, that means a lot for different reasons as well.

Do you have one photo you feel sums up Montauk?

I don't think any photograph can sum up anyplace – be it Montauk, Paris or The Sudan... It's the same with other art – I don't think a song can sum up surf culture, or a movie can sum up The Civil War. Art contributes to the understanding of things, places, people, events... but once artists claims to “explain” or “sum up” anything in whole, they're overstepping their bounds. That's just my opinion.

Do you follow photography trends or look to other photographers for inspiration?

I admire other photographers, for sure. That said, I don't really let their work inspire me necessarily. Maybe their work ethic or their legacies, but not their catalogs.

For inspiration, I look more to film and fine art – impressionist paintings, abstract sculpture, even architecture. I find so much great use of narrative, space and form in other mediums and I let those push the aesthetics of my work more than anything else.

In art, the pursuit of an idea is always more interesting than the conquest. Do you think this also applies to women and the key to what makes your images of women captivating?

I don't think the pursuit is always more interesting than the victory, or whatever... not in art or relationships. I think the former is just a different source of pleasure than the latter and I think it's important to differentiate those from one another. My work – especially in relation to women – deals with seduction or, as you called it, the pursuit phase. It's about insinuation and flirtation, where there's a very elegant and subtle undercurrent that keeps attentions intact. This, of course, strays quite a bit from “the conquest” which is carnal – and though often attractive in its own way – rarely subtle or contained. I try to stay in the wheelhouse – that place where seduction lives and desire has yet to knock.

Michael Dweck

Summer, 1975. I was seventeen and living with my family on Long Island when I heard the rumor that the Rolling Stones were recording an album at Andy Warhol’s place in Montauk. My friend Oscar and I packed up our instruments in his ‘71 Plymouth Valiant and headed for Montauk and, we were convinced, rock-and-roll history. We possessed the keys to a house belonging to the parents of someone my brother was dating and a belief in our own greatness completely disproportionate to our talents. We found the house at about two in the morning and immediately began playing as loud as we could with the doors and windows open. At this point, I might mention that our instruments were a slide trombone and a drum set. Needless to say, Mick, Keith, Charlie, and Ron didn’t take notice—but the neighbors sure did. We spent the next two days in an almost constant state of motion, driving from one end of the little fishing community to the next. While we never jammed with, or even saw the Stones (“You should have been here last night, they played for two hours right on that stage there,”) we did discover a place that seemed far removed from suburban civilian. The beaches were unspoiled, there was real surfing going on, and the girls looked, well, like they didn’t belong on Long Island.

I returned to Montauk many times, sometimes alone, sometimes with friends. More than once, I came with my parents. Always, I was the outsider. It wasn’t that the locals were mean (although some were). They just had a good thing going and they weren’t keen on sharing it with the whole world. Montauk was, and is, a fishing town that’s fighting to keep from becoming the next Hamptons, the next Fire Island, the next fill-in-the-blank. It’s 100 miles from Manhattan yet almost no one locks their doors and the taco stand extends credit. Everyone knows the freewheeling vibe can’t last; they’re just determined that it won’t disappear on their watch.

It was the desire to record something before it faded away that was the catalyst for this project. These images were supposed to chronicle one two-week period in the life of the town but it took me two weeks to realize I didn’t want to be constrained by any self-imposed rules (rules not being what Montauk is about). Two weeks turned into a summer. I focused on the subjects I was most interested in, the surfers. By and large, these are kids who are the same age I was when I first fell in love with the place. They are beautiful and sexy and tribal in a way no one who hasn’t been part of a surf community can understand. I can tell myself that I knew Montauk when it was better, when the beaches were less crowded and the summer crush could barely fill the two roadside motels. I can’t delude myself into thinking that I ever surfed as well, looked as good, or partied as hard as the young people who let me take their pictures. If the crew at Ditch were bitter over missing the Rolling Stones or Andy Warhol, they sure didn’t show it.

When I go to Montauk now, it’s often in the company of my wife and two children. My wife and daughter are already surfing and my son, I don’t doubt, will be graduating from his boogie board soon. What will the place look like when they’re old enough to chase a rock band or fall in love with someone they see peeling off a wetsuit in the parking lot? Now that I’ve been coming here long enough that I no longer worry about my car being vandalized if I surf at one of the hidden breaks, I don’t want any outsiders arriving with notions of building big houses, opening a real hotel or, heaven forbid, paving any more roads. I don’t want anyone coming to Montauk who I don’t know. Period.

It’s always been my hope that the men and women who let me take their pictures see this book and think that I’ve paid them and their town a high compliment. But if my book, even in some small way, hastens the demise of the lifestyle it seeks to glorify, then I’ve shot myself in the foot. It’s taken me 28 years just to get some of the residents of Montauk to say hello to me. If they believe that I’ve brought the whole world down on them, I’ll have to start parking under streetlights again. And there are damn few streetlights in Montauk.

That’s the way it always goes, isn’t it? Everyone who makes it to the fallout shelter tries to bolt the door behind him. It’s like some graffiti I read in the stall at the Shagwong Tavern. “Welcome to Montauk. Take a picture and get the f--- out.”

Here are my pictures. Please, please stay away just a little longer.

Rusty Drumm

From the vantage of the 2002 wave-crowded summer season, it's difficult to recall the pure, undiluted stoke that we who pioneered surfing in Montauk felt in the 1960s.

The waves here were far better than those we had known to the west on Long Island, although a few of us were lucky enough to have experienced Hawaiian and Californian juice. The stoke had to do with the waves, yes, but it was much more about the untrammeled nature that surrounded us on land and in the waves.

We take for granted a truth that, though shared with other places in the country, is truer on Long Island. The truth is that people are like seals. When too many of them have to share the same rock, a number of them move away. On Long Island, the path of flight is west-to-east away from New York City. I make this observation in order to explain why Montauk, on the very end of the South Fork of Long Island, 120 (which is correct? you say 100 in your essay) miles east of Manhattan, was considered remote even back in the 1960s. Simply put, claustrophobic people did not have to travel so far in 1965 to escape their panic, and the roads of escape were not as straight.

For those of us who were in our late teens, early 20s, Montauk was like the lost world. We camped where we wanted to, built roaring beach fires, drank beer, smoked nature, and surfed waves with nobody else on them. This was long before the saloons were gentrified. The Shagwong Tavern was a fishermen’s bar, like all the others, with pool tables, fish mounts on their walls, and photos of big sharks and tuna, as well as the captains and anglers that have made Montauk the "Fishing capitol of the World." Fitzgeralds down on the docks still had spitoons on the floor. Frank Mundus, the "Monster Man," was in his heyday, the nails of his big toes painted green and red for port and starboard, bringing gigantic white sharks back from offshore.

Many of us tented in the Ditch Plains trailer park for something like $25 a week. Allan Weisbecker had a waterbed outside his tent that heated up during the day, perfect for when the sun went down. Roland Eisenberg and I lived in a cabin we called "Casa Non-Movita" because it sat next to a trailer named the "Casa Movita." Sam Slomon, an interior decorator from the city, had a trailer plot he called "Samalot," where he entertained surfers and their girlfriends, feeding us well, and performing Swan Lake or the Dance of the Seven Veils after dinner. You had to be there. I remember my ensemble at one of Sam's very late night soirées consisted of a wetsuit, dinner jacket, and top hat. You get the picture. Michael Cochran was a "pearl diver," that is, a dishwasher at a local restaurant. We worked in restaurants, bars, for contractors, and those of us who had begun (without knowing it) lifelong careers as commercial fishermen by clamming back west, got jobs crewing on fishing boats.

The jobs supported our habit, which was surfing, and Montauk's unique geology supported the surf. Unlike most of the East Coast, Montauk's surf breaks on rock reefs, and the swells come out of deep water, unslowed by the drag of gradual slope of sand banks. Spots like Turtle Cove, The Ranch, Cavett's Cove, and Air Force Base, produce world-class waves when visited by swells generated by tropical storms. We knew when the swell hit in the night because Montauk's morainal boulders and cobblestones would begin to growl as the pull and push of a distant storm moved them about.

A few surfers were already here. The late Bob Akin, his brother Bill, Bob Aaron, who just died, Gene DePasquale and his young sons. The rest of us made our way slowly, making jobs where none existed in order to stay in close proximity to Montauk’s waves and overall beauty. We have passed surf fever on to our kids—a new tribe of young surf rats claiming its own section of beach each year. We put up with the hordes that make their summer migration to our home knowing that in early spring and late fall, when hurricane swells make secret spots come alive, we will be reunited with the dream that brought us here in the fist place.

The End: Montauk, N.Y.. Art Edition 'Surf’s Up’, 2016

The End: Montauk, NY

By Michael Dweck

Art Edition limited to 100 numbered copies - clothbound book (256 pages) packaged in clothbound clamshell box, each signed by Michael Dweck, includes the gelatin silver print “Surf's Up” (Montauk, 2006) – format: 35.5 x 28 cm (14 x 11 in.).

The limited edition printing – originally hailed as “the ultimate homage to the sun-kissed surfing life…” – will feature 85 previously unpublished photos, and a reflective essay by Dweck.

Originally published in 2004, The End presented an idyllic and erotic portrait of the famed Long Island, NY, fishing community, and offered an idealized glimpse into the lives of the beautiful denizens who comprised its surfing subculture. From the dunes of Montauk’s secret surfing haunts, Dweck’s first major photographic work told a paradisiacal narrative about summer and youth, which blended idealism and documentation to reflect a place and a way of life both fading and being reinvented. The original run, as the New York Times noted, “sold out its first printing of 5,000 books in less than three weeks,” and became an instant classic, fueled by its groundbreaking narrative form, and now-iconic images like the cover’s nude, “Sonya”, “Dave and Pam in their Caddy”, “Adriana” and “Lilla.”Collectors of fine art photography will relish this rare opportunity to own a signed, numbered, limited edition volume – as well as the gelatin silver print of one of his photographs.

The expanded 10th Anniversary Art Edition Box Set of The End: Montauk, N.Y. (limited edition of 300) examines the legacy of this original work, but also addresses the myriad of changes Dweck predicted when he first turned his camera to Montauk in early 2000.

Printed in Italy, each copy will be signed and numbered, and packaged in a handmade, cloth-lined clamshell case, with an exclusive 11x14 silver gelatin print, also signed and numbered.

A portion of the proceeds from the sale of The End: Montauk, N.Y. will go towards maintaining the waterways and beaches of Long Island and the U.S. through the Surfrider Foundation and Operation Splash.

Also available in two other Art Editions (No. 101-200, 201-300) each with alternate silver gelatin photographs signed by Michael Dweck.

Michael Dweck

The End: Montauk, N.Y.

by Christopher Sweet

Michael Dweck’s first major photographic work was published in volume form as The End: Montauk, N.Y., in 2004, and was featured in several exhibitions and art fairs that year. The work portrays the old fishing community of Montauk and its surfing subculture. It is an evocation of a real-world paradise lost: the paradise of summer, youth, and erotic possibility — an American version of the Arcadian vision. Blending nostalgia, fantasy, and documentation the photographs present a compelling portrait of a place in time and a way of life at once fading and being reinvented with each new season.

The signature photograph of the collection, Sonya, Poles, is an image of ecstaticsummer. A beautiful young woman in full naked glory — her blond hair blown back, her breasts aloft, a smile of anticipation — bounds across a glistening beach, a surfboard under her arm, toward the incoming waves. In the far distance — in the upper margin of the picture — waves and dunes, surf and scrub fringe the horizon line which divides her head from her body. Her face is profiled against the great sky, and her dynamic body against the flat expanse of wet sand. All the bliss of summer fun and youthful promise is summed up by her scissor kick, reiterated by her shadow and her reflection, a vivacious “v” form that becomes a faceted diamond cleaved from light. And that bolt of white, her surfboard, like a missile, will carve out the place on the wave that will bear her back over the beating tide like a goddess from the sea.

A tattered Old Glory flaps in the wind, an abandoned VW camper sits near theside of the road, beached like a dead whale, its former glory as a Love Bug long lost. Cars pull up in the parking lot near the beach. People slip out of their t-shirts and jeans and into bathing suits. The gear is unloaded. The tribe gathers. Aging sybarites ponder their past glories while oblivious, feckless youth in full flower frolics on the beach, cavorts in the water, sits out on the gentle swells waiting for waves, or makes mischief up at the motel or back at the cottage. Old timers measure the days, the years not by how far they have come, but how close they have remained and yet how much the place and they have changed, how much the weeds have grown up around them like the abandoned camper. An old surfboard, left under a house some twenty, thirty years before finds its original owner just down the road. At night the luau begins and the girls in grass skirts tease the men and boys. And the pleasures of the night beckon.

A few old timers show up, hang out, nowhere else to go, not part of the party butregulars on the scene. They add a little texture, lend a bit of character – like relics and artifacts – and are tolerated, at times perhaps indulged, as long as they don’t bother the girls. They serve as reminders that the past is not just the sound of receding trumpets. The years roll on like the tides, the seasons turn, and each summer brings its own story. With each new year, there is some new development, new blood, and more and more the hazard of new fortunes changing the balance and tone. New arrivals take it as they find it. Only the lifers, of one sort or another, bear the burden of how things ought to be, how things used to be.

Michael Dweck’s The End: Montauk, N.Y., is a private Idaho, a personal Eden, atonce remembered and imagined. The Arcadian setting is a place for recreation, self-invention, and the celebration of physical beauty and well-being and the tender temptations of the flesh. It is a down-home beach paradise of a distinctly American variety, Endless Summer, that blessed but all too brief interlude that separates the seasons of school and work, adolescence and adulthood. Dweck’s vision of the far end of the island mingles the yearnings and anxieties of youth and age, of callowness and conscience, the exuberance of one’s salad days and the frisson of old bachelors. The season in the sun in due course passes into autumn. Youth and beauty blush, exude their sweetness, exert their power, but inevitably falter and fade before the onslaught of the years under the overarching, ozone-depleted sky. Our times are not in our hands. The eviction notice is tied to the gate, even as one enters, and the unease of that knowledge hovers over the good fun. The golden youth of one summer is the worldly-wise veteran or the broken old timer of another. The End is an elegy to the evanescence of youth and an ode to the consolation of art.

Art Edition A, No. 1–100

- The End: Montauk, N.Y. 2015 by Michael Dweck

- Essays by Michael Dweck and others

- Published by Ditch Plains Press

- Large format hardcover: 27.94 x 35.56 cm (11 x 14 in.) with 256 pages, 260 duotone plates, 15 color-plates and 3 gatefolds

- Limited to 100 copies

- Each book numbered and signed by Michael Dweck

- Includes a gelatin silver print "Surf’s Up", Montauk 2006, signed and numbered by Michael Dweck

- Release date: 2016

- Printed and bound in Italy

- ISBN 978-0-9818465-1-4

- Oversize clothbound clamshell box 31.7 x 39.4 x 5.7 cm. (12.5 x 15.5 x 2.25 in.)

The duotone illustrations are made with a special treatment for black and white images that produces exquisite tonal range and density. All color illustrations are color-separated and reproduced in the finest technique available today, which provides unequalled intensity and color range.

About Michael Dweck

Michael Dweck is an American photographer, filmmaker and visual artist.

His work has been featured in solo exhibitions around the world, and become part of important international art collections. Notable solo exhibitions include Montauk: The End, 2004, a paradisiacal and erotic surf narrative set on Long Island; Mermaids, 2009, which explored the female nude refracted by river waters; and Habana Libre, 2010; an intimate exploration of privileged artists in socialist Cuba, which made him the first living American artist to have a solo exhibition in Cuba. These and other works have also been published in large, limited-edition volumes.

Previously, Dweck studied fine arts at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York and went on to become a highly regarded Creative Director, receiving more than 40 international awards, including the coveted Gold Lion at the Cannes International Festival in France. Two of his long-form television pieces are part of the permanent film collection of The Museum of Modern Art in New York. Michael Dweck currently lives in New York City and Montauk, N.Y., where he is finishing his first feature-length film.

“the ultimate homage to the sun-kissed surfing life…”

– New York Times

Flag at Snug Harbor, Montauk 2002

Flag at Snug Harbor, Montauk 2002  Adriana at The Panoramic View, Montauk 2002

Adriana at The Panoramic View, Montauk 2002  Surf’s Up, Montauk 2006

Surf’s Up, Montauk 2006  Lilla, Nappeague 2002

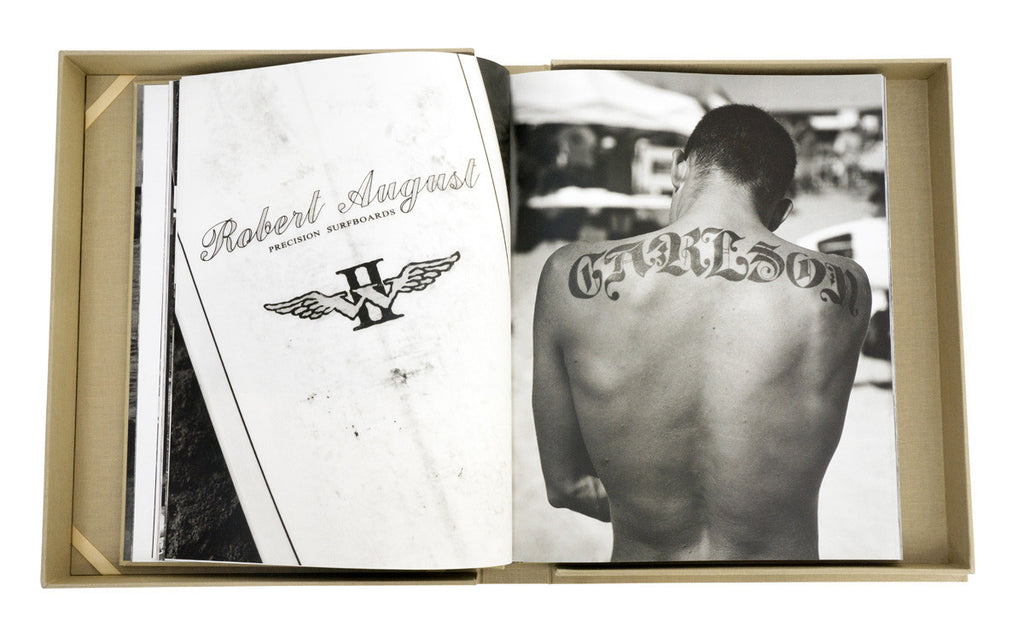

Lilla, Nappeague 2002  Old Boards at Tony’s House

Old Boards at Tony’s House  Surfing at Ditch Plains, Montauk 2002

Surfing at Ditch Plains, Montauk 2002  Ray, Montauk 2002

Ray, Montauk 2002  Morning surf at Poles, Montauk 2012

Morning surf at Poles, Montauk 2012  Jessica and Kurt, Montauk 2002

Jessica and Kurt, Montauk 2002  Getting wet, Cavett’s Cove Montauk 2006

Getting wet, Cavett’s Cove Montauk 2006  Laying out, Montauk 2012

Laying out, Montauk 2012  Lilla, Nappeague 2002

Lilla, Nappeague 2002  Wave after the storm, Montauk 2009

Wave after the storm, Montauk 2009  Cooling off, Turtle Cove, Montauk 2012

Cooling off, Turtle Cove, Montauk 2012  Julia and Brittany, Hither Hills/Apres surf, Montauk 2012

Julia and Brittany, Hither Hills/Apres surf, Montauk 2012  Lilla, Nappeague 2002

Lilla, Nappeague 2002  Natalie on the Rocks, Camp Hero, Montauk 2008

Natalie on the Rocks, Camp Hero, Montauk 2008  Surfing Air Force Base, Montauk 2013

Surfing Air Force Base, Montauk 2013  Calm Before the Storm, Montauk 2008

Calm Before the Storm, Montauk 2008  Poster from the Sotheby’s exhibition 2003

Poster from the Sotheby’s exhibition 2003  Sotheby’s exhibition 2003

Sotheby’s exhibition 2003  Sotheby’s exhibition 2003

Sotheby’s exhibition 2003  Sotheby’s exhibition installation 2003

Sotheby’s exhibition installation 2003  Sotheby’s exhibition 2003

Sotheby’s exhibition 2003  Staley Wise exhibition 2012

Staley Wise exhibition 2012  Staley Wise exhibition 2012

Staley Wise exhibition 2012

Michael Dweck The End: Montauk, N.Y

In the 1960s, the fishing village of Montauk became the surfer's paradise of the United States' East Coast. Located as the tip of Long Island's South Fork, the easternmost point of the Hamptons, this paradise existed primarily for locals - not surfers who migrated to the beach for the summer, but those who were out in the rocky reefs every day, year round. Today, a new tribe of surfers exists - a group of young locals who live by their own rules. Rule number 1: Never tell anyone where the good surf spots are. Rule number 2: See rule number 1. In the 1990s, photographer Michael Dweck rented a house on Ditch Plains beach (site of the best surf break) and struck up a friendship with one of the local surfers, eventually gaining uprecedented access to the insular local surf community. Dweck's photographic essay follows the surfers through their daily rituals, from early morning wave reports to evening bonfires on the beach, capturing their youthful hedonism. Through portraits, nudes, and photographs of the landscape, this book celebrates lives lived only to surf, and captures an endless summer of perfect weather and languorous beauty.

Surf Collective Interview with Michael Dweck

Surf Collective

Interview with Michael Dweck

SC: You are a true native and longtime resident of Long Island. You've seen it evolve and change in many ways, especially around Montauk and the areas you pay tribute to in the book. What are your thoughts on the evolution and changes that have occurred since the book's publication in 2004?

MD: It’s funny, because, in ways, that’s the big question I haven’t been able to answer for the last ten years. It’s hard to see something you love change, but at the same time, it’s foolish to pretend everything will stay the same. That conflict was part of the impetus for the original collection when I started conceptualizing it in 2000. I knew Montauk would change, and I wanted to capture some of the sentiment and beauty before it faded – specifically, I wanted to capture the way Montauk made me feel… And I didn’t want to be right here – ten years out from publication – being one of those sentimental, nostalgic people who whine and rant about change, you know? In that way, the collection achieves a lot of what I wanted it to – it freezes Montauk for those who want it frozen, and it lends some insights to those who don’t know what the hell their sentimental neighbors are ranting and whining about.

But I try not to deal in specifics, because I don’t think it’s necessarily an artist’s job to hold vigils (not that I don’t hold a bit of a personal candle for the East Deck and Salivar’s). I just know that I can’t really be objective, so I put the onus on my photographs to honor establishments or condemn developers… Does that make any sense?

SC: As a photographer, you have traveled and explored some of the most beautiful, interesting, and diverse places and locations around the world, but your love and loyalty for New York seems to always remain the same. What is it about New York, for those who many not understand, that lures you back and contributes to being your favorite place in the world?

MD: Well, I don’t think I could leave New York even if I wanted to… I grew up here. This has been my only real home, so you’re kind of adding the natural attraction that everyone feels to NY with the innate attachment that people have to the first place they’ve called home. It’s a tough spell to break.

At the same time, though, you could extrapolate my personal feelings on Montauk to the City, the State, and on and on… 2015 New York is certainly not the place where I grew up. Again, I’m not going to weep over the changes or organize a vigil – but it’s tough seeing your city loose the footholds that once nurtured artists and outsiders and the like. We’re hemorrhaging our creative class, and it’s scary to think that – if I were born today – I might be forced out to Detroit to pursue a career as a visual artist… I dunno… That’s a whole ‘nother conversation.

SC: When you first came up with the idea to publish your iconic book, The End: Montauk, NY, what was your main goal and what has been the most rewarding part of the journey?

MD: Like most of my work, The End: Montauk, N.Y. started as an attempt to build creative walls around a very particular, cloistered scene – its characters, its setting, its lifestyle, etc. – and then, from that, capture an idealized impression on that scene.

So, I didn’t want to be the documentarian that explains a foreign world, nor the insider bragging about his haunts, but rather a filmmaker, in a sense, who actually transports you to new environs, immerses you in a place and time, and tells a story in the process. At that point in time, when I was working on the collection, this type of narrative work wasn’t really being done in fine art – but I knew I couldn’t really do justice to Montauk – both as I knew it and imagined it – without approaching it as something with a plot…

As far as the rewards of the journey – the fact that I’m here reflecting on this work ten years later kind of says it all for me… I never thought The End would go out of print in two weeks, or generate the kind of demand that it has. I especially never thought it would ever become something on this scale – a large-format, signed numbered edition with prints and all that. It’s incredible.

It’s all been incredible, really – I’ve heard from thousands of people who respond to the work, and that’s a huge reward for me. This project was all about making material something that previously had existed in my mind as equal parts memory and reverie… It’s been tremendously meaningful to see so many people respond to the story, the characters and, moreover, the place – Montauk.

The next reward will come when I get to share this with people again… we’re doing some special events in the fall, and an Art Basel event, all leading up to the release of the 10th anniversary limited edition box set of The End. I think that’s when it will really sink in.

SC: Surfing is a main focus in your life and obviously in the book as well. What, in your opinion, differentiates surfing from other sports and activities? Do you think the city's energy and dichotomy between the beach and city life makes it especially different in New York?

MD: I’m not even sure if I can explain it, because it’s not even about the sport, but often what it represents – there’s escapism, balance, and a certain humility (before nature), or that need for adaptation… I don’t know many things in life that test a person – physically and spiritually – like surfing does. I mean, I’ll challenge any golfer who says his or her sport is a better metaphor…

Even as an artist, I’d be lying if I said my approach to my work hasn’t been inspired in some way by surfing. Trying to build a focused body of work – especially a narrative – that’s an endeavor that starts you off in some helpless, chaotic, and confusing places… I mean, you go out there with an idea, and you’re floating around, and you have to paddle and get up, or you’ll end up with a pile of shit… Maybe that’s not the best metaphor, but you get the idea. There’s not a huge margin of error in art, photography, filmmaking, and you have to get your timing and balance down…

As far as the second question – I can’t really compare the sport in NY to anywhere else. Maybe I’m too close to it. I grew up on Long Island, and now, I can see the Hudson from my place in Manhattan, so it’s just part of who I am. I grew up surfing and sailing and fishing. I’m most comfortable when I can stumble to the shore. I can’t imagine growing up on the coast and not feeling that way... I’d venture that that’s the same anywhere.

SC: Although Montauk and the East End has changed as time has progressed, there is undoubtedly still that sense of allure and untouched beauty about it. What are some of the things you still love most about this beach community?

MD: We’re talking about one of those places that just feels different, you know? You don’t have to tell a first-timer that they’re going somewhere special, because they can just get out of the car and feel it. And that’s still there. It’s something intangible – and for that matter ineffable. You can’t explain it, and you can’t erase it. That’s my Montauk: That’s what developers can’t destroy, and tourists can’t tread over… It’s a feeling that you get at Ditch Plains, or talking to a fisherman before a storm, or just staring out at the sea at sunrise. Something about the community, the natural beauty, the lifestyle… See, I can’t even finish my sentences… that’s the feeling.

And that’s the reason for the charitable component of the new book release. We’re giving a portion of the proceeds from each book to protect the ocean and those fragile shores, because of that feeling. If we lose that, we lose so much… How do you rebuild a feeling… something ineffable?

SC: What's up next for you in your career... We know you are working on your first feature film. Can you tell us a bit more about it?

MD: Sure… It’s a full-length doc following two years at The Riverhead Raceway - another endangered Long Island haunt that’s close to my heart. I did a 360-look at all aspects of the place – from the individuals who drive the beat-up old stock cars, to the commercial threats that will eventually shutter the track (which is Long Island's last). I grew up going to the track, so it’s a bit of a personal piece, but there’s also some of the same metaphor you might see in Montauk, or my work in Habana Libre… I’m making a case for endangered identity and underrepresented art… you know, as the shadows of strip malls creep into the frame. I like to describe it as “a David vs. Goliath story, only if David were a tow truck driver and Goliath were a Wal-Mart…”

I’m really excited about it. I did a whole series of abstract pieces that tie in with the film, so it’s kind of a real mixed media project too.

SC: If you could describe your perfect day, what would it consist of?

MD: Art would have to be one component of it… Probably what I call a “click day,” that one day during a project when all the ideas and hopes you have for something kind of click together, and you realize, “Hey, this thing might actually work!” (And I’m sure that happens in a surfer’s career, as much as it does an artist’s…) That’s what keeps so many of us going - when everything falls into place and you feel invincible. Maybe that breakthrough on a big project, followed by drinks and dinner with friends and family? Is that lame? Nevermind – Let’s go with trip to Mars, and dinner with Godard.

SC: You ran a very successful ad agency before you became a successful full-time photographer. What are some of the things that you are most appreciative of now that you can focus on your main passion?

MD: It was always about art. I was just lucky enough to realize – or re-realize – that when I did. I had some trepidation of course, but at the same time, I knew about Warhol and Irving Penn (both art directors in advertising), so I knew it wasn't an impossible jump to make. It's all about sensibilities and instincts. As an artist, you just get to treat those with more sincerity and let them come through as something raw and visceral.

Now, I mean, I appreciate it all. Being able, as I said before, to make real-world versions of ideas – and moreover to have those ideas reach people, and reach minds… That’s the beauty of art – a narrative about a small community of the East End may reach people in a way that an editorial on over-development can’t… I get to work in a medium that provokes and teaches in inexplicable ways. Like Whitman says (another Long Island guy, actually) “I and mine do not convince by arguments, similes, rhymes;/ We convince by our presence.” That, to me, is art.

The fact that I can be part of that… wow.

SC: Who have been some of the biggest professional and personal inspirations in your life?

MD: Again, without getting too specific, I’ll say, anyone (or thing) that’s resilient despite being repressed, adventurous despite being mortal, and creative despite being engineered solely to survive. That could be surfers in Montauk, or poets in Franco’s Spain… There’s no shortage of inspiration if you pay attention.

SC: Is there anywhere else in the world you would live?

MD: Again, I’ve always been interested in the way geography affects culture, and, moreover, how it creates exclusive groups. So I guess I have a running list with that criteria in mind: Africa, Asia, South America, Australia, Europe (again), and, why not, Antarctica.

The Usual Magazine interview with Michael Dweck

The Usual Magazine interview with Michael Dweck

When and how were you first drawn to photography?

I like to say that I was already a photographer before I even knew what photography was... My parents bought me my first camera when I was seven, and at that age, you don't really need to know the names of things to enjoy them or to investigate them. I would photograph on the beach by our house and play around with light and focus. I didn't know the word aperture or anything about lighting. I just knew that photographs looked great at a certain time of day, and that certain angles and actions of people resulted in something moving. There was something almost magical about photography and even the camera itself.

I'd later learn all about composition when I studied architecture then fine art, but at the heart of my passion was that time on the beach when I was discovering it for myself... Because that still informs what I do now more than anything I learned in a classroom or in a book – the magic of discovery.

You worked in advertising as a creative director for years before turning to photography full time. What was the job that pushed you to finally make the career shift?

I wouldn't say that it was the job, or any particular “job” therein that pushed me to shift careers... It was more of a sentiment. I started the company with an intention to do something I hadn't yet defined. After winning a Gold Lion at Cannes and landing a TV piece in the MoMA, I felt like things had defined themselves. And that was pretty much it.

That's the way I usually work – following instincts, rather than goals. Setting a goal keeps me in a maddening little container and sets me up for disappointment. Following a hunch – or some gut instinct – that allows me to explore and judge success in hindsight. And that's what I'm doing now, I guess. We'll see how it work out. [laughs.]

How hard was it to take that leap of faith and pursue your passion?

It was easy to decide, if difficult to execute. It's like deciding you want bouillabaisse for dinner. “Okay – done. I know what I want... now I just have to go to Gosman’s and buy all this seafood, and saffron and spend a couple hours prepping everything...” you know?

It was tough to disassemble that amazing world I built from the ground up and leave all those great people, but – I don't know – I just wanted bouillabaisse. [laughs.]

What qualities do you look for in your subjects?

Again, as with goals, I don't really search out subjects, per se I just happen to be surrounded by them no matter where I am in world – Montauk, NYC, Buenos Aires, Tokyo, Paris, Havana, Borneo [laughs] I think it’s just a matter of being open to find something without necessarily looking for it.

I always liken it to casting a film – something I'm kind of doing at the moment for my next project. If you go into the casting with a person in mind, you'll never be satisfied. If you go in, however, with an idea or a vibe in mind, you can find that in someone – even if he or she doesn't know it's there.

So my ideas or vibes are personal and just below the skin. I like expressive faces and figures still on the verge of knowing what they're expressing; youth that's in migration and struggling with urges, juggling confusion with sexuality.

I ultimately work in suggestion – that's almost my medium more than photography. And to maximize this, I find it best to work with people who have latent qualities that they haven't yet realized and/or exploited.

What is your process like gaining a subject's trust?

I don't know that I have one. I even don't know that I believe that a subject has to truly trust a photographer. When I meet someone I want to work with, I just introduce myself. I explain my work. That's pretty much it. We go from there.

As I said, I usually pick subjects based on naturally observed behavior, so it's not as if I have to woo them to present themselves in one manner or another. I just ask them to be themselves. And even if they're not – not comfortable or natural – that works sometimes too.

It’s a misconception that being a good model or subject is all about being attractive. Sure, that doesn’t hurt, but there has to be more… Complexity, curiosity, confidence, something below the surface that you can’t explain, but can capture in a photograph if you try hard enough.

What stories are you trying to tell through your photography?

It's very subtly hinted at, but all of my work is part of one grand arc about artificial intelligence and the impending technological singularity. [laughs.]

No, my work varies from project to project. With Montauk: The End, the narrative dealt with the idyllic space where youth and beauty are immortal and potential doesn't have an expiration date. Habana Libre had a long-form plot that followed a privileged class of people in a so-called “classless” society, with splinters of hope and potential in there too. Even Mermaids, which was my most abstract body of work, had a story built into its abstractions – a fantasy world below impressionistic waves. And in all of these there’s a recurring idea of suggestion... the interaction between subject and audience that plays out like some kind of elaborate dance. But that's more something elicited than told, I suppose.

You have seemingly endless imagery from Montauk. What is it about the town's people and places that you are so drawn to?

The village and the full-timers represent something beyond appearance – and that's what I love about them. More than any place I've ever lived, you guys understand what it means to be a community, to preserve identity and maintain hope in the face of the constant nonsense that swallows so much of their surroundings. It's a microcosm of the world, in a sense, but it's also a stark departure from it.

As an artist, what would you say are your greatest accomplishments thus far?

I think my most recent work, Habana Libre, was the most difficult and the most satisfying project I've undertaken. I mean, the fact that I was able to do endure eight separate trips to Cuba and come back with a project without getting arrested or falling in love is nothing short of a miracle to me. It required traveling to a location off-limits to most Americans, accessing a group of artists off-limits to most Cubans, and working in conditions too hot and festive for most sane adults. And then going back and becoming the first American contemporary artist to have a solo exhibition in a Cuban Museum – that was overwhelming to say the least.

But I might just be saying that because it’s my most recent project. Before that, I thought I’d never top Mermaids. I shot it mostly at night in the deep rivers of Florida, but it perfectly captured my feelings about the waters off Montauk and the barely-there sirens that call to me from below the surface as I’d fish late into the night.

The End:Montauk, N.Y. will always be a huge accomplishment too. That was my first real project, and one I sat on for years before I found the time to complete it. So, that means a lot for different reasons as well.

Do you have one photo you feel sums up Montauk?

I don't think any photograph can sum up anyplace – be it Montauk, Paris or The Sudan... It's the same with other art – I don't think a song can sum up surf culture, or a movie can sum up The Civil War. Art contributes to the understanding of things, places, people, events... but once artists claims to “explain” or “sum up” anything in whole, they're overstepping their bounds. That's just my opinion.

Do you follow photography trends or look to other photographers for inspiration?

I admire other photographers, for sure. That said, I don't really let their work inspire me necessarily. Maybe their work ethic or their legacies, but not their catalogs.

For inspiration, I look more to film and fine art – impressionist paintings, abstract sculpture, even architecture. I find so much great use of narrative, space and form in other mediums and I let those push the aesthetics of my work more than anything else.

In art, the pursuit of an idea is always more interesting than the conquest. Do you think this also applies to women and the key to what makes your images of women captivating?

I don't think the pursuit is always more interesting than the victory, or whatever... not in art or relationships. I think the former is just a different source of pleasure than the latter and I think it's important to differentiate those from one another. My work – especially in relation to women – deals with seduction or, as you called it, the pursuit phase. It's about insinuation and flirtation, where there's a very elegant and subtle undercurrent that keeps attentions intact. This, of course, strays quite a bit from “the conquest” which is carnal – and though often attractive in its own way – rarely subtle or contained. I try to stay in the wheelhouse – that place where seduction lives and desire has yet to knock.

Michael Dweck

Summer, 1975. I was seventeen and living with my family on Long Island when I heard the rumor that the Rolling Stones were recording an album at Andy Warhol’s place in Montauk. My friend Oscar and I packed up our instruments in his ‘71 Plymouth Valiant and headed for Montauk and, we were convinced, rock-and-roll history. We possessed the keys to a house belonging to the parents of someone my brother was dating and a belief in our own greatness completely disproportionate to our talents. We found the house at about two in the morning and immediately began playing as loud as we could with the doors and windows open. At this point, I might mention that our instruments were a slide trombone and a drum set. Needless to say, Mick, Keith, Charlie, and Ron didn’t take notice—but the neighbors sure did. We spent the next two days in an almost constant state of motion, driving from one end of the little fishing community to the next. While we never jammed with, or even saw the Stones (“You should have been here last night, they played for two hours right on that stage there,”) we did discover a place that seemed far removed from suburban civilian. The beaches were unspoiled, there was real surfing going on, and the girls looked, well, like they didn’t belong on Long Island.

I returned to Montauk many times, sometimes alone, sometimes with friends. More than once, I came with my parents. Always, I was the outsider. It wasn’t that the locals were mean (although some were). They just had a good thing going and they weren’t keen on sharing it with the whole world. Montauk was, and is, a fishing town that’s fighting to keep from becoming the next Hamptons, the next Fire Island, the next fill-in-the-blank. It’s 100 miles from Manhattan yet almost no one locks their doors and the taco stand extends credit. Everyone knows the freewheeling vibe can’t last; they’re just determined that it won’t disappear on their watch.

It was the desire to record something before it faded away that was the catalyst for this project. These images were supposed to chronicle one two-week period in the life of the town but it took me two weeks to realize I didn’t want to be constrained by any self-imposed rules (rules not being what Montauk is about). Two weeks turned into a summer. I focused on the subjects I was most interested in, the surfers. By and large, these are kids who are the same age I was when I first fell in love with the place. They are beautiful and sexy and tribal in a way no one who hasn’t been part of a surf community can understand. I can tell myself that I knew Montauk when it was better, when the beaches were less crowded and the summer crush could barely fill the two roadside motels. I can’t delude myself into thinking that I ever surfed as well, looked as good, or partied as hard as the young people who let me take their pictures. If the crew at Ditch were bitter over missing the Rolling Stones or Andy Warhol, they sure didn’t show it.

When I go to Montauk now, it’s often in the company of my wife and two children. My wife and daughter are already surfing and my son, I don’t doubt, will be graduating from his boogie board soon. What will the place look like when they’re old enough to chase a rock band or fall in love with someone they see peeling off a wetsuit in the parking lot? Now that I’ve been coming here long enough that I no longer worry about my car being vandalized if I surf at one of the hidden breaks, I don’t want any outsiders arriving with notions of building big houses, opening a real hotel or, heaven forbid, paving any more roads. I don’t want anyone coming to Montauk who I don’t know. Period.

It’s always been my hope that the men and women who let me take their pictures see this book and think that I’ve paid them and their town a high compliment. But if my book, even in some small way, hastens the demise of the lifestyle it seeks to glorify, then I’ve shot myself in the foot. It’s taken me 28 years just to get some of the residents of Montauk to say hello to me. If they believe that I’ve brought the whole world down on them, I’ll have to start parking under streetlights again. And there are damn few streetlights in Montauk.

That’s the way it always goes, isn’t it? Everyone who makes it to the fallout shelter tries to bolt the door behind him. It’s like some graffiti I read in the stall at the Shagwong Tavern. “Welcome to Montauk. Take a picture and get the f--- out.”

Here are my pictures. Please, please stay away just a little longer.

Rusty Drumm

From the vantage of the 2002 wave-crowded summer season, it's difficult to recall the pure, undiluted stoke that we who pioneered surfing in Montauk felt in the 1960s.