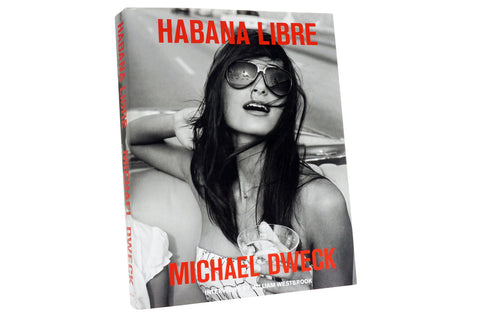

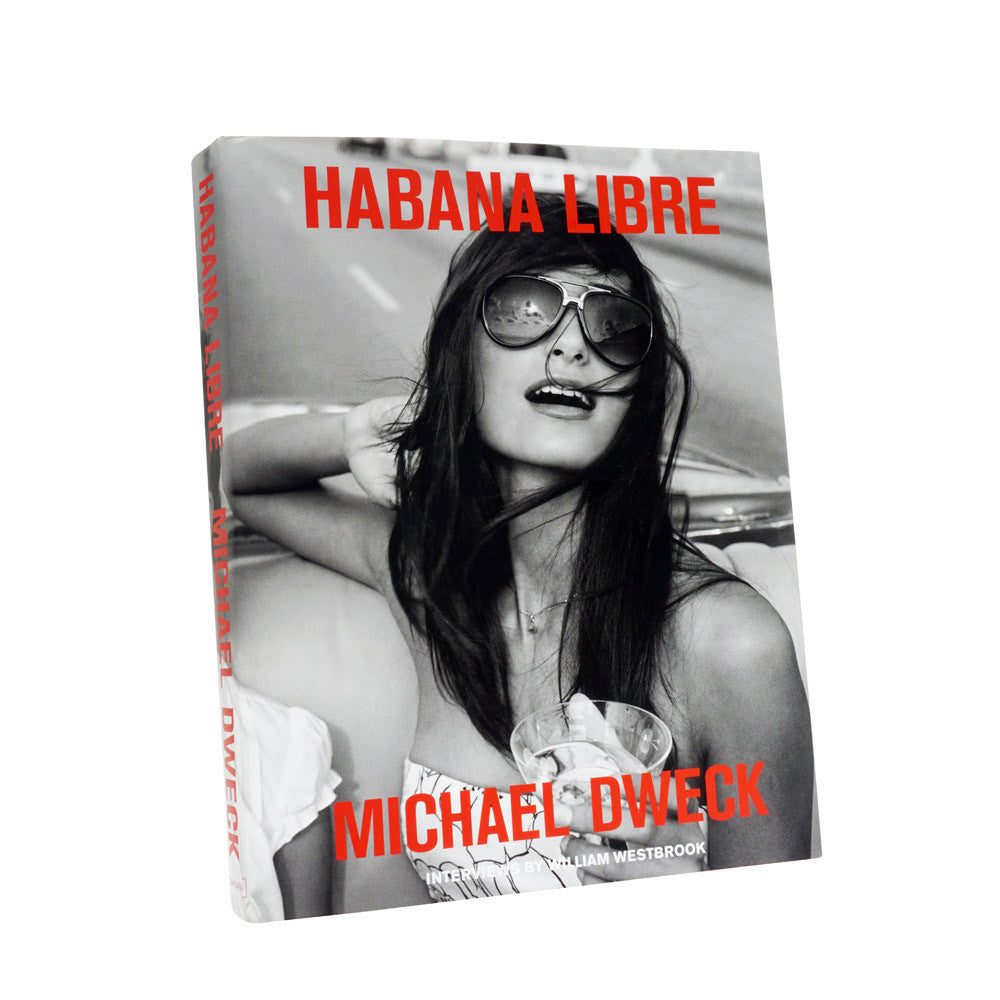

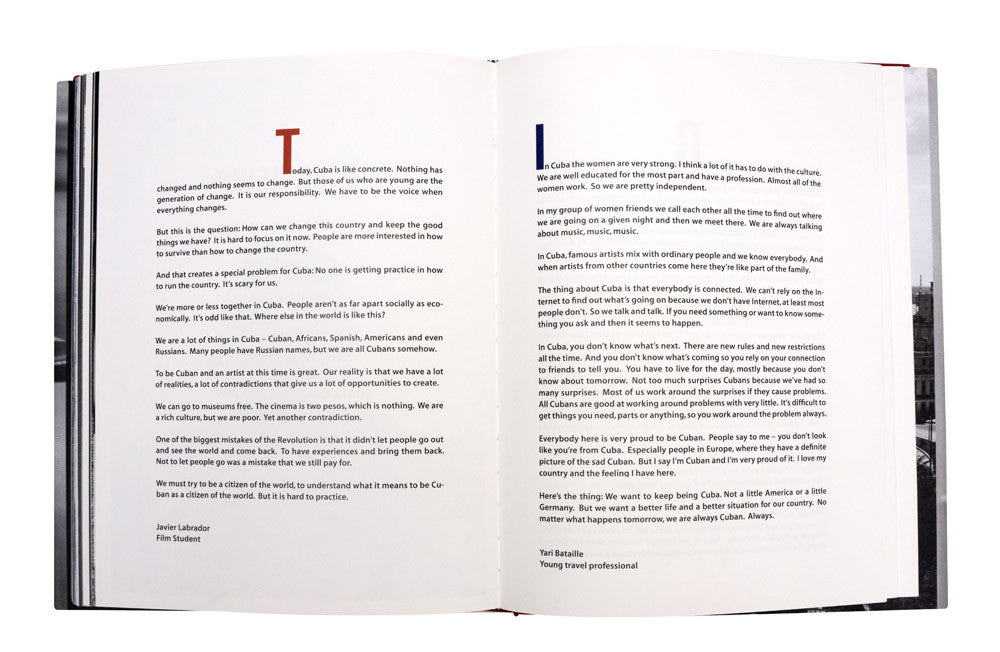

Michael Dweck: Habana Libre

Interviews by William Westbrook

Published by Damiani editore, Italy

290 pages, 214 duotone plates, 21 color plates, 9.75” x 12.5”, 3 gatefolds

Cloth bound with dust jacket

First edition of 3000 (Sold out)

Michael Dweck: Habana Libre

The limited edition printing – hailed as “a sunbaked who’s who of Cuba’s cultural elite…” by The New York Times is Dweck’s personal exploration of Havana’s hidden creative class.

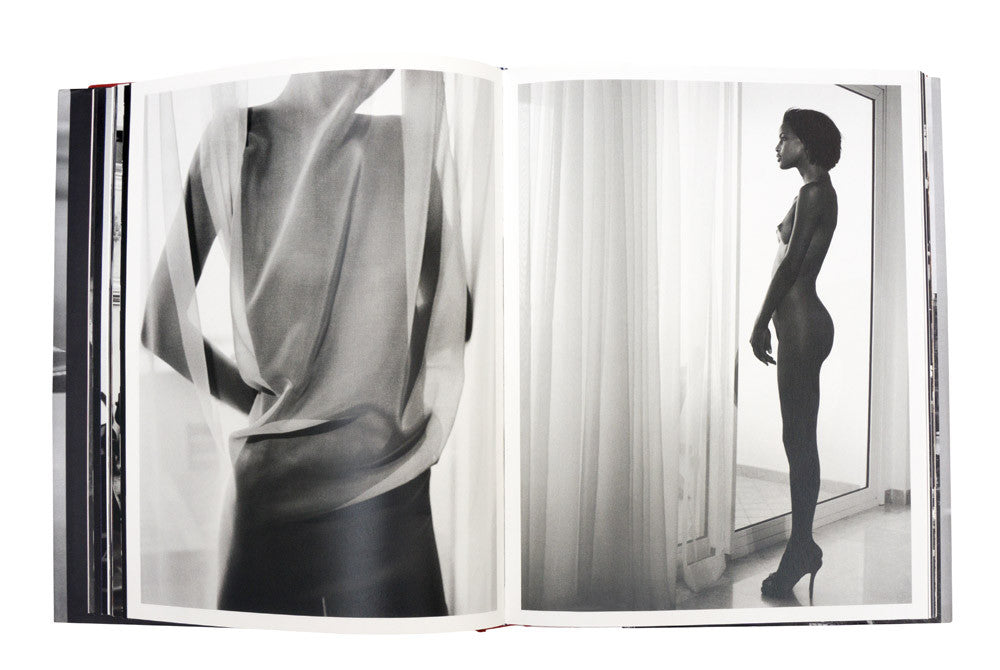

Habana Libre is a stunning contemporary exploration of the privileged class in a classless society: a secret life within Cuba. Michael Dweck’s photographs are exhilarating, sensual and provocative, with a sexy and hypnotic visual rhythm.This is a face of Cuba never before photographed, never reported in Westernmedia and never acknowledged openly within Cuba itself. It is a socially connected world of glamorous models and keenly observant artists, filmmakers, musicians and writers captured in an elaborate dance of survival and success. Here too are surprising interviews with sons of Castro and Guevara as well as many others who define the creative culture of Cuba and give it texture and substance. Habana Libre is not a media-fabricated Cuban postcard of crumbling mansions or old American cars, but a revealing and contemporary work by an artist adept at capturing the quiet gesture, the sensuous eye and the proud and provocative pose of that most romantic of contradictions: Cuba.

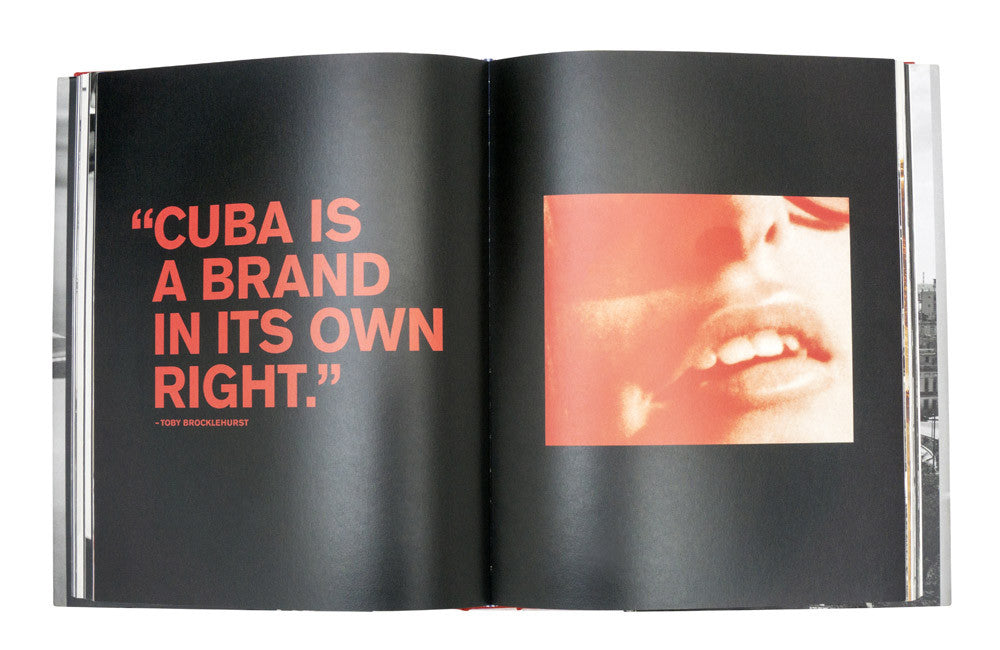

“Habana Libre is a story suggested, never told. Its subtext is an allegory of seduction, a ‘forbidden island’ that embodies a provocative mix of danger, tension, authority and mystery; teeming with an intoxicating air of sensuality and a rhythmic, almost hypnotic undercurrent.” – Michael Dweck

A portion of the proceeds from the sale of Michael Dweck: Habana Libre will go towards supporting the Cuban art community through the American Friends of the Ludwig Foundation of Cuba.

- Michael Dweck: Habana Libre

- Large format hardcover: 24.7 x 31.8 cm (9.75 x 12.5 in.) 290 pages, 214 duotone plates, 21 color plates, 9.75” x 12.5”, 3 gatefolds

- Release date: October 1, 2011

- Interviews by William Westbrook

- ISBN 978-88-6208-184-9

- Printed and bound in Italy

- Clothbound with dust jacket

- First edition of 3000 (Sold out, Art Edition available)

Also available in a limited edition (100) Art Edition Box Set with a book and a silver gelatin photograph, both signed by Michael Dweck

The duotone illustrations are made with a special treatment for black and white images that produces exquisite tonal range and density. All color illustrations are color-separated and reproduced in the finest technique available today, which provides unequalled intensity and color range.

About Michael Dweck

Michael Dweck is an American photographer, filmmaker and visual artist.

His work has been featured in solo exhibitions around the world, and become part of important international art collections. Notable solo exhibitions include Montauk: The End, 2004, a paradisiacal and erotic surf narrative set on Long Island; Mermaids, 2009, which explored the female nude refracted by river waters; and Habana Libre, 2010; an intimate exploration of privileged artists in socialist Cuba, which made him the first living American artist to have a solo exhibition in Cuba. These and other works have also been published in large, limited-edition volumes.

Previously, Dweck studied fine arts at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York and went on to become a highly regarded Creative Director, receiving more than 40 international awards, including the coveted Gold Lion at the Cannes International Festival in France. Two of his long-form television pieces are part of the permanent film collection of The Museum of Modern Art in New York. Michael Dweck currently lives in New York City and Montauk, N.Y., where he is finishing his first feature-length film.

“a sunbaked who’s who of Cuba’s cultural elite…”

– New York Times

“Dweck reveals the provocative, intoxicating images of Cuba’s creative class…”

– Vanity Fair

“Dweck captured the secret side of Castro’s Communist capital, with all of its combustible energy…”

– Vanity Fair

“a seductive look at Cuba’s creative elite ”

– Newsweek

“Dweck’s Habana Libre shatters boundaries in more ways than one…”

– Interview Magazine

“Dweck’s Habana Libre reveals a secretive collective of artists making work that treads a fine line between conceptual and subversive…”

– Nowness

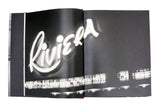

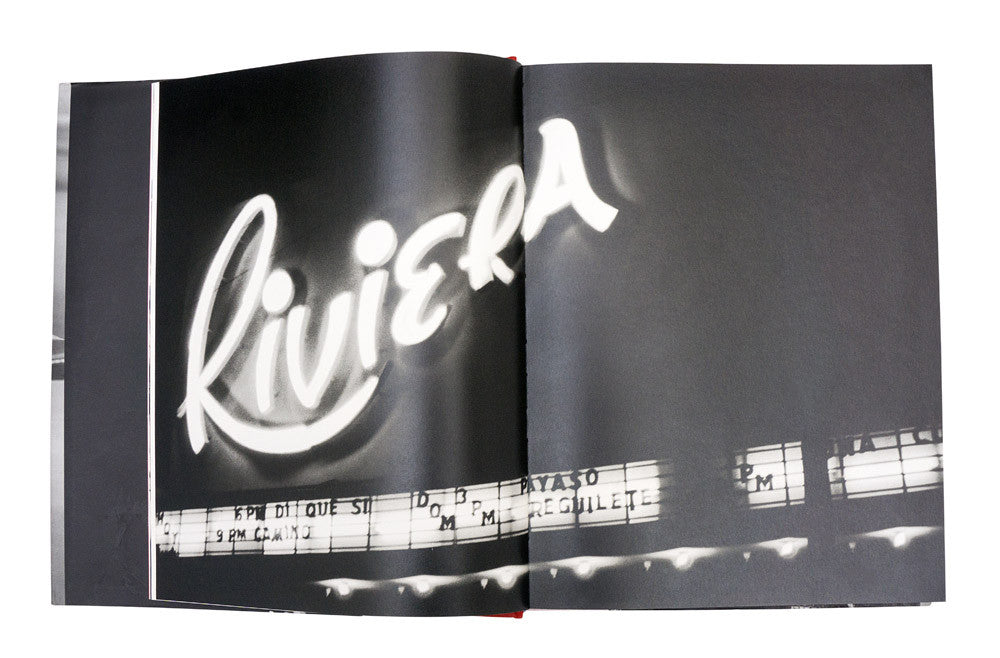

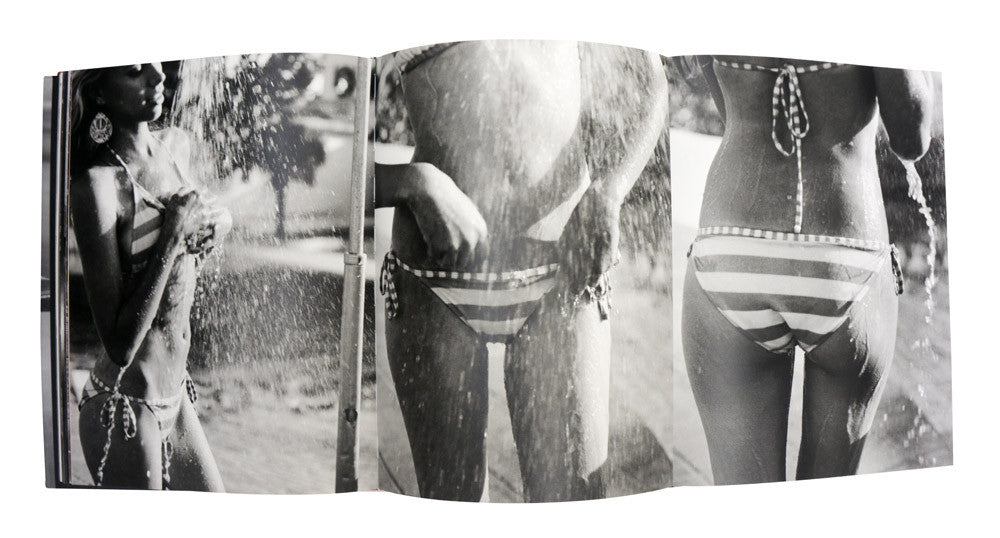

Tropicana 4. La Habana, Cuba 2010

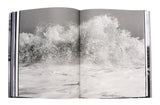

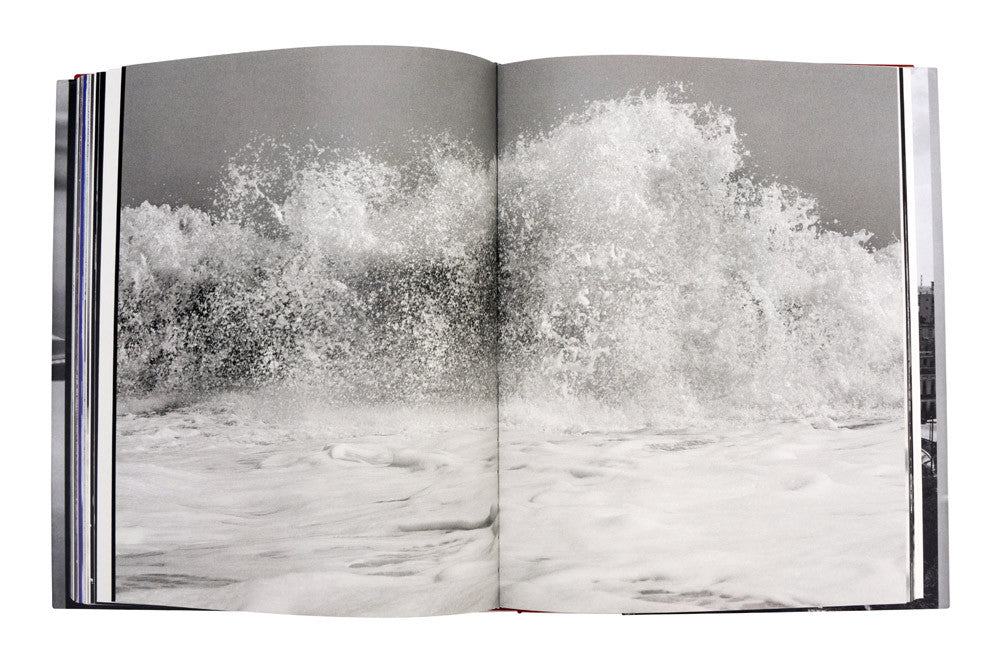

Tropicana 4. La Habana, Cuba 2010  Wave 2. La Habana, Cuba 2010

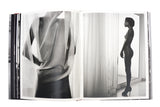

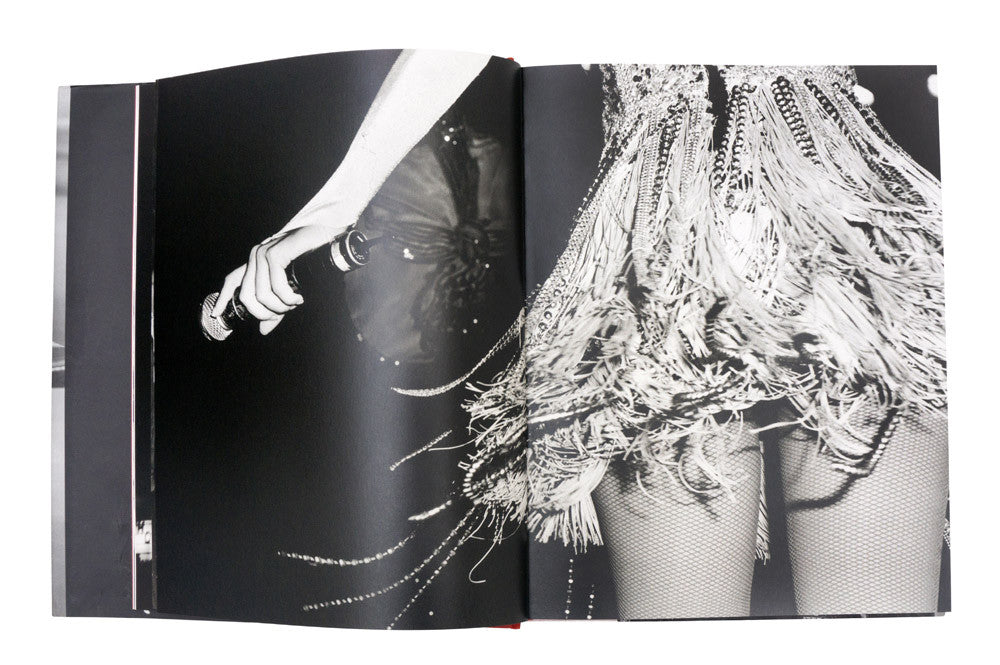

Wave 2. La Habana, Cuba 2010  Legs. La Habana, Cuba 2010

Legs. La Habana, Cuba 2010  Januaria 4. La Habana, Cuba 2009

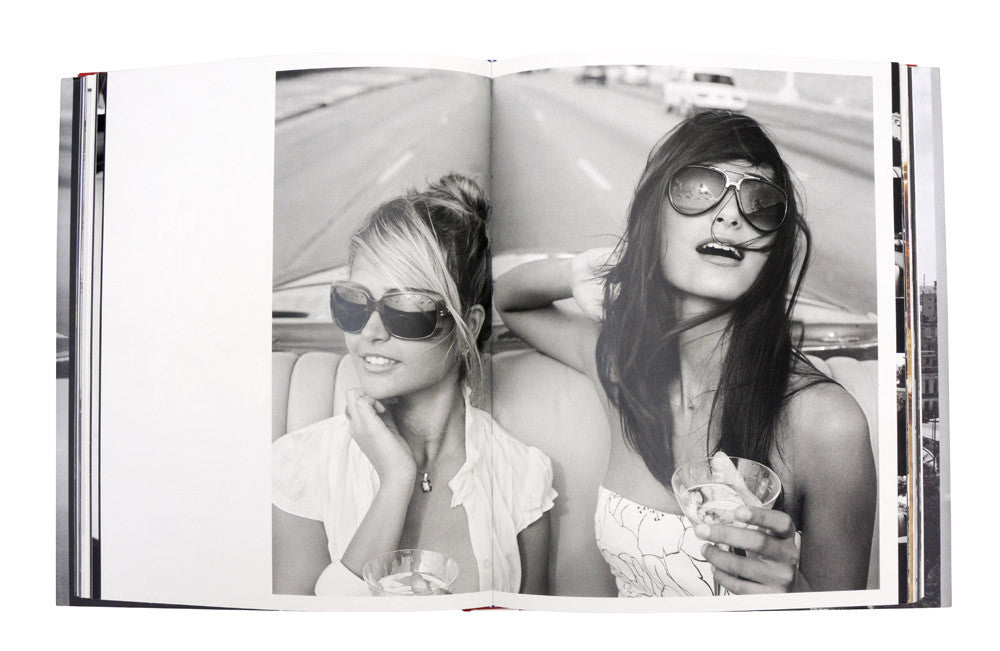

Januaria 4. La Habana, Cuba 2009  Skate kids on Avenida de Presidente. La Habana, Cuba 2010

Skate kids on Avenida de Presidente. La Habana, Cuba 2010  Ibis at the Nacional. La Habana, Cuba 2010

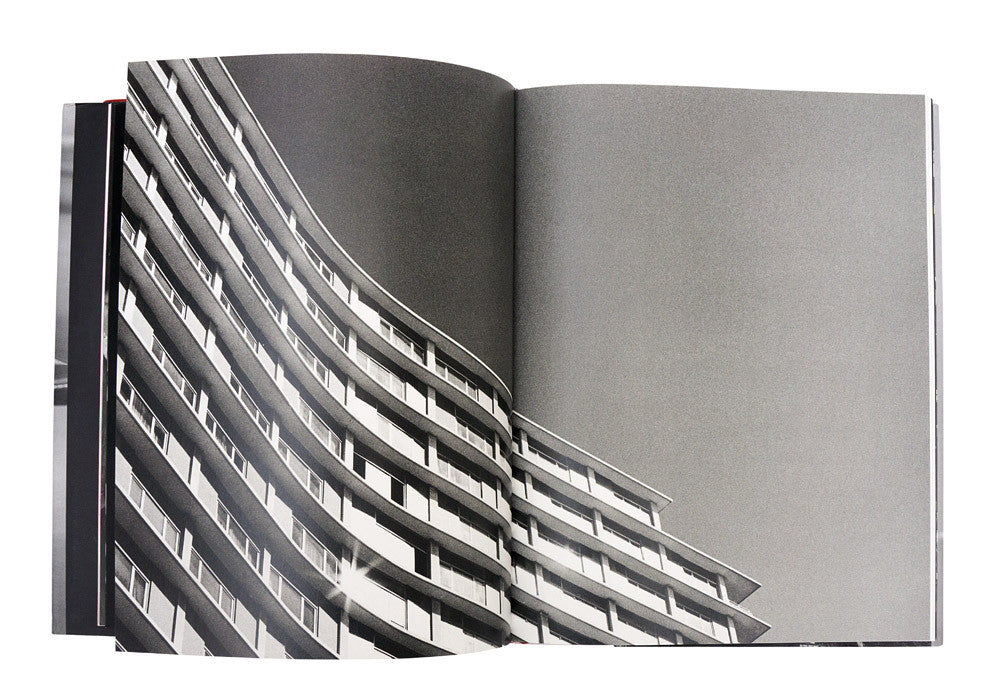

Ibis at the Nacional. La Habana, Cuba 2010  Sun. La Habana, Cuba 2009

Sun. La Habana, Cuba 2009  Tiki Bar. La Habana, Cuba 2009

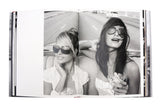

Tiki Bar. La Habana, Cuba 2009  Ludmila at Club Habana. La Habana, Cuba 2010

Ludmila at Club Habana. La Habana, Cuba 2010  Januaria 2. La Habana, Cuba 2009

Januaria 2. La Habana, Cuba 2009  Smokin’. La Habana, Cuba 2009

Smokin’. La Habana, Cuba 2009  Tropicana 8. La Habana, Cuba 2010

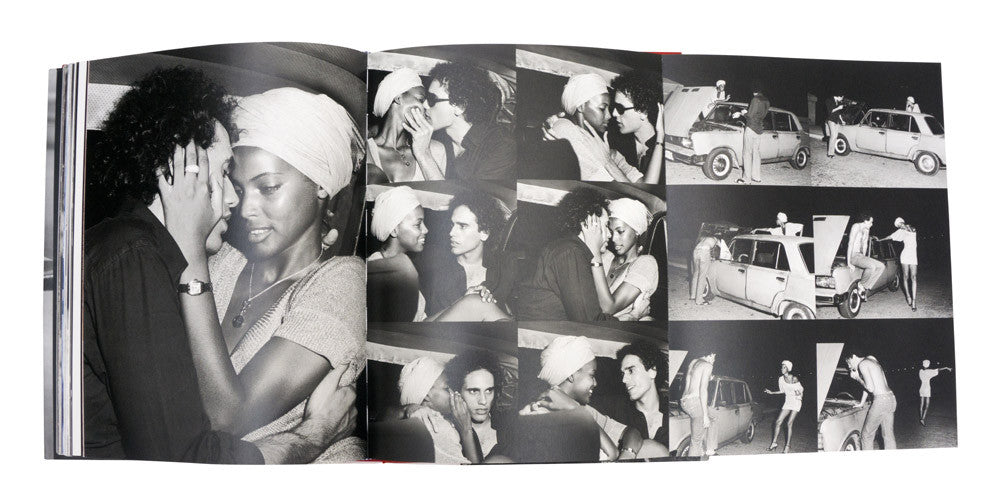

Tropicana 8. La Habana, Cuba 2010  Steamy night. La Habana, Cuba 2009

Steamy night. La Habana, Cuba 2009  Installation at Fototeca de Cuba Museum, La Habana 2012

Installation at Fototeca de Cuba Museum, La Habana 2012  Fototeca de Cuba Museum, La Habana 2012

Fototeca de Cuba Museum, La Habana 2012  Exhibition poster. Fototeca de Cuba Museum, La Habana 2012

Exhibition poster. Fototeca de Cuba Museum, La Habana 2012  Installation at Fototeca de Cuba Museum, La Habana 2012

Installation at Fototeca de Cuba Museum, La Habana 2012  Installation at Fototeca de Cuba Museum, La Habana 2012

Installation at Fototeca de Cuba Museum, La Habana 2012  Opening night at Fototeca de Cuba Museum, La Habana 2012

Opening night at Fototeca de Cuba Museum, La Habana 2012  Installation at Staley Wise Gallery New York, 2012

Installation at Staley Wise Gallery New York, 2012

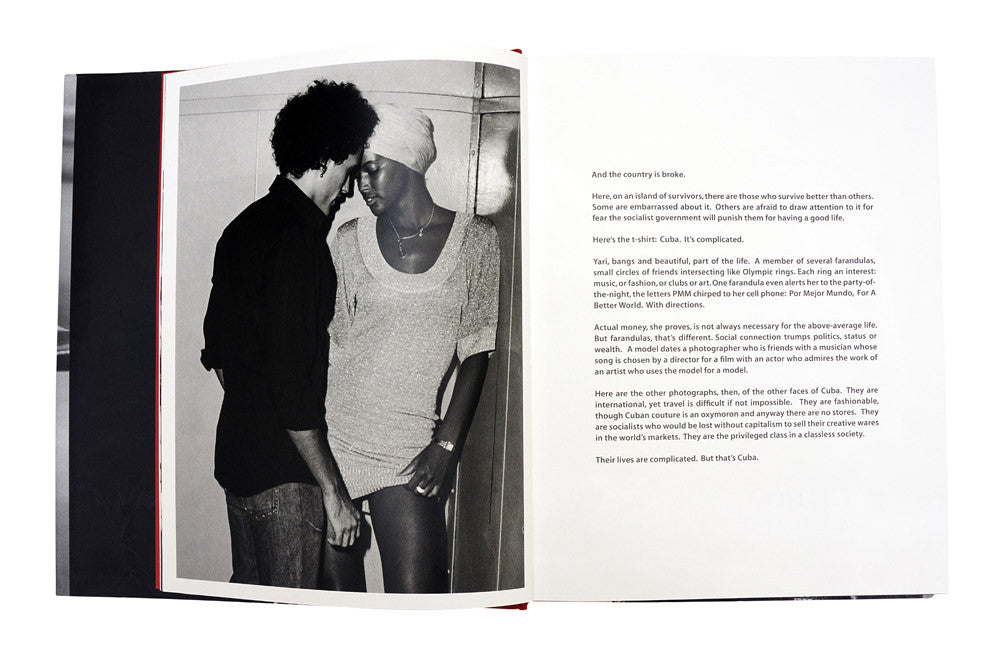

Habana Libre is something of an island intrigue, playing on the theme of privilege in a classless society, beauty and art in one of the last communist capitals. It explores the charmed life in Cuba among the creative elite as embodied in a particular farandula or clique of well connected, accomplished, and comely friends. The elegance and intimacy of this creative social world and the identities of some of the players adds to the mischief, given that this is happening in Castro’s Cuba. As interloper, I am pursuing a latent idea that develops as it goes along, subject to my own predilections and intuitions and what I find along the way. Allowed access to such a world inevitably affects one's perception of it, as in the difference of glimpsing something from without and the view from within. Just as in my other projects, I am exploring an allegory of an all too worldly paradise beset by threats from without and by new hierarchies from within, and the inescapable claims of the flesh. Just as the Chinese have made their curious pact between capitalism and communist ideology, Cuba must resolve the contradictions of its revolutionary rectitude and the powerful allure of tropical pleasures. In that tension, as in any autocratic society, there is also the poignant pleasure of a hint of danger, of power at play, and the threat of unforeseen consequences of breaking unwritten, unspoken rules. Habana Libre expresses my experience of Cuba emotionally, in the way it made me feel to be there and to be caught up in this exclusive world, but in this narrow, delectable slice of the Cuban experience, I can't help but see some forming outlines of Cuba's future.

Whitewall Magazine interview with Michael Dweck

Whitewall Magazine interview with Michael Dweck

Whitewall: How did you first get involved in this exclusive creative class of Cuba?

MD: I guess the impetus came from my initial attractions to Cuba, both the romantic and realistic: the danger, charm, sensuality. There had to be a way to capture it all – particularly the seductive elements – and use participation and observation in parity to pull out a more authentic picture of life – and art – on the island. So even though I didn’t know exactly where I’d be pointing the camera, I knew access would be key – especially there in Castro’s Cuba. Luckily, as my friends always say, I’m very lucky at getting lucky.

My second day in Havana, I was invited to a party by a wonderful Brit I’d met the previous night at another artist’s house. It’s one a.m. A modern-style 1950’s oceanfront; waves are crashing over the seawall; a roaring crowd of 200 people is dancing between the ocean spray and a turquoise pool in 90-degree heat to the music of Kelvis Ochoa and his band. These aren’t fat woman smoking cigars for tourists. These people glow, savor everything and never stop dancing. They’re beautiful in all definitions of the word and this is them in their element.

So this was where the idea really embedded and began to mature – in the steamy midst of this merrymaking and around this group of 20-or-so; what the Cubans call a farandula, an elite clique of well-connected, accomplished and comely friends. This is what it meant in the foreword to the book when it says, “a model dates a photographer who is friends with a musician whose song is chosen by a director for a film with an actor who admires the work of an artist who uses the model for a model.” That’s how they work. I was lucky enough to fall into – and be embraced by – a phenomenon unique to Cuba. The mischief, the elegance, the privilege – and even the irony. It made the perfect subject.

Whitewall: What was their initial reaction to an American taking these pictures and covering this lifestyle that previously has been in the dark?

MD: As expected, the artists were wondering where the hell I came from. How did this American get invited into their “secret world?” (They seemed reluctant to speak to me, firstly because I was American – which comes with its fair share of baggage – and secondly because this was so obviously a privileged class of people living in a classless society.

But once we started familiarizing ourselves with one another and working together, the circle warmed up and started speaking to me like I was another artist in the fold. I think it helped that I made it clear from the outset that I had no intention of using my photography as third-party reportage or some “third world” voyeuristic documentary. National Geographic can do that. I was there to borrow the scene’s vibrancy and point up semblances of what I saw as a small, remarkable group in the belly of a large, misrepresented society.

Habana Libre explores the allegory of worldly paradise in surroundings anything but paradisiacal – the threats besetting it from outside parties and inside hierarchies, its relationship to the less fortunate… But it also pokes an eye into everyday Cuban life and asks subject and audience (Cuban and American, respectively) to question whether the thing we’ve been told about one another is true.

Whitewall: When you cover these sorts of social groups do you begin to establish relationships with those in them? Do you ever maintain contact with these people after your project has ended?

MD: That’s a good question. I’m hyper-curious about people in general. I think a photograph has to reflect that about its photographer to feel sincere or expressive. A good photo doesn’t just answer the question “what do you look like?” or “what are you wearing?” but also, “who are you?” “What are your passions?” “How do you survive, succeed?” That interest in those second answers helps me disarm people in a way and, I think, allows me to go further in terms of concept and execution.

This was a huge advantage in Cuba where, like I said, I was initially greeted with some doubt and skepticism, not only by the government, but the people. Then you have my work, which leans thematically toward the seductive and revealing, which requires more trust, more amity to thrive. When I see certain sparks or suggestions in a subject, little wild child-like glints, and I can lock that down in a photograph it creates indescribable bonds. Not only did I bond with these people as a fellow artist, but I won a lifetime of familiarity from taking their picture. So, yeah, there will always be subjects who I remain in contact with. Rachel Valdez – the painter featured on the cover of Habana Libre – is a good example. She and I still write or speak at least twice a week and plan to collaborate on an upcoming project in Paris.

Whitewall: What was your experience like in photographing the sons of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara? Did you feel any sort of pressure given that this was the first time they had been photographed in this way?

MD: I find portraits work best if I don’t have a specific intention of what I’m hoping to achieve. Seeing as how both Camilo [Guevera] and Alex [Castro] are photographers, we had that base of understanding and got along quite well. Camilo and I actually lived in the same building in Havana. We shared samples with each other and spent a lot of time talking about the life of an artist in Cuba – and the US. Every time I got together with either of them, it was like a freewheeling photographic jam session – and these are men who’ve never before been photographed or interviewed by anyone.

Remember, these are literally the sons of revolution and now, as artists, they’re putting their own spin on the word; what it means to rebel. I know Alex has been reinterpreting the work of 19th century Spanish master painters and Camilo has a series of portraits that explore subjects banned and/or taboo in Cuba. One of his photos – a pair of female lovers – was considered illegal in Cuba until recently.

You have to remember that Fidel is a patron and sponsor of the arts, but artists will be artists. So the Cuban creative maintains a duplicitous position in his or her representation of the island. There’s a very curious push-and-pull to observe between endorsing talent and controlling its message.

Whitewall: These sort of creative groups exist in other countries as well, what was unique about these particular artists given that they have grown up in such a fundamentally different society?

MD: Well, for starters, you have a group of artists I just mentioned who aren’t really allowed to create anything that could be interpreted as critical, overtly or otherwise, of their government. And, simultaneously, they maintain certain places of privilege in a so-called underprivileged country. So what this breeds is a very tight-knit, even insular, group that’s extra-societal in one sense and the very epitome of that same society in another.

They collaborate and celebrate like they’re players in a Parisian salon in the 1930’s, but are also wired as artists to subtly provoke and defy like the same salon that was in Franco’s Barcelona. Cubans in general juggle that duality – defiant and humble, tightly-controlled and indefinitely resilient. Their artists are no different. They just have more money. They have parties. They can travel freely. But wouldn’t you know it – they always come back home.

I asked one painter why she returned to Cuba after a recent visit to Europe.

Her answer; “If all artists left Cuba, there would be no Cuba.”

Whitewall: What is different about this project compared to some of your other series such as The End: Montauk, N.Y.?

MD: All of the implied subtext – seduction, isolation, the individual’s interpretation of freedom – was intended to be common. I call “Habana Libre” the final installation in my trilogy about island life. (“Montauk…” and “Mermaids” being the predecessors.) And when I frame this in terms of a trilogy, it is, like it sounds, informed by film.

I thought quite a bit about cinema when making the books – Havana in particular. I mulled over David Lynch’s aesthetics in “Blue Velvet” or “Wild at Heart,” the contemporary neo-noir sensations of “Body Heat” or Billy Wilder's “Double Indemnity.”

If you allow yourself to conceptualize the breakdown of a photograph as an individual frame of some missing motion picture – one millisecond captured from a larger narrative – you can start to move beyond what might be seen as a static and limiting impression of the medium which might make a black-and-white photo seem dormant or dead. Yes, these photos are frozen in that they’re of the past and remove a colorful dimension from real space, but therein lies the seduction and the life.

I don’t know if there really are any other books that present themselves like this – maybe the fantastical “Cowboy Kate” from the 60's. I conceptualized “Montauk” with a mix of nostalgic fantasy and a real bygone youthfulness, and “Mermaids” wore its impressionistic abstractions on its sleeve, but “Habana Libre” is unique in that its entire expression and narrative is terrestrial.

We’re dealing with people living buoyant, cinematic lives and I want the audience to share in that, feed on it. A single photo won’t borrow all the corners of that cube and give it away in two dimensions. But I think a book like this that doesn’t treat itself like “just a photobook” and whose images and narratives refuse to treat their subjects like “subjects” can go further in making its points, whatever island they may reference.

It’s also interesting to note how much has changed even since these photos were taken in 2009. Last month, the Cuban government issued more than 85,000 licenses for private businesses. Obama recently relaxed the rules about Cuban-Americans sending money home to family members. Cubans can now sell their homes. The island is changing and I’m glad I was able to put this together when I did, right on the eve of what may prove to usher in a sea-change.

Whitewall: How is the process for putting a book like this together different than an exhibition? When do you know you have enough photographs and can stop the process?

MD: I am not very good at stopping the process. I let it stop me in a sense. If you ask anyone that I’ve photographed they’ll tell you that when I say “this is the last roll,” we inevitably keep going until the film runs out. It’s the only way I know how to work – let your excitement go until you run out material – or you subject calls it quits.

I went to Cuba eight times and shot more than 500 rolls of film over a period of 14 months. William Westbrook, who wrote the book's passages, came along for almost every trip and conducted hours and hours of interviews. So we came home with an overwhelming amount of material and, to make it more taxing, was intent on making it stream into a narrative.

Whitewall: Do you have a method for narrating through images for a project like this?

MD: Narratives are the most difficult photographic books to do because they need to work on many levels. Each photograph needs to be strong on its own. Spreads with side-by-side shots need to exhibit a certain symbiosis. Then all the images need to develop together into something complete and linear, again, like a film.

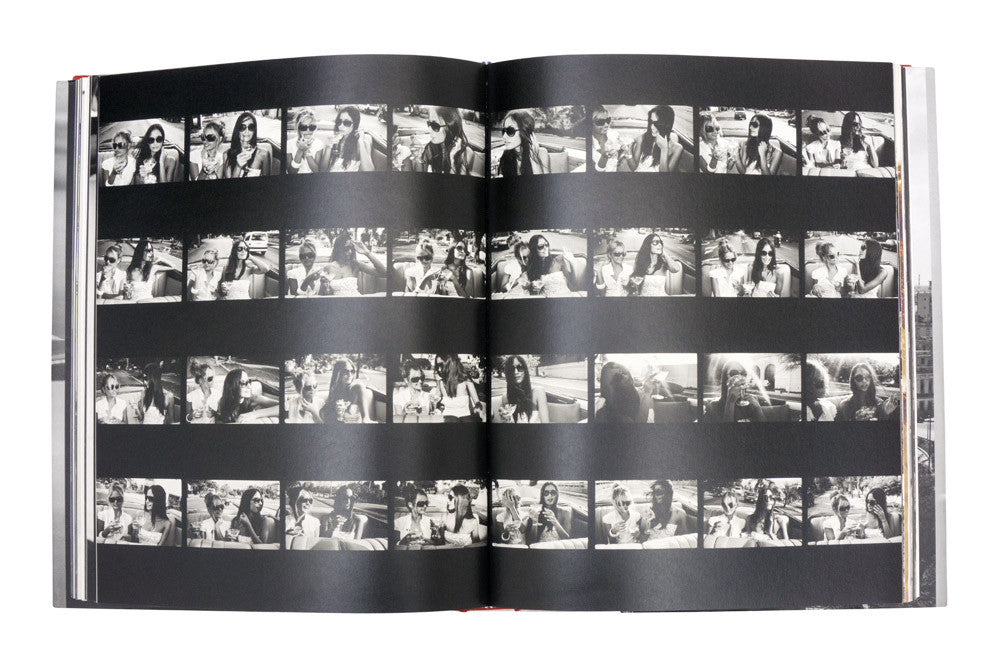

The editing, all said, took more than three months: My editor Jupiter Jones and I went though all of the contact sheets and pulled the strongest images – not just the best shots, but the most relevant. We had about 500 at that point and started to organize them by scene and spread them out onto tables throughout the studio like a three-dimensional storyboard. You walk through and think about flow, about pacing, about visual rhythm, about arc. We needed to connect the dots, so to speak, and make sure the sequence fit the story we wanted to tell.

Editing something like this for an exhibition was more difficult. I wanted the book to stand alone as a work of art and not be a thinly-veiled catalog for the exhibition. Each selection had to be carefully chosen for the hanging to maintain its thematic thread.

For the San Francisco exhibition at Modernism, owner Martin Muller and I each spent two weeks making separate selects and then swapped lists. We then spent a couple more days with each other’s selects and made the final order. It was a lengthy process.

Whitewall: What challenges did you come across when photographing this series?

MD: I mentioned the challenge of access, getting into these tight circles and gaining trust. But even getting into the position to do so, getting into the country, had its own roll of logistical and practical hang-ups.

Preparation for each trip took at the very least a month to plan. I’m not fluent in Spanish and my writer Westbrook doesn't speak any, so I had to work things out with my on-ground translator (who unfortunately didn’t speak great English. Lucky, my wife Cecilia is Argentine and helped out with a lot of the transcription when I got home.) I had to get financial situation in order since Americans don’t have access to ATM’s or credit cards. Shooting both daytime events and nightlife kept me literally working around the clock. A day that started at 6 a.m. and ended at 3 a.m. wasn’t unusual.

Then there are the bureaucratic dances – getting approvals down the line and the endless meetings with government official and cultural ministers, arranging for letters of support from Cuban artists and museum curators. It’s not like flying into Mexico and going through customs. We were functionally knocking on Cuba’s door wearing the colors of the enemy and carrying 100 pounds of photography equipment.

All said, the government was surprisingly welcoming and accommodating. I’ve even been invited back for an exhibition at Fototeca in February. If that proposal passes a governmental review, it will be one of the first solo exhibitions for a contemporary American artist at that museum since the revolution.

Whitewall: Were you faced with people who didn't want this side of Cuba revealed?

MD: This is a peak at a face of Cuba never before photographed, never reported in Western media, never acknowledged openly within Cuba itself. Still, everyone we met – including the sons of Fidel and Che – were welcoming and spoke openly.

It will be interesting to see if the book itself receives the same reception in Cuba that I did. I know there have been grumbling from Cuban-American ex-patriots who feel the images misrepresent the larger society, though it seems they’re missing the narrative’s intention and focus.

Of course I also expect there to be those on the island who balk at some of implied irony in the juxtaposition between the life of these artists and that of the farmers and even neurosurgeons who live on the equivalent of approximately $16 a month.

My replies to those criticisms are in the book. This is a self-justifying medium. You can’t argue with a photograph.

Whitewall: Which images from this book mean the most to you?

MD: They’re are all meaningful in their own way, not so much for what they might represent in the context of the full work – whether that’s the social commentary or allegorical angle – but for the subjects themselves. These are photographs of artists living easy in a place where it’s not easy to be an artist – or to live easy in general. Each shot, for me, revisits some of that complexity.

There’s also the presence of a reawakening, personally, when I review the photos. I reencounter the sensuality of the island; I hear the music of Chucho Valdez, Celia Cruz, Ibrahim Ferrer. For all its shortcomings, the country Kennedy once called an “unhappy island,” overruns with visceral joy and beauty.

Whitewall: Are there any photos that have an interesting anecdote that you could share?

MD: I was thinking the other day that if I had the opportunity to do the book again I think I’d include anecdotes for a portion of the photographs. Just to share some of the backgrounds that enforce – or belie – certain shots.

The cover photo of Rachel and Gisele for one. Rachel, the painter I mentioned earlier; she just understands how to project herself in a photograph and the effects are mesmerizing. She doesn’t exude optimism and sensuality so much as she shares it. It defines a lot of what I felt about Cuba.

In another picture, one of a couple in the elevator, there’s a fundamental of island life that deserves caption. There are elevators in all these buildings where families have lived for generations and they’re always breaking down. So, if you want intimacy, you meet your lover in an alleyway or in an elevator—preferably in one that’s broken.

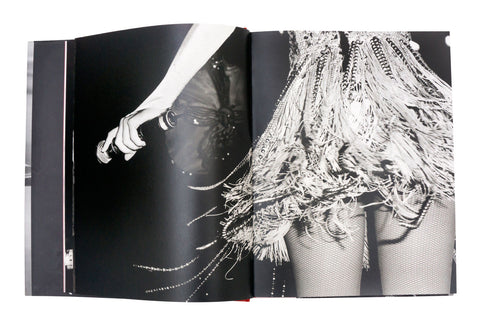

The photographs I made at the Tropicana come to mind too. The performers appear obsessed with games of sex, but they’re really obsessed with the game itself. It’s a pastime of signs and flirtatious signals both overt and subtle. It’s like burlesque, it take seduction to the limit without taking it overboard. I see the suggestiveness of it as a challenge. If I can freeze that moment and still make the audience feel that suggestion, I know I’m doing something right.

Whitewall: What are you working on currently?

MD: The “island life” trilogy, even the themes, locked so much of my attention that it’s almost a vacation to move on to some of the other things I’ve conceptualized, but couldn’t pursue. I’m starting work on a project in Europe that will be pretty large in scope and scale. Think multimedia, where “media” can mean painting and sculpture as well as photography, film and audio.

I don’t want to give too much away, but it should be fun.

Huffington Post Welcome to Cuba, Asshole by Michael Dweck

Huffington Post Welcome to Cuba, Asshole by Michael Dweck

In preparing for my first trip to photograph in Cuba, I prepared myself for a country for which my country had already prepared me.

The "unhappy island" Kennedy cursed. A place Bush, the younger, warned was devoid of pleasure, "a tropical gulag," a slum where it was "against the law for three Cubans to meet without permission," (something I imagined him researching when drafting the Patriot Act).

I scrambled before my flight to get my hands on the best anti-depressants, anti-perspirants, anti-freedom necessities (film, lenses, the name of a good lawyer). I told my family and friends where they could reach me -- not that they'd be able to. Reagan told of a Cuba that lacked basic material possessions, much less freedom. Horse carts were apparently the norm, so phones and mail, it could be assumed, were out of the question.

I arrived to a March heat I can't describe without breaking a sweat. This was the mattress-thick humidity of which I'd been warned. It hung over coastline palms and Havana's worn charms with a stubborn omnipresence. Bush's voice rang its caveats in my ear: "this is the first invisible gunman guarding the prison that is Cuba" and I felt a palpable sense of dread in my stomach lined with the scarcest trace of hope.

That was 6 p.m.

by 11 p.m. the next night, I was soaked in sweat and picking my jaw up from the ground like a cartoon duck recovering from an anvil-whacking. Just twenty-seven hours into my stay in poor, sad, hellhole Havana, I walked into a seaside party that could refute six decades of American rhetoric; a tropical shindig that could wow Caesar, Cleopatra, Bond, Warhol, the Rat Pack, the cast of Jersey Shore... you get the point.

Waves crashed over the seawall on a 1950s-style oceanfront as 200 beautiful Cubans danced poolside in a 90-degree mist to the music of Kelvis Ochoa and his band. This wasn't an assembly of fat, disgruntled women rolling cigars and cursing Gringos while their grandchildren begged in rags. This was paradise -- for a tourist, for an American photographer, for anyone. And the best part? It happened every night.

My own voice rang in my ear:

"Welcome to Cuba, asshole."

What I was lucky enough to have stumbled into (with the help of a friend I made at my hotel) was a farandula -- a clique of well-connected, influential Cubans. In this case, they were artists (painters, photographers, actors, film directors, dancers, musicians, models, etc.) and they represented a side of Cuba that our well-informed presidents either missed, dismissed or intentionally ignored. These folks were glamorous, obstensibly well-off and, above all else, free. Watching them dance and mingle around the pool, I stopped worrying about my impressions and started worrying about theirs -- their dark-eyed glances both sexy and suspicious. Did they see a wild-haired photographer cut from their cloth or some dumbass capitalist American with a pricey camera around his neck? Thankfully, after a few introductions, a few drinks and some enjoyable mingling, the group seemed to accept me as another artist in the fold. And like that, I became their pale tagalong; an honorary part of a farandula.

On a typical night on that trip (and on my seven return trips) I'd catch up on the group's whereabouts via text message (yes, they have phones, mostly smartphones, though reception is spotty and Words With Friends has yet to catch on) and we'd meet at an artist's or musician's studio somewhere in Havana. Things would start out like they must have in the Parisian salons of the 1930s and then, as we drank more, chatted and migrated about the city, they'd evolve into scenes from Studio 54 of the 1970s.

The artists (people like Rene Francisco, Rachel Valdez, Roberto Fabelo, et al.) danced, painted, drank, screened films on giant stucco walls in their courtyards, collaborated with one another, wrote and chatted while I photographed (and eventually joined them in the dancing, painting, drinking, etc.).

Now -- if it's not yet clear -- my intention was never to use my photographs to prove a social or political point -- no more than it was to use them as an excuse to drink 18-year-old scotch with glowing actresses and smoke Cuban cigars with famed directors like Jorge "Pichi" Perugorria (though I didn't shy away when the latter offers presented themselves). My goal, as I've said before, was to peek into everyday life on the island and pose the question to subject and audience (Cuban and American, respectively) whether the things we've been told about one another are true.

And the answer, it seems, was "yes" and "no."

Yes, Cuba is as poor as America is rich -- maybe poorer -- though neither country is without the notable exceptions they keep under wraps. Cuba's poverty is economic, not social. So, no, Cuba isn't unhappy, isn't a tropical prison, isn't a torrid police state. Cubans carry the burden of their government's restrictions -- and our government's embargo -- but they do so with a sincere hope and visceral joy that even America's well-off seem to lack.

In a way that won't make sense to many Americans, the well-off Cuban artists I met and photographed seemed the embodiment of the hopes of their poorest neighbors. (I know what you're thinking, that'd be like calling the Kardashians "signs on the road to America's recovery.") But this is different.

The existence of this farandula, for me, doesn't paw at the disparity between the haves and the have-nots, but rather provides a vision of what the island can be. Its members serve, in ways, as ambassadors for a country that needs ambassadors more than anything. They travel freely, spend lavishly and live lives of relative luxury. (The operative word being "relative." by U.S. standards, the artists -- which include the sons of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara -- would still be considered middle-class). And as for the rest of Havana -- well, take a stroll on the Malceon after dark on any weekend and tell me if the denizens seem to be quaking in cloistered groups; if the teens are faking their smiles and the lovers' their passion. Then go ahead and scan my photos of the all-but-unannounced Peace Without Borders concert in Revolution Square featuring Juanes and Miguel Bose.

Fewer than three people? Try more than a million.

All porcelain hope and horsecart mobility? Don't fucking bet on it.

I think it's important to note again that Habana Libre wasn't assembled as propaganda or counter-propaganda or anything in between. It doesn't represent its photographer's point, so much as his point-of-view; my vision of Cuba and no one else's. It represents an island -- or my idea of one -- ripe with seduction, mystery, sensuality and, yes, a little danger. The Cuba depicted in my book isn't an overtly political place, but a thoroughly human one both accepting and defiant as it teeters on the cusp of change. At least that's what I thought when I took the photographs. When I flip through the pages of the book now, or prepare photographs to hang at the Fototeca de Cuba Museum in Havana, there are moments when I'm surprised to find definite points -- political or otherwise -- rising up from my overarching narrative. The images are mine, the impressions mine, but the meaning belongs to the subjects and their country and no one else. And with this dichotomy in mind, it's only fitting that these definitions and serendipitous points rise from a place that most Americans -- most Cubans, for that matter -- will never get a chance to see: a talented heart beneath the ribs of a misrepresented society.

A diamond in the rough making the best of its burial.

A pearl polished by political sands.

And, I'm coming to see, that at a certain point the analogies do more harm than good.

Cuba is just Cuba.

And leaving, for me, felt a lot like arriving -- that is, it had me doubting my destination once again.

Despite what our leaders would like us to think, there are parts of Cuba and clusters of its people that bursts with joy, with creativity, with hope -- it all just happens to be filtered through a lens through which some Americans (and some of their leaders) would prefer not to peer.

Are we being lied to? Not exactly...

We're just not being told the truth.

Paris Match interview with Michael Dweck

Paris Match interview with Michael Dweck by Michel Peyrard

Paris Match: Who introduced you to this underground intelligentsia? How did that happen? Did they trust you right away?

Michael Dweck: Looking back, I think my first trip to Havana was like walking into a nightclub – and actually connecting with that group was like picking up a woman at the bar. You see a confident, sexy woman across the dance floor. You catch her eye. You look one another over. You flirt. And, in my case, you stay together for a while and have some fun.

Only here there was something of a matchmaker – an artist friend I’d met who was part of this extended scene. He took me to this party – and it was just like seeing that woman across the room. Only now, the room is an oceanfront villa and waves are crashing over the seawall. Kelvis Ochoa and his band are playing around the pool for this wild crowd. And now the beautiful woman is a clique of 200 beautiful people.

Same rules though – I mingle, we flirt, we get to know one another. Remember these are all artists – filmmakers, painters, dancers, photographers. We spoke a common language.

I’m sure if I stumbled into this tightly-knit group of artists – this farandula – wearing a suit and talking about investment banking, they would have brushed me off. But as an artist, the attraction was mutual. We knew one another and developed a trust that allowed for an amazing amount if access.

PM: How did the various groups form? What do they have in common?

MD: I’m not sure how any group forms – not just in Cuba, but anywhere.

I suppose you start with geographical convenience and mutual interests. A lot of the notable artists in Havana went to university together or trained in the same places. They’re all creative-types so, again, they have this common language and it blooms and balloons from there. No different than the painters in the Barbizon school or the writers in Beats movement. Talented people – and in this case, beautiful people – have a tendency to flock together.

The foreword of the book touches on this – the group’s almost incestuous interconnectedness: “a model dates a photographer who is friends with a musician whose song is chosen by a director for a film with an actor who admires the work of an artist who uses the model for a model.”

That’s how things work.

PM: How could you explain us their motto (« Por un mundo mejor »)?

MD: Por un mundo mejor means “for a better world.” The group usually abbreviates it “PMM” and that’s the text message you’ll get in the afternoon if there’s a gathering that night. If you see PMM on your phone you know you’re in and you know, in less than 12 hours, you’ll be drinking a 15-year rum and surrounded by top-notch musicians and an endless supply of beautiful women who seem to salsa with an extra gear in their hips. That’s the best part of the day, hands down – getting that text is almost arousing.

Depending on your reading, the motto’s definition can list in a few directions. There’s a certain optimism and ambition when you point it outwardly: these are artists using their respective crafts to improve the world – or, at least, their world, Cuba’s world.

The more narcissistic tilt, though, is that this farandula considers itself its “the better world,” as in, “This party is only for the better world.” You can spin it both ways.

I’ve been asked if it can also be read as a motto of rebellion – which, no, I don’t really see. This isn’t Che’s “Hasta la victoria siempre.” These are artists whose definition of a “better world” is in terms of social happenings, not necessarily political ones. They’re not concerned with upheaval, so much as sex, music, art, alcohol, etc… The important things.

PM: Did they take any political positions? Do they want political changes? Are politics one of the topics of those parties? Do they talk about Castro?

MD: Most people in Cuba want things to improve: They want the embargo lifted. They want to travel restrictions ended or eased. They want more access to money.

The artists are no different but, that said, politics were never really discussed at any of the happenings I attended. These weren’t Occupy Havana rallies, they were the parties of a well-connected clique. Artists relaxed, talked about their work, drank, gossiped, collaborated on paintings, played dominoes, flirted. Why complain about foreign relations when you can salsa? Why debate the role of government when you can make love?

That said, artists will be artists – minor political points will be made in their works, albeit subtly; certain pieces will be crafted to be interpreted in different manners. But there’s a code, silent or spoken, and most of these artists know where the lines are and aim to stay well behind them for obvious reasons.

As far as Castro goes, no one I met talked about him and I attributed that to different things on different days. On one hand, there might be repercussions for anything approximating sedition. On the other hand, Castro’s government is like the weather. It’s omnipresent. It’s a fact of life. It’s there and no amount of yammering is going to break the clouds.

PM: What do they like? In fashion? Music? Do they have fetishes/mascots?

MD: Like most Latin cultures, Cubans are very sexually charged – and very open about their sensuality. Maybe it’s this confidence that makes them more beautiful – or the general seduction that hangs wet in the air like fog on shaft of a jetty. I remember passing by a hospital in Havana and seeing these nurses in their 50’s and 60’s who were just stunning in fishnet stockings and high heels. I wanted to break my leg just to have an excuse to talk to them. It reminded me of Joseph Cotten’s line in “Citizen Kane” about the myth of the attractive nurse being false – well, you can tell Orson Welles had never been to Havana.

You can’t get “Vogue Paris” in Cuba – or any magazine for that matter – but you wouldn’t glean that from looking around. The people glow with what seems to be an effortless style sense. Maybe it’s the effect of La Maison, where there are two fashion shows nightly. A lot of the women make their own clothes, but you’d never know it – you get the feeling they could walk naked in the jungle and come out dazzling in glamorous leaf-and-vine ensembles. They’re amazing.

The music is in it’s own league too – an extension of the island’s passion and pride. Seeing Kelvis Ochoa, Descemer Bueno, the sexy Sexto Sentido, the beautiful Diana Fuentes; Cubaton bands like Gente De Zona; jazz acts like Pablo Milanes’ daughter Haydee, Roberto Fonseca – that, to me, is what the Buena Vista Social Club must have been like in its prime.

Our largest concerts in the States draw 70,000 people – and those are the huge ones. The Peace without Borders concert in Revolution Square drew 1.5 million people. Imagine a million and a half beautiful people dancing, smiling, singing? That tells you all you need to know about music in Cuba.

PM: Where do these Beautiful People wander? Where and what are the hypest places (bars, clubs, restaurants)?

MD: One of my favorite aspects of the farandula is that these folks don’t need to be seen in any particular hot-spot. They are, in effect, their own scene and almost seem to prefer the exclusiveness of an “open house.” There are three or four different places – owned by people in the group – where you can walk in on any given night and expect a party. That might mean walking in with a bottle of Bordeaux and playing dominoes at Pichi’s house with Benicio Del Toro or Juanes. Or showing up to an artist’s studio and spending the whole night watching 1960’s Mexican music videos projected on walls while dancing with the beautiful Yoindra Perez and roasting a pig.

When we did go out, the places to be were La Zorra y El Cuervo, maybe the Tropicana on a misty night with its six-tier stage, el Emperador in the Fosca building, or Tondes de Vallanueva where Renaldo my cigar roller works.

PM: How do they earn their living? Is everything linked to the cash and the things that are sent by the expatriates in Miami?

MD: How does any artist anywhere earn his or her living? You create, spread the word, and rub elbows with the right people, right?

You know, these are just like any other artists. Dancers might work for the government’s contemporary dance company, but other than that, these people do like any other independent artist in their field. Painters and photographers have studios in Havana, but sell and exhibit all over the world. The elusive K’cho has pieces in the MOMA in New York. Roberto Fabelo exhibits in global arts shows. The beautiful 20-year-old painter Rachel Valdez – who’s featured on the cover of “Habana Libre” – is studying in Barcelona at the moment – she just had a solo show in Havana and has a show in New York next week. And the same goes for filmmakers – they get funding from, say, Mexico or Spain and place films in festivals from Sundance to Cannes.

Remember that Fidel Castro has always been an exponent of the arts. It’s just like Cuba’s baseball team – these are the people that he wants to be the face of the country. These are the folks for whom travel-bans don’t apply; they’re the ambassadors that Cuba sends out into the world.

PM: The cuban socialist elite has always exist. Is the big change that now they don't mind being seen and known as they are? Why did it change now?

MD: What you describe as the “socialist elite” is a purely political manifestation. Yes, since the revolution it’s always existed and, yes, it is, by definition, it’s own farandula – but this and the artists’ sect I photographed are mutually exclusive groups. They – the politicos – I’m sure they have their own meeting places, their own members, their own style but, frankly, I wasn’t really interested.

As for the artists I photographed, I’m not really sure why they’re finally comfortable with being seen outside of Cuba. I think it’s partially situational. I’m not a National Geographic stringer trying to make a documentary, so I was able to gain their trust from the inside. I knew who they were and they knew my work – I’m sure that helped.

Also, there’s the fact that Cuba itself is changing. Cubans can have cell phones and run small businesses and sell their homes. Starting next week, they can begin to own property too. Talk about a metaphor for change – in a week’s time Cuban citizen will literally be buying back pieces of the island from the government. The regime’s tight restrictions are lessening and maybe these artists recognized that and saw my project as I saw it: as a chance to capture a culture and a way of life on the cusp of change, at a turning point in history. Cuba will never be the same again – I was lucky to capture it when I did.

PM: How do Alex Castro and Camilo Guevara live? Where? How do they earn their living? Did they impose you their own terms for your shootings? and publications? Where did the shoots take place?

MD: A lot of people I talk to about the project get caught-up in name-recognition and I try to right them on a couple points related to Alex and Camilo. Firstly, they’re by no means the epicenter of this farandula. If anything, they’re in the fringes and loosely associated with the group. Both Che and Fidel Castro had other children – I was only interested in photographing Alex and Camilo, as both are also photographers. They fit into one of the missions of the book, which is to explore the creative class of the island.

Secondly, there’s an idea that, because they’re literally the “sons of the revolution,” these guys must live in opulent flats, have servants, etc. – which is categorically false. Alex and Camilo basically live like every other photographer in Havana – which is basically. On one of my return trips to Cuba, we exchanged gifts. Alex and I swapped some hard to come by books and I gave Camilo a tripod, which isn’t the easiest thing to track down in Cuba.

As for access, there were no issues, no restrictions, no requests – not during shooting or during interviews. The shoots were like a photographic jam session after we got acquainted. I photographed Camilo and Alex at will; Camilo and Alex photographed me at will. If you didn’t know their respective surnames, you might mistake us for any three photogs playing-around. We met in hotel lounges, in a friend’s house, in cafés and restaurants – just like I did with many of the book’s other subjects.

PM: Are all the people we meet in your book exclusively heirs of the system's executive elite?

MD: If by “heirs” you mean the literal successors or children, then no. As I said, the political and the artistic factions of Cuba wouldn’t form but the slightest overlap in a venn diagram. If, however, you’re asking if these artists benefit from the stances of the government, I’d say that’s a more appropriate – if not entirely accurate – assumption. Cuba is a place where social connections trump politics, status or wealth - and it's a country that looks after its artists. So, you can deduce that a well-connected artist in Cuba is going to court certain privileges.

But don’t all talented artists court privilege in one way or another? During this project, I went to countless parties with some of the world’s more inspired artists, saw a culture my country embargoes, and had unannounced Cuban beauties appearing on my terrace in the moonlight. Am I privileged, or do I just have, as you say, le cul bordé de nouilles?

PM: How do they deal with the « other » Cuba? with the Cubans that live in much more modest conditions? Do they mind those social differences? And you, how did you feel about that?

MD: Well, by our standards – American standards or European standards – these artists themselves are living in “modest conditions.” Even the most well-off painters or filmmakers in this group don’t have anywhere near the rank of luxury or wealth you’d expect to be aligned with the notion of “success.” The gap between the haves and have-nots in Cuba isn’t the chasm to which we’re accustomed and that makes its hard for us to conceptualize what really constitutes “wealth” in a poor nation. (Just as we have trouble qualifying the terms of poverty in wealthy nations.) I think a lot of people would be surprised by how “well off” Cubans live. Do they have it better than some? Yes. Are they living like Saudi princes? Hardly.

The whole notion of the book depicting “a privileged class in a classless society” leaves a sour taste in some mouths, but of course there are stories that belie that impression. The artists René Francisco is a good example – he’s single-handedly building a school in his hometown. There’s really no charity-mechanism in Cuba and here he is selling paintings outside the country, buying materials with the money and building a school without any assistance.

I can’t really speak to my own impressions on any Cuban inequality as I spent almost all my time in Havana. I wouldn’t want to extrapolate that into a judgment of the entire island. Again, I’ll let National Geographic handle that business.

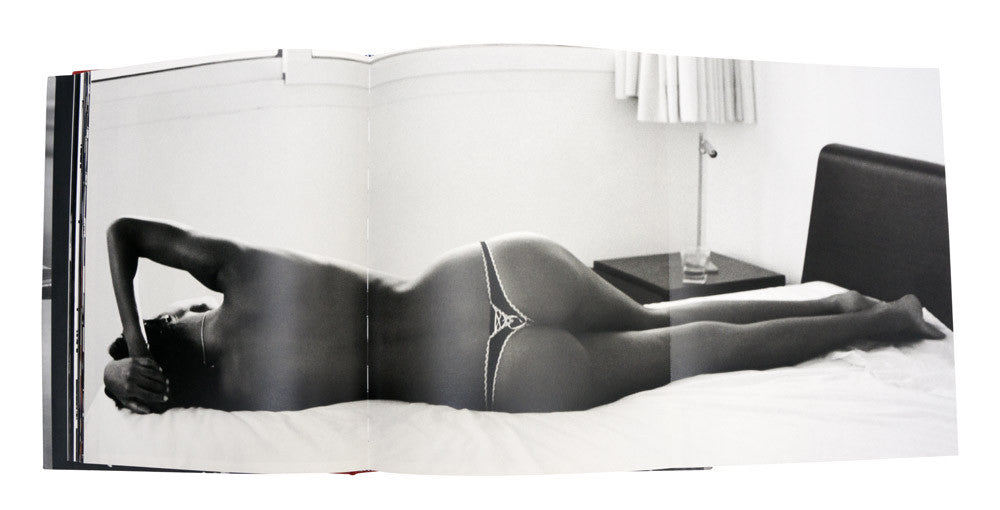

I stand by the book as an artistic impression of a group of people and their setting – a sensual and participatory account of one group of friends in a changing Cuba. It’s not an almanac or a UN humanitarian report. Any social commentary is microcosmic: the allegory of a worldly paradise beset by threats from without and by new hierarchies from within. I can dissect each photo and concoct a thesis, but that was never the point. “Habana Libre” is a narrative project as much about seduction as anything else. It’s a film in stills about the sensual curve of a woman’s side when she waits in bed for her lover and how, in the right light, it might resemble the southern coastline of her country.

PM: Could you tell us the story of a typical night out in Havana?

MD: A typical night out would come after a typical day out – so basically, I would shoot from 8 a.m. to 9 p.m. and then go out again with my cameras to wherever the PMM text indicated. On an average night, we’d start with drinks at someone’s studio, have dinner at a different artist’s house, then maybe catch a set at a jazz club like La Zorra y el Cuervo, go hear Kelvis play at Don Cangrejo, see a show at the Karl Marx Theatre. Some nights I’d run loose down Avenue de Presidente, right in front of my apartment, and just watch the groups of kids ‘til 4 a.m. – 50,000 of them on a 25-block stretch, mostly 14-15 year-olds who form their own mini-farandulas on different street corners. Musicians. Magicians. Skateboarders. Fashion kids. Or I’d just follow my camera and end up where the beautiful women ended up: with lovers on the Malecon, in a club, a stalled elevator, a terrace or the back seat of a car.

But, yeah, I think the best parts were hanging out in the artists’ homes – you never knew who was going to come in or what was going to happen. Just show up with a bottle of rum and an open mind and the night does the rest… And that’s how I imagine the famed Parisian salons in the 1930’s – a writer would come in and, after a conversation, you realize you’ve read two of his books. Same with a filmmaker – “Oh, I know him because he won an Oscar for…” There’s a woman who looks familiar. Of course! You saw her in Pavel’s film “Flash.” Kelvis is writing a film score with Lester Hamlet while Pablo Milanes’ son plays along on piano. When they’re done, they’ll all run out and shoot the scene they just scored.

It was an amazing thing to see – even more amazing to photograph. And it happened every night – ‘til 3 a.m. Then it was time to roll home, have a cigar on the veranda and tuck in for three hours of sleep.

PM: Who are the persons that most impressed you in Cuba? Why Rachel is she your muse?

MD: René Francisco is one, for sure. I mentioned his charity work earlier. His gratitude for his talent and his attempt to give back to his community without looking for any recognition is an inspiration. You get the feeling that Rene’s work is very personal to him, as art should be.

As for Rachel Valdez, from the moment I first photographed her, I knew she had something special – some seductive charm, a glance that grasped out for pleasure. She just intuitively understands her body and how to move to achieve some perfect, intangible effect in a photo - sensuality and a playful type of candor. It wasn’t until after I started photographing her that I learned she was a wonderful painter – and when I saw her work it made total sense. Her control of form is the same on the canvas – breathtaking and evocative, tantalizing and vexing. Slowly, she became something of an unconscious muse, the running thread of the project like some gorgeous personification of Cuba with a raw self-aware sensuality that glued everything together. She was the book’s respiration.

PM: We know that prostitution is very common in Cuba. Even in the upscale social circles of the country. Do the glamorous and sexy creatures that you shot resort of that activity?

MD: I see you’re a man who’s had his share of fun in Cuba’s “upscale social circles.” So you know how things work. Even if you’re not dealing with prostitutes, a beautiful woman has never been at a disadvantage in the company of an older man with money, right?

In reality, I’ve been asked this question before and always fall back on the same reply: If these photos were shot in Paris, Leeds, San Francisco, wherever else – would anyone ask if the subjects were prostitutes? When I photographed beautiful women in Montauk, Tokyo, Barcelona, Fez – no one asked me that.

PM: Did you have a response from the Cuban Authorities after the publication?

MD: There hasn’t been an official response from the government, but I do have an exhibition in Havana in February 2012 – what will be one of the first exhibitions for a living American artist at the Fototeca de Cuba since the revolution.

I think that’s a good sign. If Cuba doesn’t like you, you usually don’t get those opportunities. They’re not shy about that stuff.

PM: Did you have news from Alex Castro and Camilo Guevara? And from the others?

MD: I stay in touch with several of the subjects from the book - Rachel, especially. She’s having a show in New York, as I said, and we have plans to collaborate on something for my next project in Paris.

The Cuba-related news I’m hearing is pretty much the same news you get from the papers – the things I mentioned earlier. People can sell their cars and homes and open businesses. Obama’s allowing Americans to transfer more money to the island. These are relatively small changes, but on an island that hasn’t really changed since 1959, they amount to a lot – another reason I’m glad I was able to get in there and work when I did. Who knows what Havana – or this farnadula - will look like in another five years.

PM: How many trips did you take? When and how long was the first one? How did you decide you were going to do that?

MD: I took eight trips to Havana over 14 months, the first of which was in March, 2009, and lasted a long week.

I can’t really articulate the reason for the decision. It’d be like trying to definitively explain why I prefer steak to chicken or, better yet, a brunette to a blonde. It’s a matter of taste, attraction, flavor.

I knew I wanted to photograph Cuba emotionally, but it took time to understand what that meant to me. Cuba, since the revolution, has come to represent some semi-dormant danger to America. Of course, there’s more to it than that – but, yes, mystery and danger’s part of it. And, to a person like myself, allure comes hand-in-hand with danger. There’s an edge there too – like that which gives film noir its mysterious tow. I tend think in cinematic terms and that’s the vibe I came to feel from the island: something from the shadows of Billy Wilder’s “Sunset Boulevard,” the lure of Louis Brunel’s “Belle du Jour,” the lush filters of Claude LeLouch’s “Un Home et Un Femme.” There’s danger, but there’s also sensuality, beauty and singular charm. That was my idea of the island and I knew if I could just get down there and point a camera around, something would come of it. Call it intuition, I guess.

It’s like the “typical night” I described earlier. You jump into the mix and you see where it takes you. With my previous works, everything was very premeditated – not always staged, but framed out in a certain regard. And that works for some projects, but, you know, you can only spend so much time in the driver’s seat before the back seat starts looking tempting.

PM: What is your best memory in Cuba?

MD: I guess the most vivid and enjoyable memory would have to be that first night I described earlier, the one where I saw the farandula in action for the first time.

You have these ideas about a place or a population – for Cuba it was that sensuality and beauty and charm – and to see all of that flood toward you when you walk into a room, it’s like a fight scene in a film where everything is slowed-down to let your mind catch-up. Maybe a love-scene is a better analogy – it’s steamy and pulsing and seemingly choreographed all to push toward some arousing effect in its audience; to make you feel like you’re there. Except in this case, of course, I was there.

I swear that night is going to ruin every party I go to for the rest of my life. It set this standard for first impressions that will never be topped.

Meeting the sons of Fidel and Che was surreal. Working with Rachel and some of the other beautiful women was amazing. But I don’t think anything will top that first glimpse – that revelation that, yes, there is joy in Cuba. You wink at it and it winks back.

Artinfo interview with Michael Dweck

Artinfo interview with Michael Dweck

Artinfo: How did this show come about? Did you have an initial interest in Cuban society as a subject, or did you stumble into it?

Michael Dweck: I suppose I stumbled onto the subject matter: the “farandula,” the parties, etcetera, but, you can't really stumble into Cuban society — not as an American. But I knew I wanted to go to Cuba for a while — there's a draw to the island I can't really describe, some kind of dangerous and sensual beauty. And there's also the factor I've mentioned before: "There's something going on here that people have no idea about."

When my friends asked about the first trip — the reasons for it — I told them "I'm going fishing," as a joke, but the joke became the truth. I spend a lot of time out in Montauk and I love to fish, but even the best fishermen in the world will tell you that there's a lot of guesswork to the sport. And that became the apparent tie — the realization that, in some cases, all you can do is do the prep work. In the case of photographing in Cuba, that meant having the Visas, the lenses, and the right mindset: "I'll talk to whoever I need to get to the bottom of something." It sounds easy when I talk about it now, but it took a lot of humility in a sense to go to this tiny, insular country as a true "outsider" and try to sneak up on beauty, truth....

I guess it snuck up on me, as much as I hunted it down. It took the bait, if you will, but not in a sinister way. And the end result was the body of work I shoot for — something in which each photograph stands on its own but also contributes to a larger spirit that informs the body's overarching narrative. Here the final narrative depicted a privileged world unknown in the West and still unacknowledged within Cuba.

Artinfo: Since the show has traveled internationally, how does showing it in Cuba affect the meaning of the photographs?

Michael Dweck: That's a good question. I'm not sure I have a good answer though. I always find it interesting to see how people react to my exhibitions, but this was definitely the show I worried about the most, given the subject matter and the audiences.

On one hand, you have domestic reactions from people who have been told what I've been told — the Cold War rhetoric about Cuba being an evil, unhappy island; a police state. How would these people react to images of Cuba in celebration? And what about the Cubans themselves? How would they feel about the glitz that surrounds the group depicted? It was never my intention to showcase the "rules" or "exceptions" of Cuba — but would this come through?

The answers have been reassuring. American audiences, for the most part, have received the project for what it is: a document (but not documentary) reflecting a privileged class of people in a classless society. They seem to have been able to understand the political nuances, without letting that corrupt the humanity and depth of the portraits.

As for the Cuban reaction — that's been phenomenal. The opening attracted a record 2,300 people to the Fototeca de Cuba Museum, and the reception's atmosphere mirrored the reception of the work. Cubans welcomed it as what it was: an honest look into a world both foreign and local that offers escape, potential and maybe a wink of irony. And that's all it was supposed to be.

Artinfo: Are there any political tensions surrounding the making and showing of this body of work, either from the Cuban or American side?

Michael Dweck: The short answer is "no." The long answer is "not really." No, Cuba was great about everything — the government, I mean. Even before I knew the full scope of the project, the officials I worked with were very forthcoming and welcoming. They set me up with all the papers I needed, the visas, etc.

The artists I photographed were a little more reticent at first — as well they should have been. Americans with cameras haven't always gone to the island with objectivity — much less art — in mind. But once I hung around for a while and made the details of the project known, they were very kind and receptive.

I think they understood that the point of my art ran parallel with theirs — in that it had the potential of exposing certain truths about Cuba to the rest of the world. I've said before that Cuba's artists serve as ambassadors for a country that needs ambassadors more than anything. And that tugs on the book's political pant leg... the one that doesn’t depict people moving about cocktail parties, but moving "around" political ones.

That ties to the only tensions that I encountered in the US — the large ex-pat community, especially that in Miami. There are misguided individuals among them who have accused the book of being "pro-Castro," to which I counter, "It's not pro-Castro, it's pro-Cuba." I try to explain to them that you can have pride in a country — or at least, concern for it — without having pride in its leadership. (If you hung a flag after 9/11, you may know the feeling.)

I think "Habana Libre" is for them — the ex-pats in Miami — as much as it's for the Cubans in Havana, or the Americans in Washington: it's about being mature enough to put aside prejudice and the past and see things as they truly exist… whether you like it or not.

Artinfo: The participation of figures like Alex Castro and Camilo Guevara makes your work inextricably linked to Cuban and American politics, yet the photographs present a group of people that seem to come and go, and live life without restraint from the government. What impact does the "farandula" have on Cuba's political present and future?

Michael Dweck: I’m not sure you can separate the impact the "farandula" has on government from the impact of the government on the "farandula," you know?

For starters, this scene exists — the art scene and the celebration within it — because Castro allows it. He's a self-proclaimed patron of the arts as much as he's a fan of baseball or a proponent of medicine. For him, having a vibrant art scene is essential to have a vibrant population — and that's why these artists receive the considerations they do. That's why they're allowed to travel freely and the like. As I said, they're the ambassadors.

That said, this isn't 1959 anymore. The increasing ease of communication and travel has led to a certain global community and that's going to be felt everywhere — even in countries where communication and travel is difficult. That's where these artists come in. They show the rest of the world Cuba and they show Cuba the rest of the world. It moves slowly, but it moves surely, and while they may not be frontline activists, they're helping to inform Cuba's evolving 21st century policy.

In the last year, we've seen increasing freedoms granted in regard to travel, home sales, business creation, money transfers… Sure, part of it is that the country's functionally broke and not receiving the foreign aid it once had. But I believe the soul of the artist contributes, as it does anywhere.

Artinfo: You make life in Havana look absolutely decadent — sexy and full of the leisure afforded only by privilege, money, and youth. However, if "Habana Libre" depicts "the other" Cuba, it must have been hard to avoid the rest of the populace that doesn't feature in the book. What else did you experience in Cuba, which affected your work and made an impact on you?

Michael Dweck: I don't think I made a conscious effort to "avoid the rest of the populace that doesn’t feature in the book." I made artistic decisions about the book's subject and held my focus.

I think it's important to remember that "Habana Libre" doesn't depict Cuba, nor Havana, but a group of people in the city, in the country — my ideal vision. It's no different than the photographs that come out of Fashion Week in New York. They depict a very small subset of a very large and complex society. When publishing photographs of a model on a catwalk, the photographer doesn't have a responsibility to juxtapose them with images of impoverished children in the South Bronx or remind the audience that to get to the shoot, he or she had to share a subway car with a homeless man who soiled his pants. It's the same city, but a different focus.

Cuba is a diverse place with no shortage of suffering and poverty. I’m not pretending that it's not, but I'm also not presenting that as my thesis. When the Cultural Ministers open the doors for a National Geographic crew, they can field those questions. I went to Cuba with long and short lenses, but I aimed them very carefully.

Artinfo: Now that you've left Havana, what projects do you have coming up?

Michael Dweck: I’m working on a tantalizing project called "Checks and Balances" featuring candid shots of "pro-family" US Congressmen engaged in extramarital affairs. No. That's a joke (though it's not a bad idea… plenty of material for fodder).

If you know me, you know my next move is dependent on the prior move — like I described before about my arrival in Cuba. You can see the process in all my work. I pick settings, set-up the cameras, then I zoom-in on elements of note. With Montauk, it was Island — Beach — Youth. With Mermaids, it was Water — Impressionism — Female Form. All I can do is give you a hint of the next keywords floating around in my head: Film. Paris. Growth. Now you know as much as I do.

Indagare interview with Michael Dweck by Simone Girner

Indagare interview with Michael Dweck by Simone Girner

Indagare: What first brought you to Cuba and what were you initial impressions? What would you say is the biggest misconception Americans have about Cuba?

Michael Dweck: I’d had ideas about working in Havana for a long time – though I didn’t know the scope or the focus until I got there and started poking around and making connections. I knew I wanted to photograph the island emotionally, but what that meant, I wasn’t really sure.

I knew I had to go, though. Doesn’t everyone want to go? Here’s a place that’s always been painted as dangerous and sensual; a country that my government denotes as “off-limits.” Well anytime you dangle something in front of an artist that’s risky and seductive and supposedly forbidden – it’s only a matter of time before the artist bites – before anyone bites. It’s human nature to want what you can’t have and, I suppose, artists’ nature to find a way to approach that and synthesize it.

I think that method really allowed “Habana Libre” to sneak in the backdoor, so to speak; to break down some of those misconceptions you mention: it depicts an overall joy that permeates Cuban life, in spite of the government; and it depicts artists leading fine lifestyles thanks, in part, to the support of the same government.

Indagare: How has the country changed since your first visit?

MD: The most significant changes have actually come since my last visit. A lot has loosened in recent months: Cubans are allowed to have cell phones. The government has issued 390,000 small business licenses. You can sell your house or own property.

One of the best examples is the woman who I met when I was in Havana. She’s making 20-cents a day as the assistant director of a contemporary arts gallery, and now she owns a house that can be sold for $1.2 million. How do even begin to understand the implications of that?

Beyond that, the island’s also seeing some new construction. Golf courses and hotels are slowly being restored. The government is obviously short on money and they seem to be making capitalistic concession, which is good and bad, depending on how you look at it. There will be more money coming in eventually, but at what cost? Already, some of the under-the-radar clubs I’d visited have been overtaken by tourists. It all kind of goes against the ideals of the revolution, but money is money, I guess.

I had a feeling that something like this was going to happen, which was another reason I made the first trip. And I’m I got there when I did. If I’d waited even a year or two, it would be a much different scene; a much different book.

Indagare: Were people welcoming to you taking their picture when you first started shooting in Cuba?

MD: Once the artists knew who I was – once they knew I wasn’t just some joker with a nice camera – they were very welcoming. It helped that we shared some common ground and that, in some cases, we were familiar with one another’s work. Without that I would never have gotten the access I had.

This isn’t DisneyLand – it’s illegal to photograph in most places without approval. So, if you make it to Havana, don’t expect to be able to go into a nightclub or a café or an artist’s studio and start snapping photos. I’m sorry, but “Michael was allowed to do it,” isn’t going to fly there.

Indagare: Your book is divided into sections, eg models, cars, art, etc. Did you chose to photograph these separate subjects, or did you notice your themes as you were compiling the works for this book?

MD: I had themes in mind, but conceptualized them more so as “scenes” – as in a film. That’s part of what makes the book unique – I tried to direct a narrative thread that carries the reader through the work. It’s similar to what I did in “Montauk: The End” – and there aren’t many art books like this. Maybe “Cowboy Kate,” but outside of that, the nearest examples are in cinema.

The flow is chronological and fluctuates between the nocturnal and the diurnal: You’re in a nightclub; then it’s the next day at a concert, an amusement park; a party at an artist’s studio at one a.m.; the backseat of a convertible; The Tropicana the next night; you’re driving on the highway when your car breaks down; you’re at the beach; you’re beside a pair of lovers in an abandoned elevator; you’re on Avenue de Presidente with 50,000 teenagers on a Saturday night. The whole thing plays out like the stills of a sensual trip through these elite circles in Cuba. It’s like a movie on paper in a dream.

Indagare: What do you miss from home when you are traveling?

MD: What do I miss? I miss my family. I miss speaking English. I miss the conveniences, the predictability, the internet access. I missed everything that I’ll take for granted again when I’m back home and begin missing what I’d wasted my time resenting. And that’s what I tried to remind myself every time I went back to Havana: Just go with it and enjoy where you are and what that means.

There’s something charming about the isolation too. Sure, I wish there was wifi or 4G, but there’s also something priceless about relaxing and smoking a cigar on a terrace overlooking the Malecon without constantly feeling compelled to check my email every eight minutes. After all, you can’t really appreciate something for what it is if you’re hung up on what it’s not. Luxury is a relative term and only a fool tries to escape a place with the hopes of it following him.

Indagare: Do you have a favorite Cuban artist? What limitations do Cuban artists have in selling their work to American collectors?

MD: I have a few favorites. Carlos Quintana is probably my favorite contemporary Cuban painter. Then there’s Rachel Valdes – she’s featured on the cover of “Habana Libre.” She’s only 20-years-old, but her paintings are phenomenal… you’ll be seeing a lot more of her in years to come. Traditionally speaking, I’d have to go with Wilfredo Lam – his style wanders from cubism to surrealism and should be up there alongside Picasso. He has a museum in Cuba where I wanted to have an upcoming exhibition – they don’t show contemporary work, though, so it’ll be at Fototeca de Cuba.

I’m not aware of any complications that a buyer or seller wouldn’t encounter in an art transaction in any other country. You, as a buyer, need to get a permit - which will take 20 minutes - and then you’re all set to take art home. It’s the same as Italy or Mexico – they want to inspect the purchase, make sure it’s not from antiquity; make sure they’re collecting all due taxes. But there’s no issue for the artists. They’re free to exhibit outside of Cuba as well.

Indagare: Have you ever visited anyplace that felt like Cuba or is the country totally unique in the world?

MD: I think every place is unique, but Cuba’s singularity takes things a step-further as the originality is cultural, geographical and, in ways, generational.

Until recently, Cuba was pretty much the exact same country it had been since the revolution in ’59. The buildings and cars haven’t changed, the government hasn’t changed, the society hasn’t really been influenced by outside media. It’s like Pompeii after Vesuvius erupted. Everything seems preserved from some lost moment of impact.

Prior the revolution, though, there was a lot of foreign money pouring into the country, which accounts for the surprisingly durable infrastructure. The water is drinkable from the tap – there are roads there that seem better maintained than the Long Island Expressway. But, yeah, the nostalgic element of the island underscores everything, as does the unavoidable existence of Fidel’s regime. Those are inescapable realities that make Cuba remarkable in all definitions of the word.

Indagare: Cuba has a vibrant urban culture but no widely available internet. Is this a shock when you first visit? Do you notice this instantly when visiting?

MD: Well, you could make the case – like I said before – that this vibrant culture is precisely because there is no internet, no outside influence. That explains the societal quirks, but, you’re right – there is a surprising amount of communication and interconnectivity despite the lack of internet and high price of modern, technological contact.

I like to use the example of the recent Peace Without Borders concert held in Revolution Square in Septembet 2009. This was the country’s first big outdoor concert and they were expecting more than a million people, but in the days leading up to the concert, no one knew when it was. There were no posters or commercials like we would have. Even the sound engineer didn’t know when it was. I asked Juanes who was the featured performer, and he wasn’t sure. But somehow, people found out. At midnight that Friday, I heard people coursing through the streets and the next day there’s 1.5 million people in the square for the start of the show. It’s an old-school system of communication – how life worked before cell phones and email. And, what’s odd, in many ways it’s more efficient than our modern methods, because it boils down information into necessity, it forces people to rely on one another and it makes us interact face to face in ways Facebook never will.

Indagare: Which artists influence/inspire you?

MD: It really depends on the body of work. For the “Mermaids” series, I was moved by the French impressionists – Monet in particular.

For “Habana Libre,” as I mentioned before, I thought of scenes in more cinematic terms, so I found myself looking to filmmakers for inspiration. I really like Billy Wilder, the aesthetics he played with in “Double Indemnity” and “Sunset Boulevard.” Or some of the French masters, Louis Brunel’s “Belle du Jour,” Claude LeLouch’s “Un Home et Un Femme.” The vibes David Lynch brought to “Blue Velvet” or “Wild at Heart.”

I’m thinking of shooting a film in future – something in Paris maybe – and a lot of the classic noir motifs keep coming fogging up my mind. That’s my problem with inspiration – it gets inside me and I can’t shake it until I’ve re-interpreted it somehow.

Indagare: What are some of your favorite things to do in Havana and elsewhere in Cuba? What should a first-time visitor not miss?

MD: I’ve really only spent time in Havana and Playa Del Este, but my favorites activities are the same anywhere: jazz, dinner with artists and friends, smoking cigars and, in this case, drinking 18-year-old rum on a veranda overlooking the Malecon.

I found Havana a terrific place to bounce around spontaneously. If you know enough Spanish and are willing to have an adventure, you should talk to people, ask around, make friends and see where things take you…

Personally, I would have a Mojito in the back garden of Hotel Nacional. Visit the Partagas Factory to see the best cigars in the world being rolled. There’s a band called Los Kents, which is like a Cuban version of the Rolling Stones – you can catch them in Miramar. Eat in La Guarida, the restaurant featured in the film “Fresa y Chocolate.” Get a grilled lobster at Malecon 107, or some Spanish food at El Templete in Habana Vieja. I’d see the 10 PM show at The Tropicana too. (Some people say it’s touristy, but there’s something amazing about seeing a show that hasn’t changed since 1928. It’s incredibly sexy and timeless.) You should request a table in the front.