Sonya, Poles, Montauk 2002

Sonya, Poles, Montauk 2002  Flag at Snug Harbor, Montauk 2002

Flag at Snug Harbor, Montauk 2002  Adriana at The Panoramic View, Montauk 2002

Adriana at The Panoramic View, Montauk 2002  Surf’s Up, Montauk 2006

Surf’s Up, Montauk 2006  Lilla, Nappeague 2002

Lilla, Nappeague 2002  Old Boards at Tony’s House

Old Boards at Tony’s House  Surfing at Ditch Plains, Montauk 2002

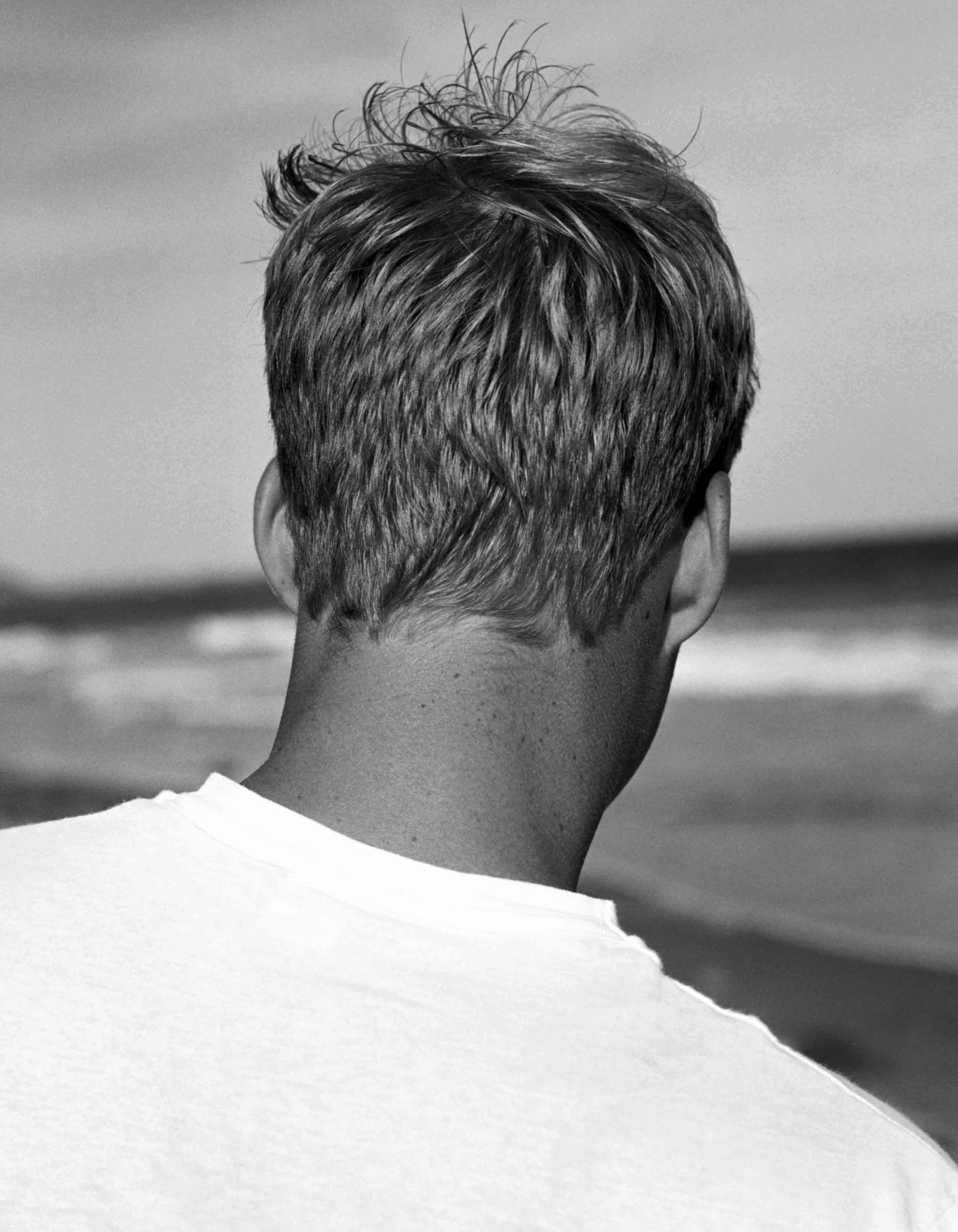

Surfing at Ditch Plains, Montauk 2002  Ray, Montauk 2002

Ray, Montauk 2002  Morning surf at Poles, Montauk 2012

Morning surf at Poles, Montauk 2012  Jessica and Kurt, Montauk 2002

Jessica and Kurt, Montauk 2002  Getting wet, Cavett’s Cove Montauk 2006

Getting wet, Cavett’s Cove Montauk 2006  Laying out, Montauk 2012

Laying out, Montauk 2012  Lilla, Nappeague 2002

Lilla, Nappeague 2002  Wave after the storm, Montauk 2009

Wave after the storm, Montauk 2009  Cooling off, Turtle Cove, Montauk 2012

Cooling off, Turtle Cove, Montauk 2012  Julia and Brittany, Hither Hills/Apres surf, Montauk 2012

Julia and Brittany, Hither Hills/Apres surf, Montauk 2012  Lilla, Nappeague 2002

Lilla, Nappeague 2002  Natalie on the Rocks, Camp Hero, Montauk 2008

Natalie on the Rocks, Camp Hero, Montauk 2008  Surfing Air Force Base, Montauk 2013

Surfing Air Force Base, Montauk 2013  Calm Before the Storm, Montauk 2008

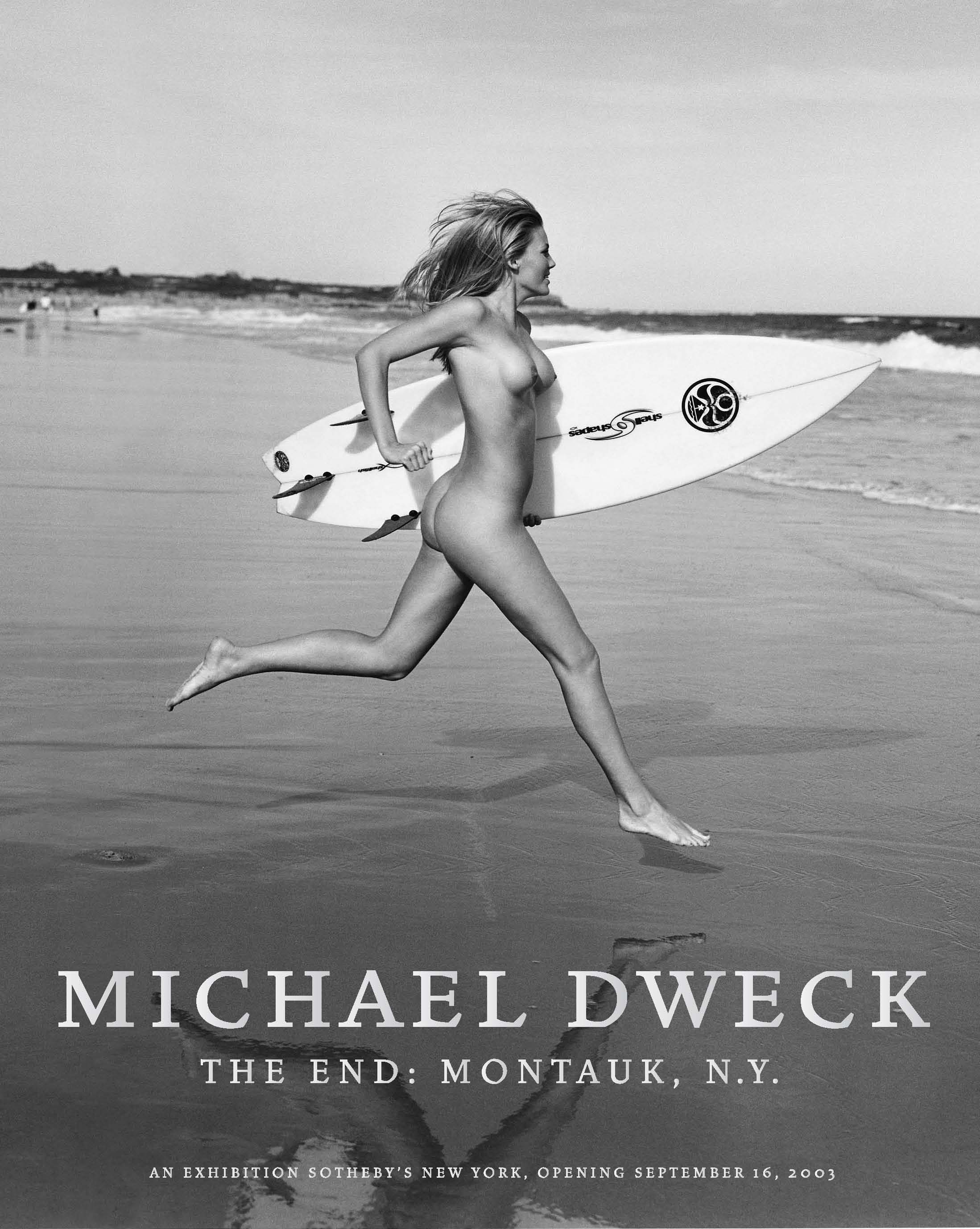

Calm Before the Storm, Montauk 2008  Poster from the Sotheby’s exhibition 2003

Poster from the Sotheby’s exhibition 2003  Sotheby’s exhibition 2003

Sotheby’s exhibition 2003  Sotheby’s exhibition 2003

Sotheby’s exhibition 2003  Sotheby’s exhibition installation 2003

Sotheby’s exhibition installation 2003  Sotheby’s exhibition 2003

Sotheby’s exhibition 2003  Staley Wise exhibition 2012

Staley Wise exhibition 2012  Staley Wise exhibition 2012

Staley Wise exhibition 2012

Michael Dweck The End: Montauk, N.Y

In the 1960s, the fishing village of Montauk became the surfer's paradise of the United States' East Coast. Located as the tip of Long Island's South Fork, the easternmost point of the Hamptons, this paradise existed primarily for locals - not surfers who migrated to the beach for the summer, but those who were out in the rocky reefs every day, year round. Today, a new tribe of surfers exists - a group of young locals who live by their own rules. Rule number 1: Never tell anyone where the good surf spots are. Rule number 2: See rule number 1. In the 1990s, photographer Michael Dweck rented a house on Ditch Plains beach (site of the best surf break) and struck up a friendship with one of the local surfers, eventually gaining uprecedented access to the insular local surf community. Dweck's photographic essay follows the surfers through their daily rituals, from early morning wave reports to evening bonfires on the beach, capturing their youthful hedonism. Through portraits, nudes, and photographs of the landscape, this book celebrates lives lived only to surf, and captures an endless summer of perfect weather and languorous beauty.

Surf Collective Interview with Michael Dweck

Surf Collective

Interview with Michael Dweck

SC: You are a true native and longtime resident of Long Island. You've seen it evolve and change in many ways, especially around Montauk and the areas you pay tribute to in the book. What are your thoughts on the evolution and changes that have occurred since the book's publication in 2004?

MD: It’s funny, because, in ways, that’s the big question I haven’t been able to answer for the last ten years. It’s hard to see something you love change, but at the same time, it’s foolish to pretend everything will stay the same. That conflict was part of the impetus for the original collection when I started conceptualizing it in 2000. I knew Montauk would change, and I wanted to capture some of the sentiment and beauty before it faded – specifically, I wanted to capture the way Montauk made me feel… And I didn’t want to be right here – ten years out from publication – being one of those sentimental, nostalgic people who whine and rant about change, you know? In that way, the collection achieves a lot of what I wanted it to – it freezes Montauk for those who want it frozen, and it lends some insights to those who don’t know what the hell their sentimental neighbors are ranting and whining about.

But I try not to deal in specifics, because I don’t think it’s necessarily an artist’s job to hold vigils (not that I don’t hold a bit of a personal candle for the East Deck and Salivar’s). I just know that I can’t really be objective, so I put the onus on my photographs to honor establishments or condemn developers… Does that make any sense?

SC: As a photographer, you have traveled and explored some of the most beautiful, interesting, and diverse places and locations around the world, but your love and loyalty for New York seems to always remain the same. What is it about New York, for those who many not understand, that lures you back and contributes to being your favorite place in the world?

MD: Well, I don’t think I could leave New York even if I wanted to… I grew up here. This has been my only real home, so you’re kind of adding the natural attraction that everyone feels to NY with the innate attachment that people have to the first place they’ve called home. It’s a tough spell to break.

At the same time, though, you could extrapolate my personal feelings on Montauk to the City, the State, and on and on… 2015 New York is certainly not the place where I grew up. Again, I’m not going to weep over the changes or organize a vigil – but it’s tough seeing your city loose the footholds that once nurtured artists and outsiders and the like. We’re hemorrhaging our creative class, and it’s scary to think that – if I were born today – I might be forced out to Detroit to pursue a career as a visual artist… I dunno… That’s a whole ‘nother conversation.

SC: When you first came up with the idea to publish your iconic book, The End: Montauk, NY, what was your main goal and what has been the most rewarding part of the journey?

MD: Like most of my work, The End: Montauk, N.Y. started as an attempt to build creative walls around a very particular, cloistered scene – its characters, its setting, its lifestyle, etc. – and then, from that, capture an idealized impression on that scene.

So, I didn’t want to be the documentarian that explains a foreign world, nor the insider bragging about his haunts, but rather a filmmaker, in a sense, who actually transports you to new environs, immerses you in a place and time, and tells a story in the process. At that point in time, when I was working on the collection, this type of narrative work wasn’t really being done in fine art – but I knew I couldn’t really do justice to Montauk – both as I knew it and imagined it – without approaching it as something with a plot…

As far as the rewards of the journey – the fact that I’m here reflecting on this work ten years later kind of says it all for me… I never thought The End would go out of print in two weeks, or generate the kind of demand that it has. I especially never thought it would ever become something on this scale – a large-format, signed numbered edition with prints and all that. It’s incredible.

It’s all been incredible, really – I’ve heard from thousands of people who respond to the work, and that’s a huge reward for me. This project was all about making material something that previously had existed in my mind as equal parts memory and reverie… It’s been tremendously meaningful to see so many people respond to the story, the characters and, moreover, the place – Montauk.

The next reward will come when I get to share this with people again… we’re doing some special events in the fall, and an Art Basel event, all leading up to the release of the 10th anniversary limited edition box set of The End. I think that’s when it will really sink in.

SC: Surfing is a main focus in your life and obviously in the book as well. What, in your opinion, differentiates surfing from other sports and activities? Do you think the city's energy and dichotomy between the beach and city life makes it especially different in New York?

MD: I’m not even sure if I can explain it, because it’s not even about the sport, but often what it represents – there’s escapism, balance, and a certain humility (before nature), or that need for adaptation… I don’t know many things in life that test a person – physically and spiritually – like surfing does. I mean, I’ll challenge any golfer who says his or her sport is a better metaphor…

Even as an artist, I’d be lying if I said my approach to my work hasn’t been inspired in some way by surfing. Trying to build a focused body of work – especially a narrative – that’s an endeavor that starts you off in some helpless, chaotic, and confusing places… I mean, you go out there with an idea, and you’re floating around, and you have to paddle and get up, or you’ll end up with a pile of shit… Maybe that’s not the best metaphor, but you get the idea. There’s not a huge margin of error in art, photography, filmmaking, and you have to get your timing and balance down…

As far as the second question – I can’t really compare the sport in NY to anywhere else. Maybe I’m too close to it. I grew up on Long Island, and now, I can see the Hudson from my place in Manhattan, so it’s just part of who I am. I grew up surfing and sailing and fishing. I’m most comfortable when I can stumble to the shore. I can’t imagine growing up on the coast and not feeling that way... I’d venture that that’s the same anywhere.

SC: Although Montauk and the East End has changed as time has progressed, there is undoubtedly still that sense of allure and untouched beauty about it. What are some of the things you still love most about this beach community?

MD: We’re talking about one of those places that just feels different, you know? You don’t have to tell a first-timer that they’re going somewhere special, because they can just get out of the car and feel it. And that’s still there. It’s something intangible – and for that matter ineffable. You can’t explain it, and you can’t erase it. That’s my Montauk: That’s what developers can’t destroy, and tourists can’t tread over… It’s a feeling that you get at Ditch Plains, or talking to a fisherman before a storm, or just staring out at the sea at sunrise. Something about the community, the natural beauty, the lifestyle… See, I can’t even finish my sentences… that’s the feeling.

And that’s the reason for the charitable component of the new book release. We’re giving a portion of the proceeds from each book to protect the ocean and those fragile shores, because of that feeling. If we lose that, we lose so much… How do you rebuild a feeling… something ineffable?

SC: What's up next for you in your career... We know you are working on your first feature film. Can you tell us a bit more about it?

MD: Sure… It’s a full-length doc following two years at The Riverhead Raceway - another endangered Long Island haunt that’s close to my heart. I did a 360-look at all aspects of the place – from the individuals who drive the beat-up old stock cars, to the commercial threats that will eventually shutter the track (which is Long Island's last). I grew up going to the track, so it’s a bit of a personal piece, but there’s also some of the same metaphor you might see in Montauk, or my work in Habana Libre… I’m making a case for endangered identity and underrepresented art… you know, as the shadows of strip malls creep into the frame. I like to describe it as “a David vs. Goliath story, only if David were a tow truck driver and Goliath were a Wal-Mart…”

I’m really excited about it. I did a whole series of abstract pieces that tie in with the film, so it’s kind of a real mixed media project too.

SC: If you could describe your perfect day, what would it consist of?

MD: Art would have to be one component of it… Probably what I call a “click day,” that one day during a project when all the ideas and hopes you have for something kind of click together, and you realize, “Hey, this thing might actually work!” (And I’m sure that happens in a surfer’s career, as much as it does an artist’s…) That’s what keeps so many of us going - when everything falls into place and you feel invincible. Maybe that breakthrough on a big project, followed by drinks and dinner with friends and family? Is that lame? Nevermind – Let’s go with trip to Mars, and dinner with Godard.

SC: You ran a very successful ad agency before you became a successful full-time photographer. What are some of the things that you are most appreciative of now that you can focus on your main passion?

MD: It was always about art. I was just lucky enough to realize – or re-realize – that when I did. I had some trepidation of course, but at the same time, I knew about Warhol and Irving Penn (both art directors in advertising), so I knew it wasn't an impossible jump to make. It's all about sensibilities and instincts. As an artist, you just get to treat those with more sincerity and let them come through as something raw and visceral.

Now, I mean, I appreciate it all. Being able, as I said before, to make real-world versions of ideas – and moreover to have those ideas reach people, and reach minds… That’s the beauty of art – a narrative about a small community of the East End may reach people in a way that an editorial on over-development can’t… I get to work in a medium that provokes and teaches in inexplicable ways. Like Whitman says (another Long Island guy, actually) “I and mine do not convince by arguments, similes, rhymes;/ We convince by our presence.” That, to me, is art.

The fact that I can be part of that… wow.

SC: Who have been some of the biggest professional and personal inspirations in your life?

MD: Again, without getting too specific, I’ll say, anyone (or thing) that’s resilient despite being repressed, adventurous despite being mortal, and creative despite being engineered solely to survive. That could be surfers in Montauk, or poets in Franco’s Spain… There’s no shortage of inspiration if you pay attention.

SC: Is there anywhere else in the world you would live?

MD: Again, I’ve always been interested in the way geography affects culture, and, moreover, how it creates exclusive groups. So I guess I have a running list with that criteria in mind: Africa, Asia, South America, Australia, Europe (again), and, why not, Antarctica.

The Usual Magazine interview with Michael Dweck

The Usual Magazine interview with Michael Dweck

When and how were you first drawn to photography?

I like to say that I was already a photographer before I even knew what photography was... My parents bought me my first camera when I was seven, and at that age, you don't really need to know the names of things to enjoy them or to investigate them. I would photograph on the beach by our house and play around with light and focus. I didn't know the word aperture or anything about lighting. I just knew that photographs looked great at a certain time of day, and that certain angles and actions of people resulted in something moving. There was something almost magical about photography and even the camera itself.

I'd later learn all about composition when I studied architecture then fine art, but at the heart of my passion was that time on the beach when I was discovering it for myself... Because that still informs what I do now more than anything I learned in a classroom or in a book – the magic of discovery.

You worked in advertising as a creative director for years before turning to photography full time. What was the job that pushed you to finally make the career shift?

I wouldn't say that it was the job, or any particular “job” therein that pushed me to shift careers... It was more of a sentiment. I started the company with an intention to do something I hadn't yet defined. After winning a Gold Lion at Cannes and landing a TV piece in the MoMA, I felt like things had defined themselves. And that was pretty much it.

That's the way I usually work – following instincts, rather than goals. Setting a goal keeps me in a maddening little container and sets me up for disappointment. Following a hunch – or some gut instinct – that allows me to explore and judge success in hindsight. And that's what I'm doing now, I guess. We'll see how it work out. [laughs.]

How hard was it to take that leap of faith and pursue your passion?

It was easy to decide, if difficult to execute. It's like deciding you want bouillabaisse for dinner. “Okay – done. I know what I want... now I just have to go to Gosman’s and buy all this seafood, and saffron and spend a couple hours prepping everything...” you know?

It was tough to disassemble that amazing world I built from the ground up and leave all those great people, but – I don't know – I just wanted bouillabaisse. [laughs.]

What qualities do you look for in your subjects?

Again, as with goals, I don't really search out subjects, per se I just happen to be surrounded by them no matter where I am in world – Montauk, NYC, Buenos Aires, Tokyo, Paris, Havana, Borneo [laughs] I think it’s just a matter of being open to find something without necessarily looking for it.

I always liken it to casting a film – something I'm kind of doing at the moment for my next project. If you go into the casting with a person in mind, you'll never be satisfied. If you go in, however, with an idea or a vibe in mind, you can find that in someone – even if he or she doesn't know it's there.

So my ideas or vibes are personal and just below the skin. I like expressive faces and figures still on the verge of knowing what they're expressing; youth that's in migration and struggling with urges, juggling confusion with sexuality.

I ultimately work in suggestion – that's almost my medium more than photography. And to maximize this, I find it best to work with people who have latent qualities that they haven't yet realized and/or exploited.

What is your process like gaining a subject's trust?

I don't know that I have one. I even don't know that I believe that a subject has to truly trust a photographer. When I meet someone I want to work with, I just introduce myself. I explain my work. That's pretty much it. We go from there.

As I said, I usually pick subjects based on naturally observed behavior, so it's not as if I have to woo them to present themselves in one manner or another. I just ask them to be themselves. And even if they're not – not comfortable or natural – that works sometimes too.

It’s a misconception that being a good model or subject is all about being attractive. Sure, that doesn’t hurt, but there has to be more… Complexity, curiosity, confidence, something below the surface that you can’t explain, but can capture in a photograph if you try hard enough.

What stories are you trying to tell through your photography?

It's very subtly hinted at, but all of my work is part of one grand arc about artificial intelligence and the impending technological singularity. [laughs.]

No, my work varies from project to project. With Montauk: The End, the narrative dealt with the idyllic space where youth and beauty are immortal and potential doesn't have an expiration date. Habana Libre had a long-form plot that followed a privileged class of people in a so-called “classless” society, with splinters of hope and potential in there too. Even Mermaids, which was my most abstract body of work, had a story built into its abstractions – a fantasy world below impressionistic waves. And in all of these there’s a recurring idea of suggestion... the interaction between subject and audience that plays out like some kind of elaborate dance. But that's more something elicited than told, I suppose.

You have seemingly endless imagery from Montauk. What is it about the town's people and places that you are so drawn to?

The village and the full-timers represent something beyond appearance – and that's what I love about them. More than any place I've ever lived, you guys understand what it means to be a community, to preserve identity and maintain hope in the face of the constant nonsense that swallows so much of their surroundings. It's a microcosm of the world, in a sense, but it's also a stark departure from it.

As an artist, what would you say are your greatest accomplishments thus far?

I think my most recent work, Habana Libre, was the most difficult and the most satisfying project I've undertaken. I mean, the fact that I was able to do endure eight separate trips to Cuba and come back with a project without getting arrested or falling in love is nothing short of a miracle to me. It required traveling to a location off-limits to most Americans, accessing a group of artists off-limits to most Cubans, and working in conditions too hot and festive for most sane adults. And then going back and becoming the first American contemporary artist to have a solo exhibition in a Cuban Museum – that was overwhelming to say the least.

But I might just be saying that because it’s my most recent project. Before that, I thought I’d never top Mermaids. I shot it mostly at night in the deep rivers of Florida, but it perfectly captured my feelings about the waters off Montauk and the barely-there sirens that call to me from below the surface as I’d fish late into the night.

The End:Montauk, N.Y. will always be a huge accomplishment too. That was my first real project, and one I sat on for years before I found the time to complete it. So, that means a lot for different reasons as well.

Do you have one photo you feel sums up Montauk?

I don't think any photograph can sum up anyplace – be it Montauk, Paris or The Sudan... It's the same with other art – I don't think a song can sum up surf culture, or a movie can sum up The Civil War. Art contributes to the understanding of things, places, people, events... but once artists claims to “explain” or “sum up” anything in whole, they're overstepping their bounds. That's just my opinion.

Do you follow photography trends or look to other photographers for inspiration?

I admire other photographers, for sure. That said, I don't really let their work inspire me necessarily. Maybe their work ethic or their legacies, but not their catalogs.

For inspiration, I look more to film and fine art – impressionist paintings, abstract sculpture, even architecture. I find so much great use of narrative, space and form in other mediums and I let those push the aesthetics of my work more than anything else.

In art, the pursuit of an idea is always more interesting than the conquest. Do you think this also applies to women and the key to what makes your images of women captivating?

I don't think the pursuit is always more interesting than the victory, or whatever... not in art or relationships. I think the former is just a different source of pleasure than the latter and I think it's important to differentiate those from one another. My work – especially in relation to women – deals with seduction or, as you called it, the pursuit phase. It's about insinuation and flirtation, where there's a very elegant and subtle undercurrent that keeps attentions intact. This, of course, strays quite a bit from “the conquest” which is carnal – and though often attractive in its own way – rarely subtle or contained. I try to stay in the wheelhouse – that place where seduction lives and desire has yet to knock.