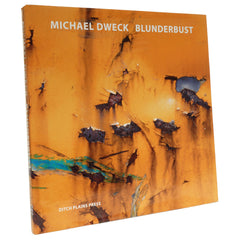

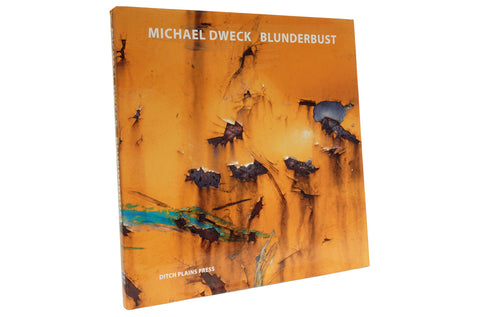

Michael Dweck: BLUNDERBUST

Interviews: TBA

Published by Ditch Plains Press, New York

Release date: 2016

Michael Dweck, Blunderbust

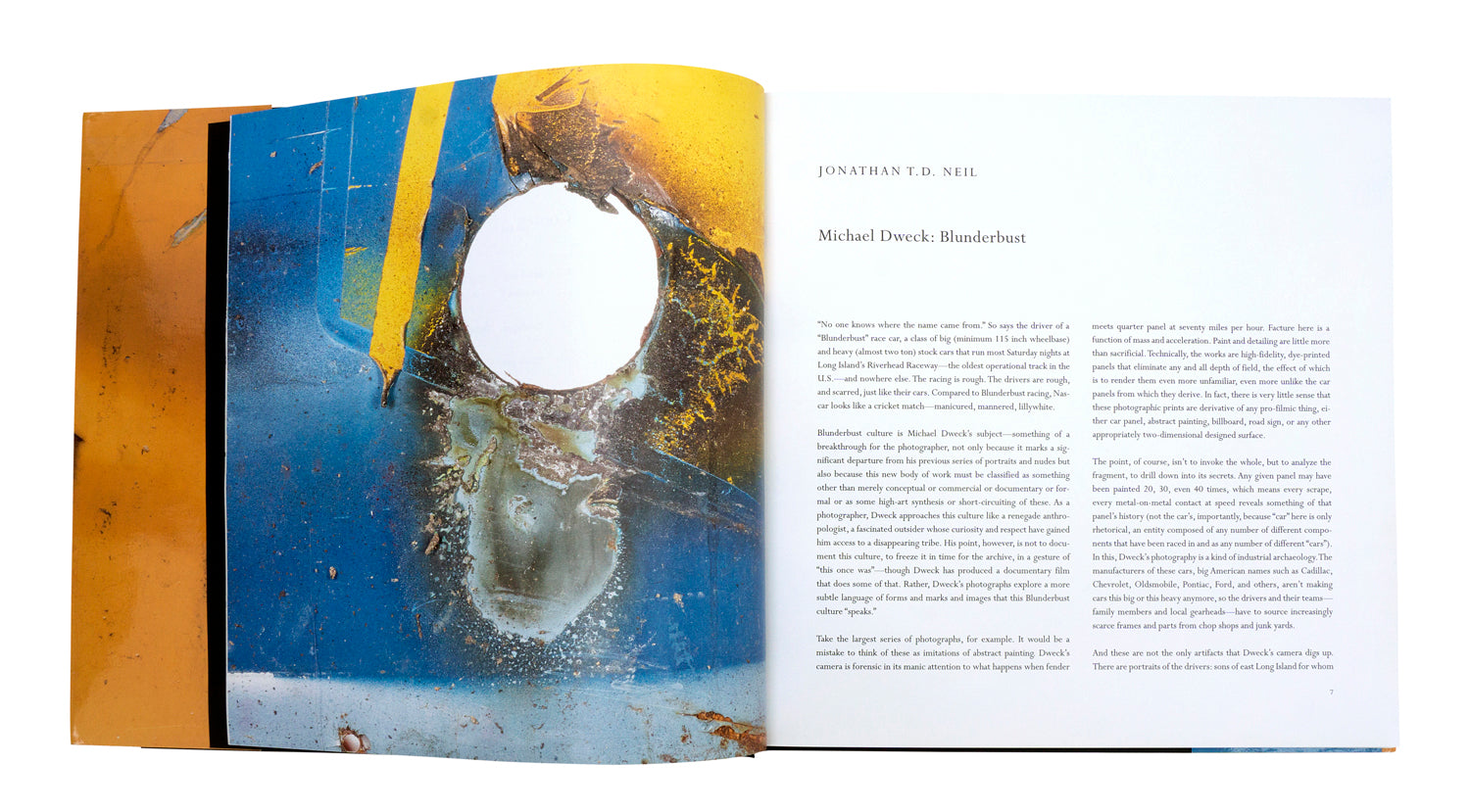

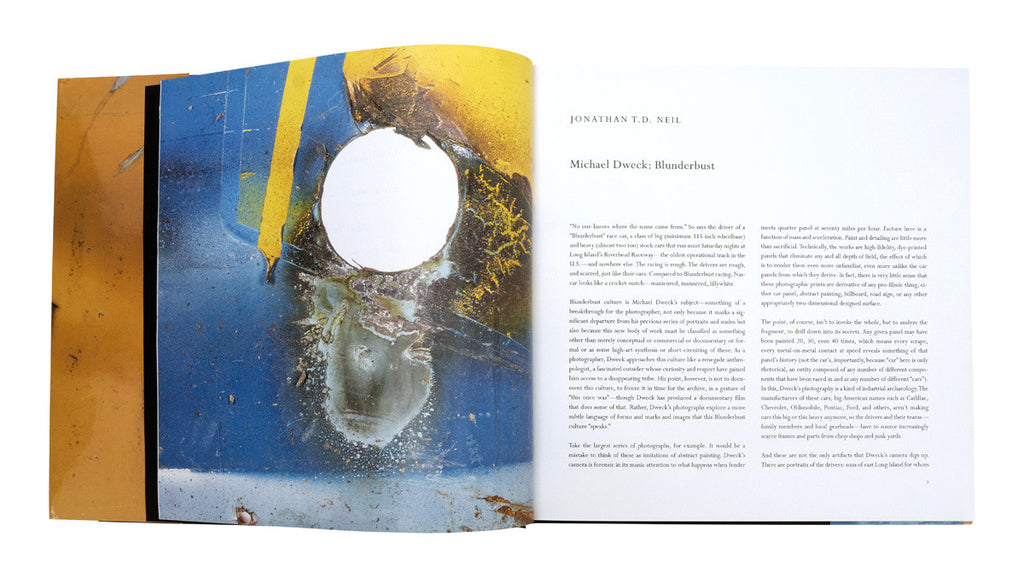

By Jonathan T.D. Neil

“No one knows where the name came from.” So says the driver of a “Blunderbust” race car, a class of big (minimum 115 inch wheelbase) and heavy (almost two ton) stock cars that run most Saturday nights at Long Island’s Riverhead Raceway—the oldest operational track in the U.S.—and nowhere else. The racing is rough. The drivers are rough, and scarred, just like their cars. Compared to Blunderbust racing, Nascar looks like a cricket match—manicured, mannered, lillywhite.

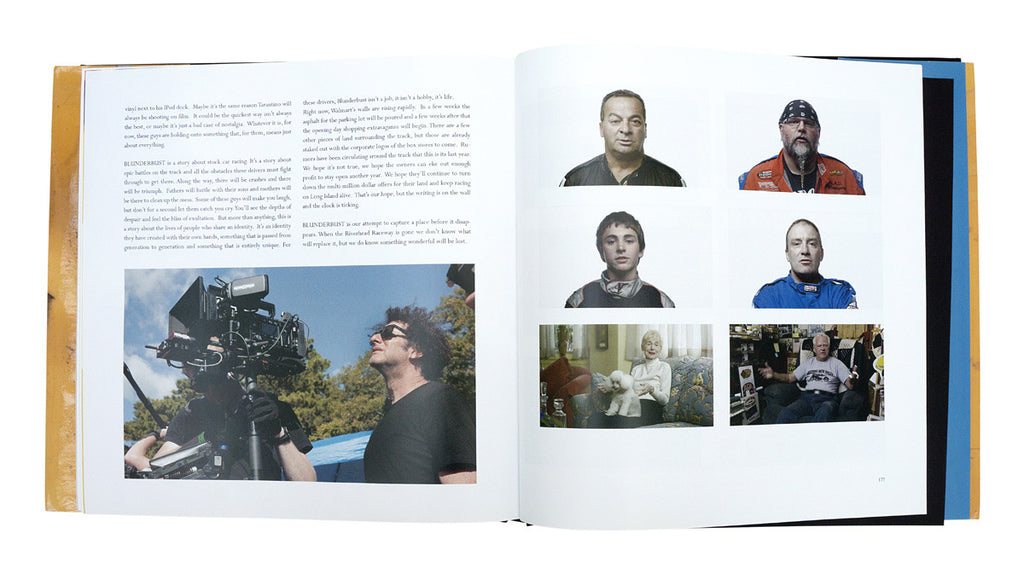

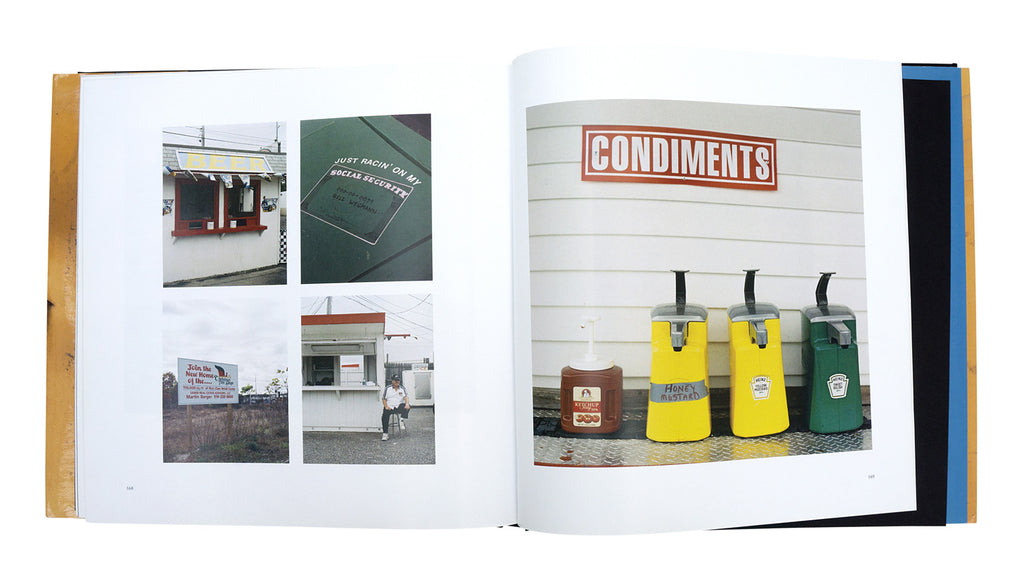

Blunderbust culture is Michael Dweck’s subject—something of a breakthrough for the photographer, not only because it marks a significant departure from his previous series of portraits and nudes but also because this new body of work must be classified as something other than merely conceptual or commercial or documentary or formal or as some high-art synthesis or short-circuiting of these. As a photographer, Dweck approaches this culture like a renegade anthropologist, a fascinated outsider whose curiosity and respect have gained him access to a disappearing tribe. His point, however, is not to document this culture, to freeze it in time for the archive, in a gesture of “this once was”—though Dweck has produced a documentary film that does some of that. Rather, Dweck’s photographs explore a more subtle language of forms and marks and images that this Blunderbust culture “speaks.”

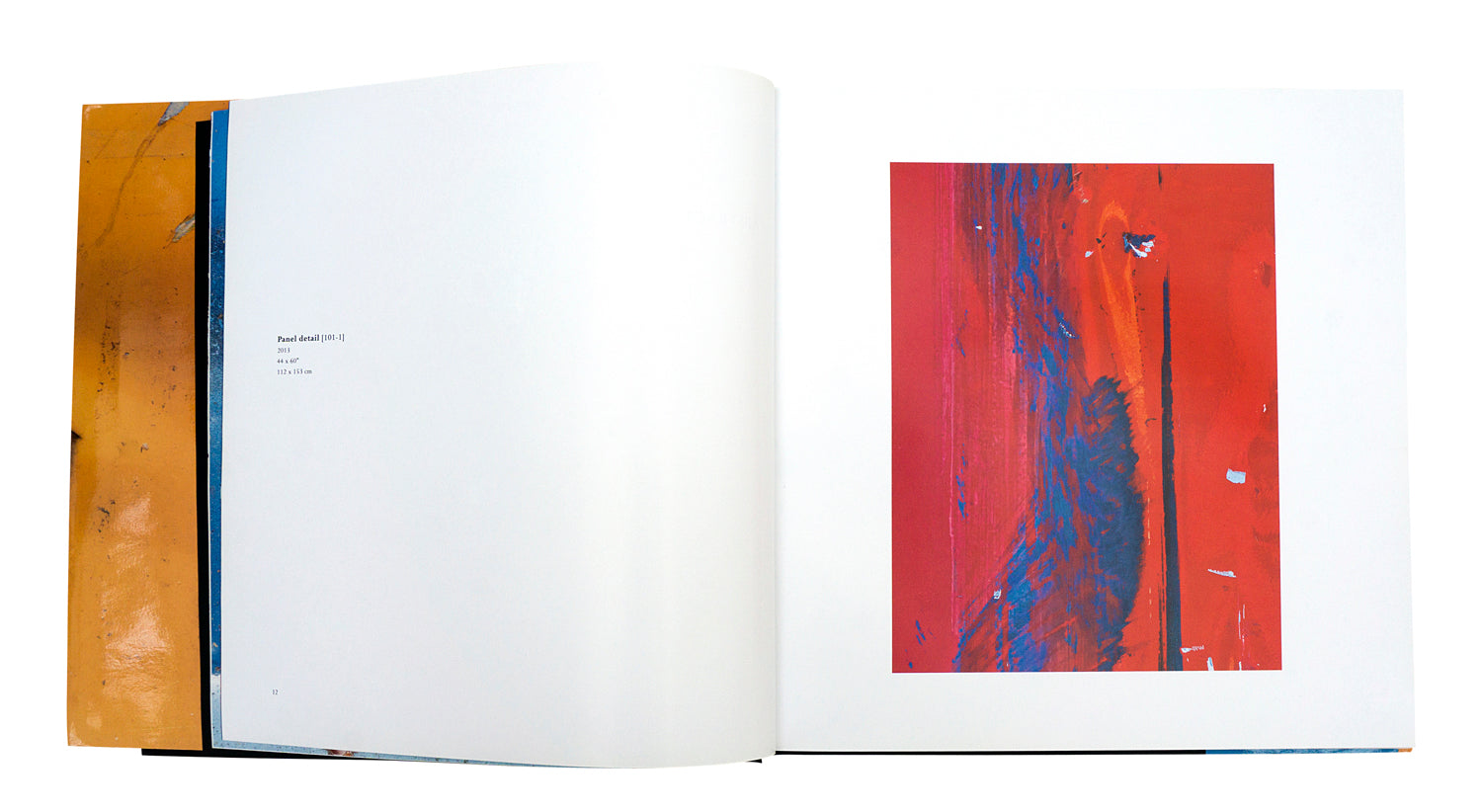

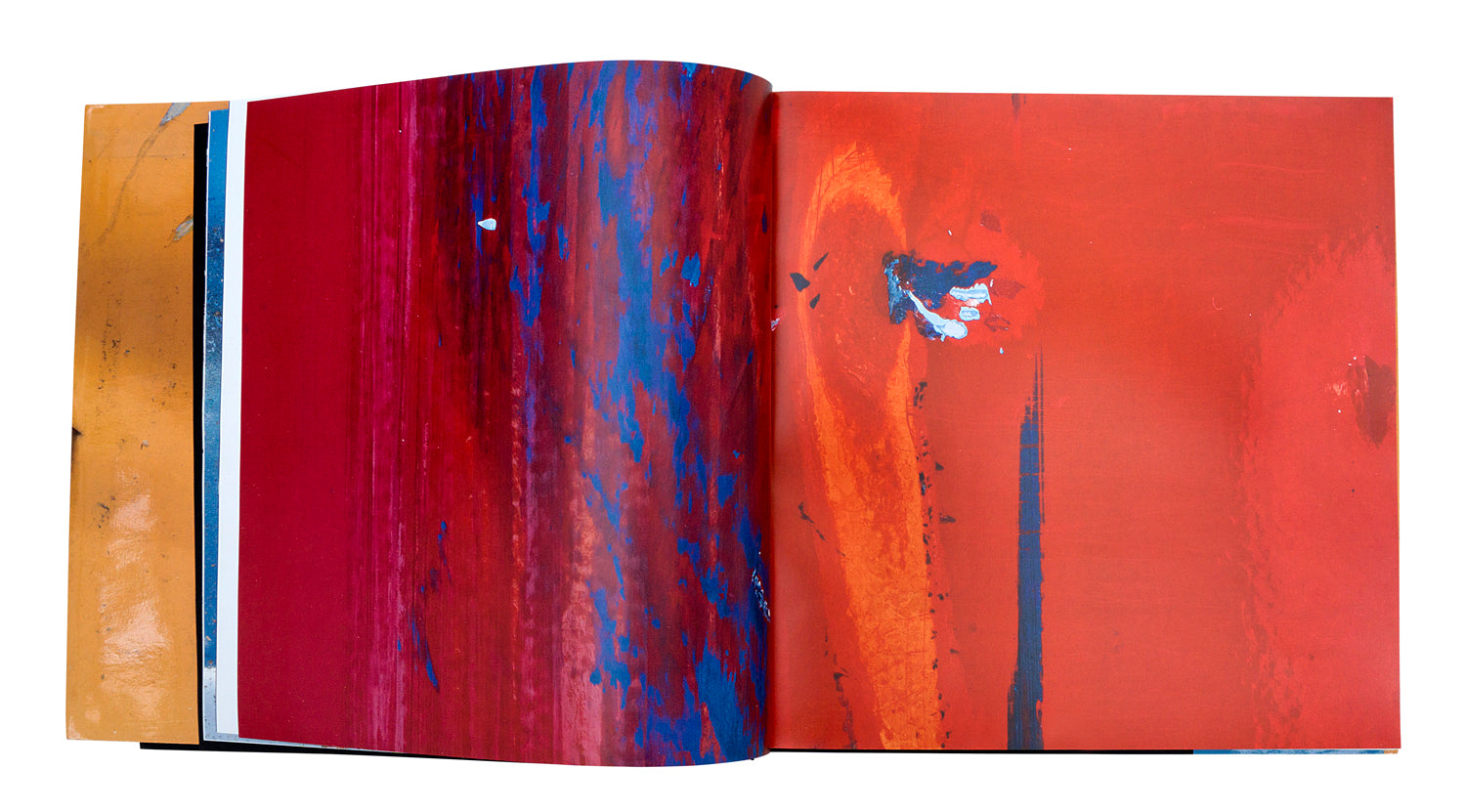

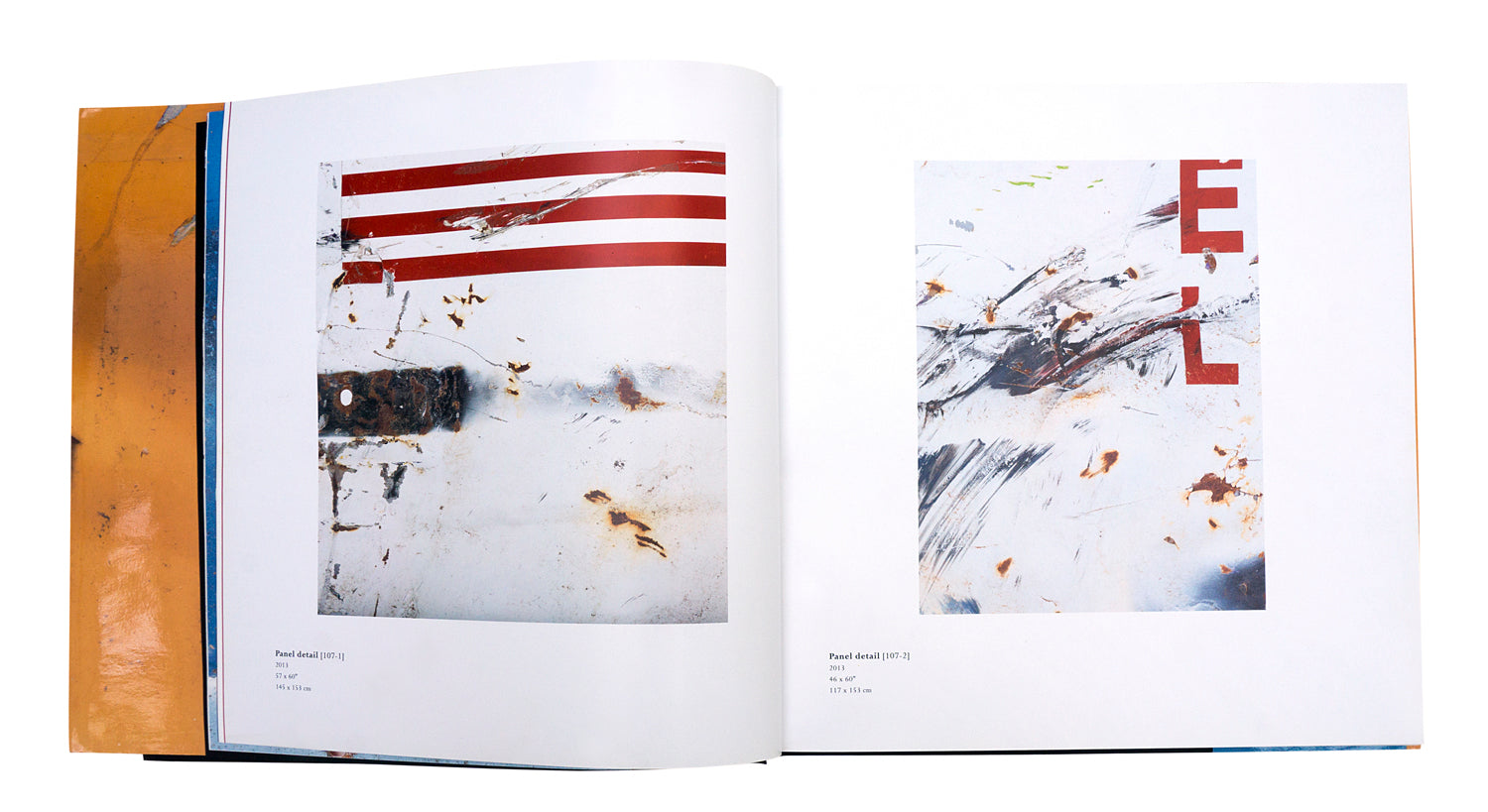

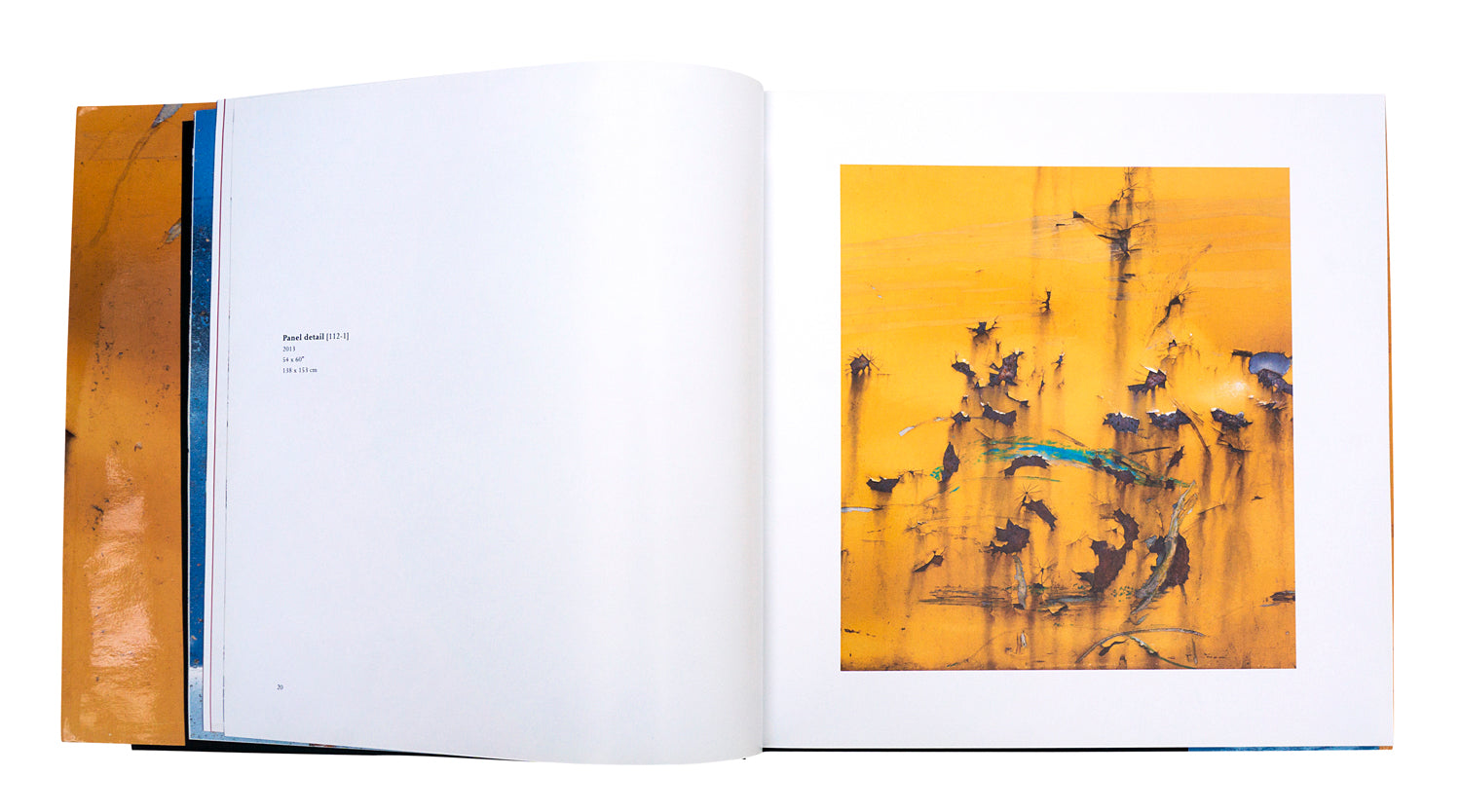

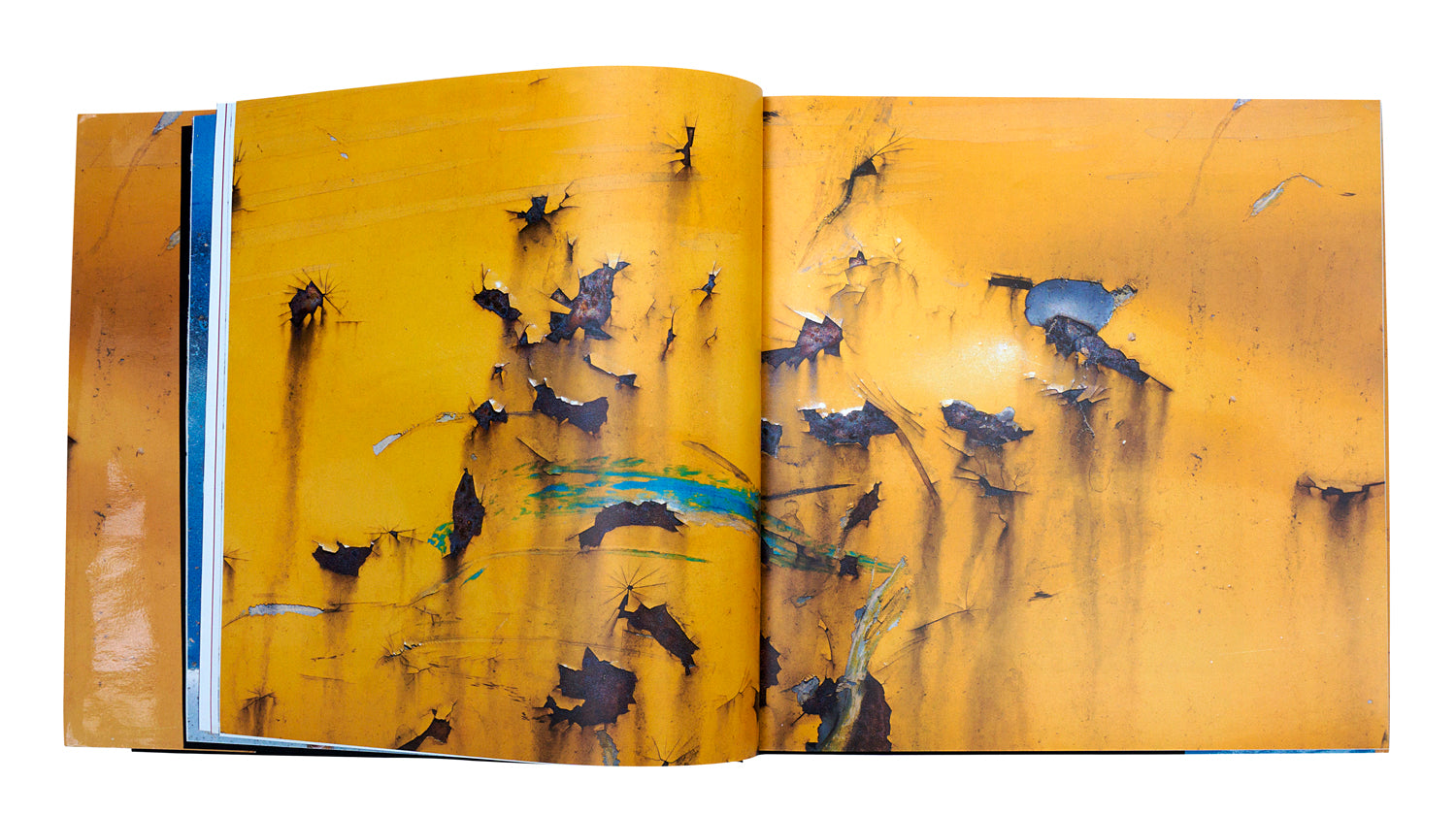

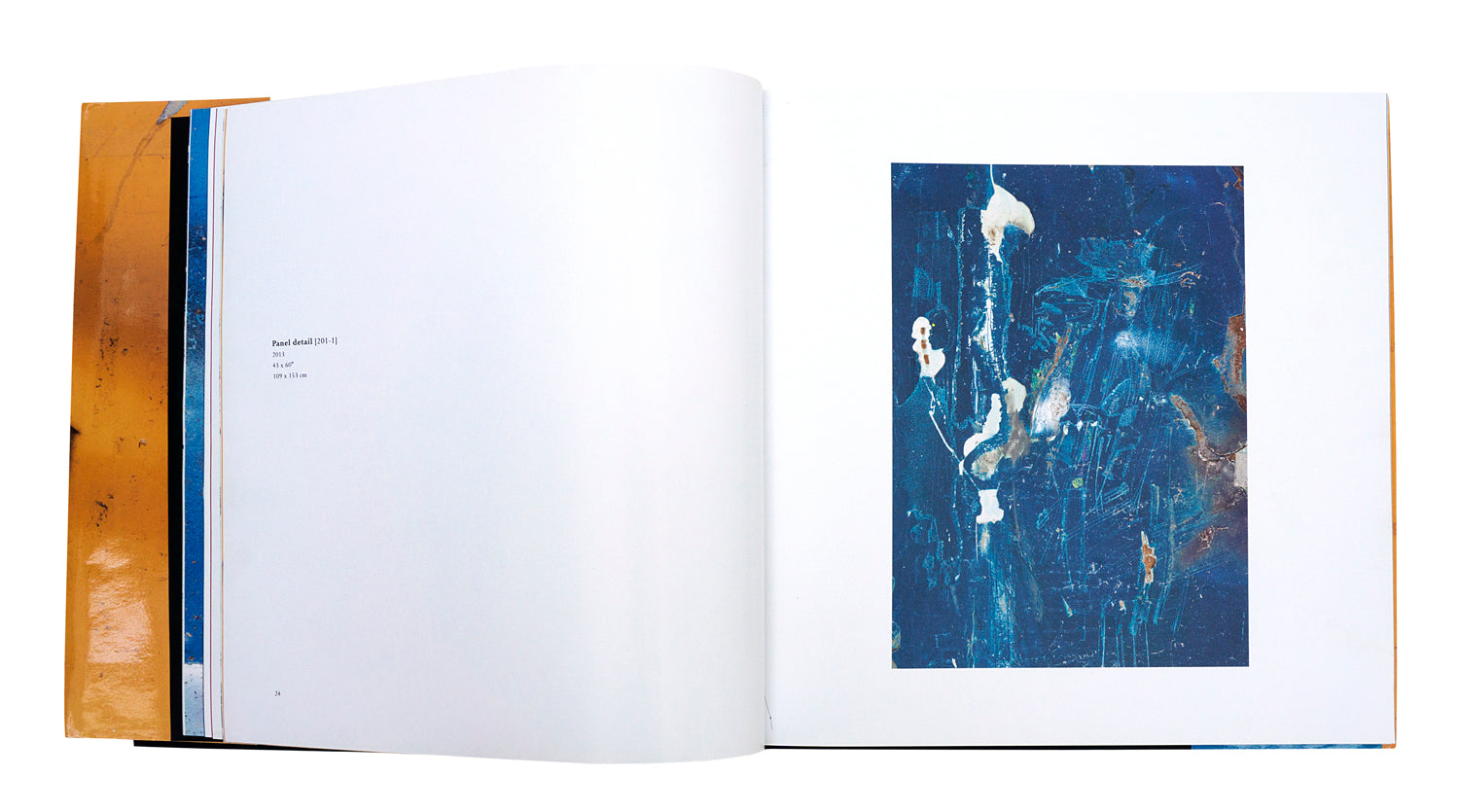

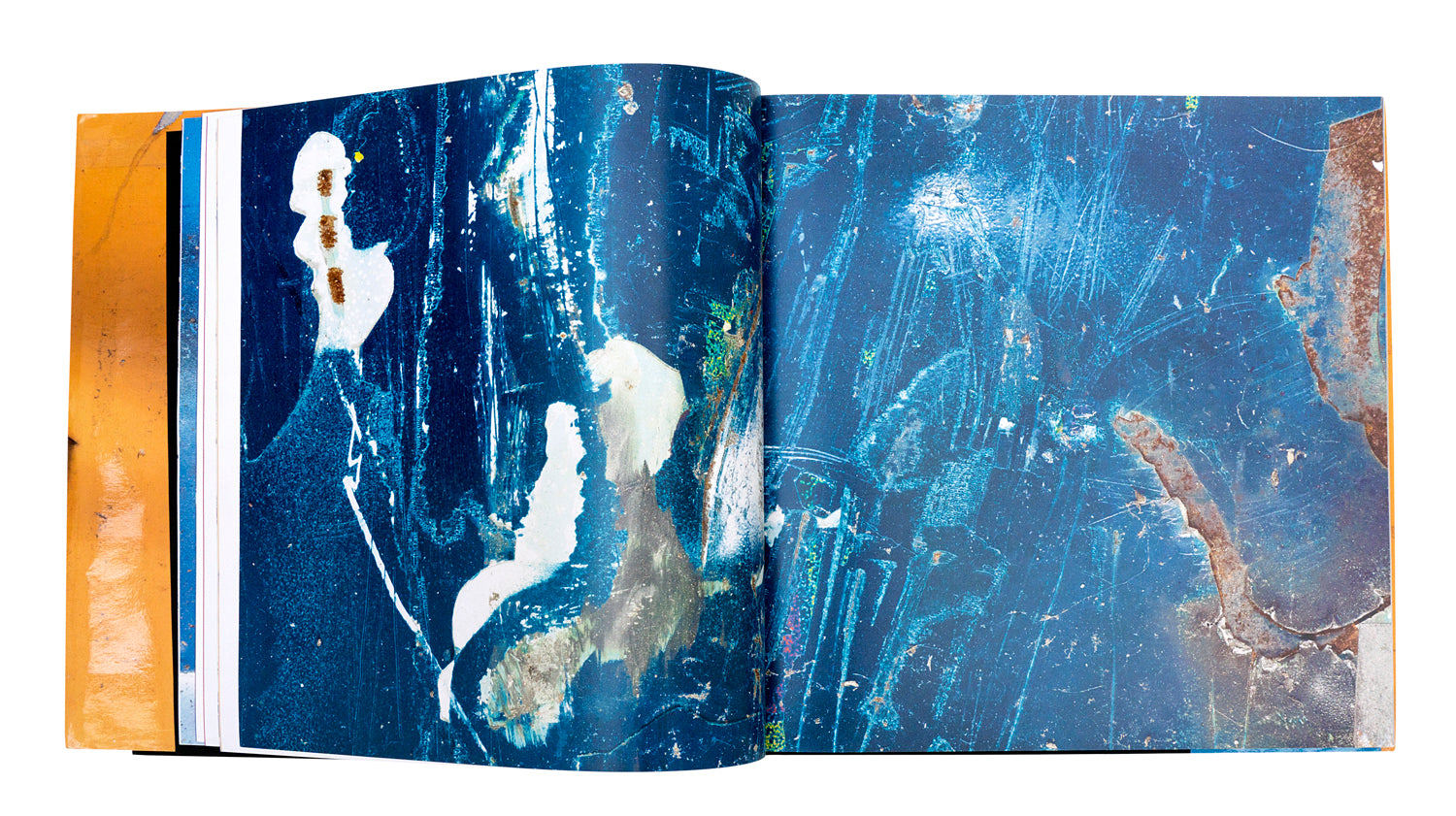

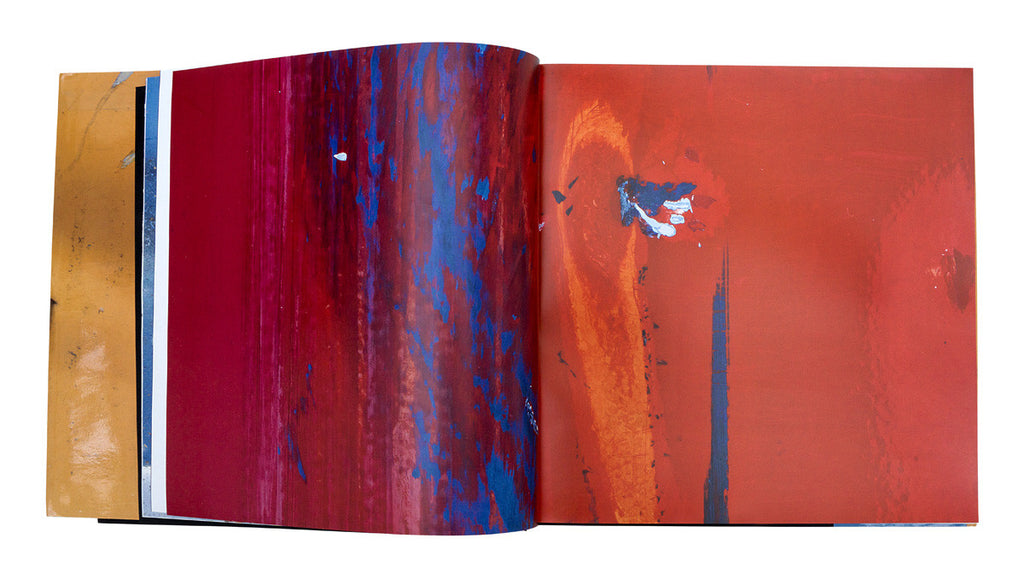

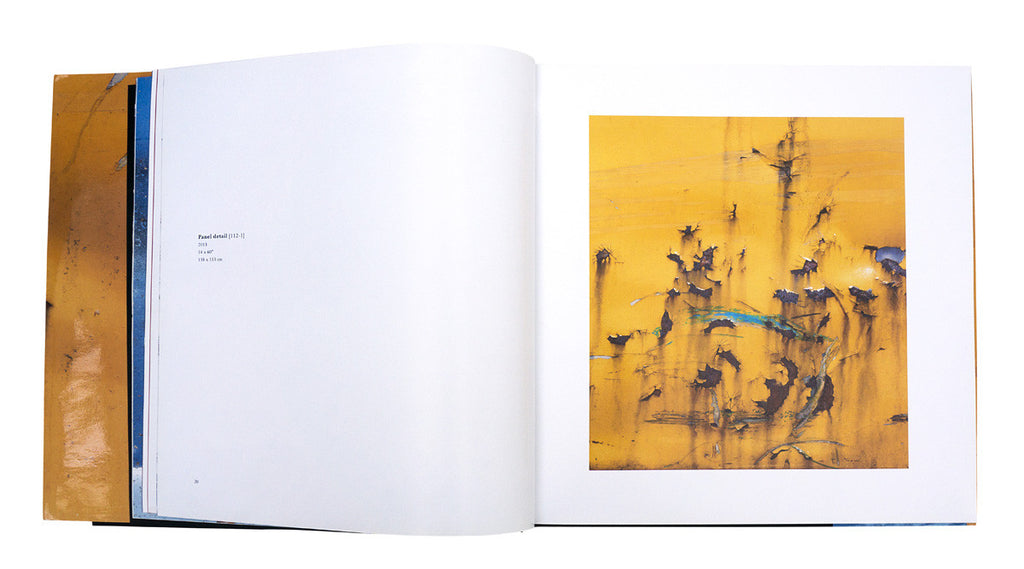

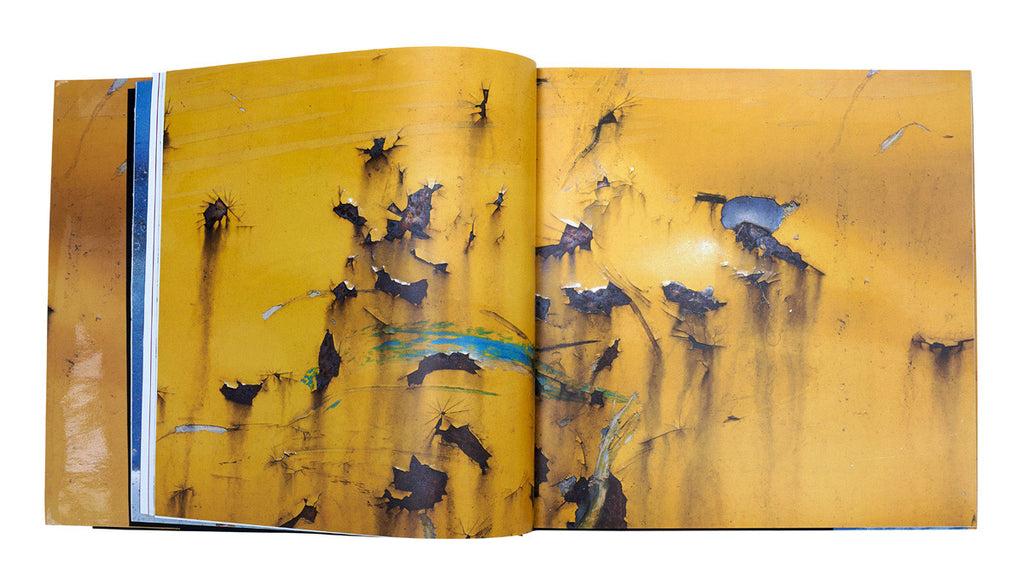

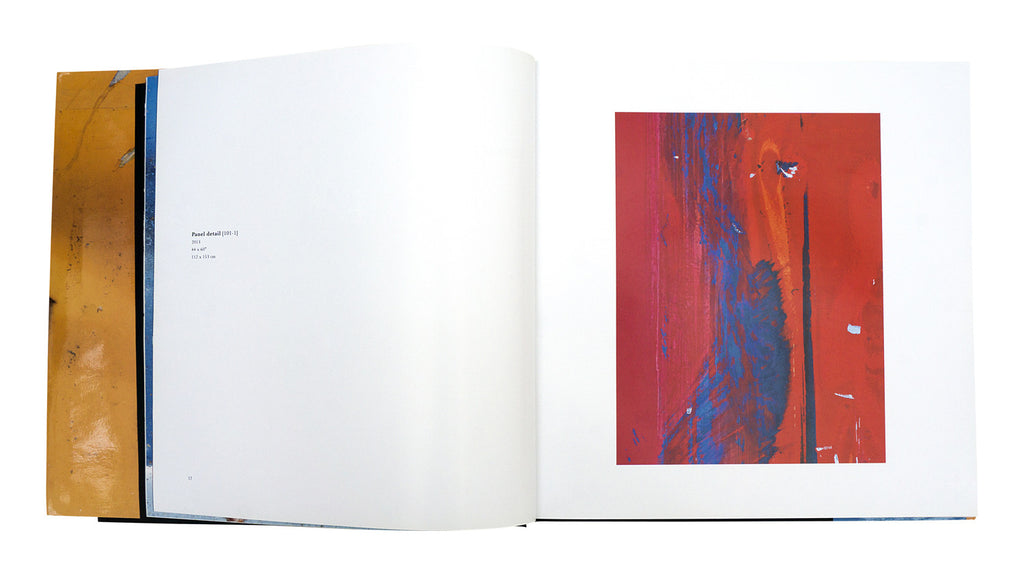

Take the largest series of photographs, for example. It would be a mistake to think of these as imitations of abstract painting. Dweck’s camera is forensic in its manic attention to what happens when fender meets quarter panel at seventy miles per hour. Facture here is a function of mass and acceleration. Paint and detailing are little more than sacrificial. Technically, the works are high-fidelity, dye-printed panels that eliminate any and all depth of field, the effect of which is to render them even more unfamiliar, even more unlike the car panels from which they derive. In fact, there is very little sense that these photographic prints are derivative of any pro-filmic thing, either car panel, abstract painting, billboard, road sign, or any other appropriately two-dimensional designed surface.

The point, of course, isn’t to invoke the whole, but to analyze the fragment, to drill down into its secrets. Any given panel may have been painted 20, 30, even 40 times, which means every scrape, every metal-on-metal contact at speed reveals something of that panel’s history (not the car’s, importantly, because “car” here is only rhetorical, an entity composed of any number of different components that have been raced in and as any number of different “cars”). In this, Dweck’s photography is a kind of industrial archaeology. The manufacturers of these cars, big American names such as Cadillac, Chevrolet, Oldsmobile, Pontiac, Ford, and others, aren’t making cars this big or this heavy anymore, so the drivers and their teams—family members and local gearheads—have to source increasingly scarce frames and parts from chop shops and junk yards.

And these are not the only artifacts that Dweck’s camera digs up. There are portraits of the drivers: sons of east Long Island for whom lures like the Hamptons or Shelter Island supply seasonal customers for their local area businesses, and likely the butts of many a joke, if not the objects of many an irritation. Folks from Amagansett buy a lot of cars, but probably have never built one. The drivers appear hard and proud. And Riverhead Raceway, also in Dweck’s sights, is their middle-class redoubt. The track, like the community, demands character. It’s akin to a triple-A baseball diamond, but without the wholesome Iowa farm boy bullshit. Then there are the pictures of parts, sandblasted and ghostly skeletal: wheels, springs, chassis. Uncovered and offered up as if by some archeologist of the future. Standing out of time and beyond any imagined use, they are the relics of a lost religion.

Taken together, Dweck’s photographs and prints give us something more than a mere “portrait” of Blunderbust culture, which they only capture obliquely anyhow. These cars, these people, this place, they are moving slowly, their time is winding down (the number of cars on the track is diminishing each year: a few years ago, there were 33 racing on any given Saturday night; last year there were only 22). This idiosyncratic pastime—racing big, heavy, stock American sedans on a small dangerous track—is out of step with the industrial world at large, the one that wants lighter and cleaner vehicles, higher tech entertainments, broader recognition, if not affirmation, for one’s profile and skills—which, it’s worth mentioning, when they are employed, will increasingly be put to fixing and operating a new generation of robotics that will do most of our future’s “making.”

Cars and car culture, obsolete and otherwise, are far from foreign to the history of recent art. One thinks of Ed Ruscha’s books, which mapped the natural habitat (gas stations, parking lots, the Sunset Strip) of the Los Angeles automobile; or of Richard Prince’s muscle car hoods made from fiberglass and Bondo. John Chamberlain’s sculptures loom large here too. But where Chamberlain’s practice is one that constantly reminds its viewers of the singular artistic will to material transformation that stands behind each and every work, Blunderbust offers up to view, in a wholly unelgiac way, the structural conditions (macroeconomic, demographic, technological) for which its aesthetics are merely effects—of collisions, of closures, of a fatalist persistence in the face of inevitable extinction. Against Chamberlain’s heroics, then, we have Blunderbust’s pathos. Look again at the panels. Dweck’s printing process strips out all of the camera’s, all of photography’s, conventional language in order to leave behind something apparently unmediated, like long-buried bone.

In this sense, Blunderbust is a picture of failing resistance, but resistance nonetheless; it’s a kind of defiant expression of commitment and community that cares little for life beyond the track. Call it ‘purposeful purposelessness’, which is another name for beauty.

- Michael Dweck: Blunderbust

- Large format hardcover: 30.5 x 30.5 cm (12 x 12 in.) 400 pages, 320 color plates.

- Release date: April 2016

- Interviews: TBD

- Published by Ditch Plains Press

- ISBN: TBD

- Printed and bound in US

- Clothbound with dust jacket

- First edition of 2000

Will also be available in a limited edition Art Edition Box Set with a book and a silver gelatin photograph, both signed by Michael Dweck

All color illustrations are color-separated and reproduced in the finest technique available today, which provides unequalled intensity and color range.

About Michael Dweck

Michael Dweck is an American photographer, filmmaker and visual artist.

His work has been featured in solo exhibitions around the world, and become part of important international art collections. Notable solo exhibitions include Montauk: The End, 2004, a paradisiacal and erotic surf narrative set on Long Island; Mermaids, 2009, which explored the female nude refracted by river waters; and Habana Libre, 2010; an intimate exploration of privileged artists in socialist Cuba, which made him the first living American artist to have a solo exhibition in Cuba. These and other works have also been published in large, limited-edition volumes.

Previously, Dweck studied fine arts at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York and went on to become a highly regarded Creative Director, receiving more than 40 international awards, including the coveted Gold Lion at the Cannes International Festival in France. Two of his long-form television pieces are part of the permanent film collection of The Museum of Modern Art in New York. Michael Dweck currently lives in New York City and Montauk, N.Y., where he is finishing his first feature-length film.

Mermaid 18. Weeki Wachee, Florida, 2007

Mermaid 18. Weeki Wachee, Florida, 2007  Mermaid 30. Aripeka, Florida, 2007

Mermaid 30. Aripeka, Florida, 2007  Mermaid 36. Miami, 2007

Mermaid 36. Miami, 2007  Mermaid 18b. Weeki Wachee, Florida, 2007

Mermaid 18b. Weeki Wachee, Florida, 2007  Mermaid 4b. Miami, 2007

Mermaid 4b. Miami, 2007  Mermaid 15. Weeki Wachee, 2007

Mermaid 15. Weeki Wachee, 2007  Mermaid 89. Miami, 2007

Mermaid 89. Miami, 2007  Mermaid 41. Miami, 2007

Mermaid 41. Miami, 2007  Mermaid 105. Miami, 2007

Mermaid 105. Miami, 2007  Mermaid 5. Weeki Wachee, Florida, 2007

Mermaid 5. Weeki Wachee, Florida, 2007  Mermaid 86. Miami, 2007

Mermaid 86. Miami, 2007  Mermaid 106. Miami, 2007

Mermaid 106. Miami, 2007  Mermaid 115. Weeki Wachee, Florida, 2007

Mermaid 115. Weeki Wachee, Florida, 2007  Mermaid 2. Miami, 2006

Mermaid 2. Miami, 2006  Mermaid 105 mural at Staley Wise exhibition 2014

Mermaid 105 mural at Staley Wise exhibition 2014  Mermaid 38. Miami, 2007

Mermaid 38. Miami, 2007  Mermaid 105 mural at Staley Wise Gallery exhibition, New York 2014

Mermaid 105 mural at Staley Wise Gallery exhibition, New York 2014  Mermaid 105 mural at Modernism exhibition, San Francisco 2015

Mermaid 105 mural at Modernism exhibition, San Francisco 2015  Michael Dweck: Mermaids exhibition at Robert Morat Galerie, Hamburg 2008

Michael Dweck: Mermaids exhibition at Robert Morat Galerie, Hamburg 2008  Michael Dweck: Mermaids exhibition at Robert Morat Galerie, Hamburg 2008

Michael Dweck: Mermaids exhibition at Robert Morat Galerie, Hamburg 2008  Michael Dweck:Mermaids exhibition at Staley Wise Gallery exhibition, New York 2014

Michael Dweck:Mermaids exhibition at Staley Wise Gallery exhibition, New York 2014

Michael Dweck: Mermaids

by Christopher Sweet

Whether diving in the blue refractions of a swimming pool or suspended like a seraph in the cool, pellucid depths of a spring or emerging tentatively onto a rocky shore, Michael Dweck’s mermaids are lovely and aloof and bare of all raiment but for their beautiful manes and the elemental draperies that surround them. Water, light, and lens converge to capture in modern guise the elusive creature of myth.

A diver plunges into deep dark water in a billowing ball gown of bubbles and foam. A figure rises slowly in the dark water, her back arched, her head back, her hair like exotic plumage spreading behind her. Another darts through the water in a roiling pool, her physical form appearing and disappearing in the distorting glass of the agitated waters. Yet another circles like a rippling wraith, a shadowy form, her hair in thick swirling liquid coils. The allure of these beautiful figures is made more compelling by their elusiveness, their strange remoteness, absracted as they are by this medium of water, immersed in this place beyond terra firma as in a dream. They would seem to have slipped the bonds of the mundane world into another element where the senses are altered, the laws are different, and only the elect are allowed. Even so, seeing them in Dweck’s photographs, they have the decided attraction of being real. We know they are of flesh and blood, their delectable bodies caressed by the enveloping waters and kissed by the play of light from above, their likenesses and perhaps a bit of their soul having been stolen by the intruder photographer—and pored over by unseen eyes.

Raised on Long Island near the ocean, Dweck often went night fishing along the south shore and off Montauk. When out fishing on moonlit nights, Dweck was always intrigued by the mysterious forms of fish passing swiftly by just under the surface like fleeting shadows, and he fantasized about falling overboard into the black waters and encountering those evanescent shapes and finding them to be beautiful women. The ancient allure of the mermaid. And so, having completed his project on the old fishing community of Montauk and its surfing subculture—the nostalgia for a real world paradise lost, Dweck was exploring the theme of the female nude in water. He began his new project in Amagansett and Montauk, photographing friends in pools and lake shallows from above, mostly at night. With a change of season, he flew south to Miami and continued to photograph in pools and near the ocean. Not satisfied with photographing from above, he began to look for a setting which would allow him to photograph underwater and came across the Weeki Wachee Spring, famed for its mermaid shows, where the water is clear, pure, of a light blue-green cast, and where he could photograph from an aquarium-like theater built into the bank of the eponymous river, or from a clear tank partially submerged in the river, and while swimming with his subjects.

When checking out the Weeki Wachee River, Dweck met a local young beauty who had been raised in nearby Aripeka, an island fishing village of a dozen or so families on the coast, and began photographing her. She has spent all her life in and on the gulf waters and in the many springs that surround the island, and she performed in the mermaid shows. In Aripeka the houses are built on stilts and babies are taught to hold their breath underwater. Making their living from the sea, surrounded by it, playing in it, growing up on the water, in a culture apart, Dweck was fascinated by the girl’s story and lifestyle—and the idea of the mermaid. And so the concept of photographing mermaids came fully into focus. Through the first girl, Dweck met other island girls, some of whom could hold their breath underwater for as long as five or six minutes. He photographed them alone, together, and at play, but mostly at night in the depths of the river.

Dweck’s image of the mermaid does not dwell on turgid fin de siècle fantasies nor the kitsch of Hollywood. He is enthralled by the female form, but also by the movement of water, by the play of light and shadow, distortion and reflection. He is interested in a sense of place and a place in time and the authentic inhabitants of such a place, but in this project he eschews telling details of the larger context and personality to focus closely on the nude female body isolated and abstracted by the fluid environment. In his vision of the mermaid he nonetheless exposes an aspect of life that is lived naturally as if uncorrupted, indeed pure. Whatever the circumstances of the lives of his subjects, they are members of a unique world. They are as they say “waterbabies” and it takes one borne of the water as they have been to connect deeply with them. Certainly they do not escape the claims of the real world, and yet one feels that for a time they do. They have a way of retreating, of withdrawal, of setting themselves outside of daily life, if only briefly, if only as long as a very deep breath.

Photographed underwater, whether from behind glass or otherwise, the figure floats in the field of vision as if front and back, top and bottom, and sides all change places at will at all times. Despite the glass wall, the river is not a proscenium. Only the light projected or filtering from above orients the viewer to the relative position of the body suspended in the water. Elegant postures and gestures and erotic positions are assumed unself-consciously and as easily relaxed. The veils and broideries of water, still and in motion, of shadow and light, conceal and distort as much as reveal. The fetching form of a pretty young girl may transmogrify into a raw mass of muscle, like a Francis Bacon painting, or strike a pose as exquisite as a classical ballet dancer on point. Torsos and limbs and features may dissolve in a painterly swirl, as of late de Kooning. We rarely catch a glimpse of their faces, only occasionally a nose or a nipple or a navel.

In legend and lore, the mermaid is a symbol of fatal seduction. She represents the self-destructive aspect of desire, the toxic allure of the unattainable. Like Ulysses one must be bound hard and fast to the mast of reality to successfully escape the illusions of unbridled passion. And yet the mermaid dwells in the sea and her sisters in ponds and lakes and springs. Water is the source of life, the essential means of purification, and the elemental locus of regeneration. Dweck’s mermaids are sensual and alluring, but also free and unfettered. The indeterminate world they inhabit, however briefly, is a private, peaceful place where they may find a serenity not possible in the world on dry land. But there is also something ruthless in the photographer’s somatic divagations, in the optical distortions of the lithesome bodies that he seizes upon through the roiling waters. It is the ruthlessness of the hungry eye of the photographer, who, like mermaids of yore, is a predator himself.

In the nineteenth century, images of mermaids abounded. The enticement of such images, as in the pallid picturebook paintings of a Waterhouse or a Burne-Jones, teased a Victorian sensibility. In America, the imperatives of popular culture have tended to domesticate the mysterious and eliminate dread and submerge the erotic in a cloying cuteness, so that the femme fatale figure of the mermaid has been reduced to an anodyne animation. The aquatic world of Dweck’s, however, is rather more luxe, calme, et volupté—where Matisse’s nymphs and dancing maenads or perhaps Yves Klein’s naked blue living female “paintbrushes” have gotten swept up in the blue-green veils of a Morris Louis canvas. In Dweck’s abstracting, painterly vision of the mermaid, where the depth of field of his lens is iterated by the water’s depths, he offers a vision of untrammeled beauty, without vanity or pretense, but natural, elegant, at times effervescent. The enchantment of place and physical charm, the shedding of clothing and psychic baggage, the meditative isolation of the underwater world, and the baptismal cleansing of the waters produce a transformation that only being truly in one’s element may confer—at least “till human voices wake us, and we drown.”

Michael Dweck: BLUNDERBUST

Interviews: TBA

Published by Ditch Plains Press, New York

Release date: 2016

Michael Dweck, Blunderbust

By Jonathan T.D. Neil

“No one knows where the name came from.” So says the driver of a “Blunderbust” race car, a class of big (minimum 115 inch wheelbase) and heavy (almost two ton) stock cars that run most Saturday nights at Long Island’s Riverhead Raceway—the oldest operational track in the U.S.—and nowhere else. The racing is rough. The drivers are rough, and scarred, just like their cars. Compared to Blunderbust racing, Nascar looks like a cricket match—manicured, mannered, lillywhite.

Blunderbust culture is Michael Dweck’s subject—something of a breakthrough for the photographer, not only because it marks a significant departure from his previous series of portraits and nudes but also because this new body of work must be classified as something other than merely conceptual or commercial or documentary or formal or as some high-art synthesis or short-circuiting of these. As a photographer, Dweck approaches this culture like a renegade anthropologist, a fascinated outsider whose curiosity and respect have gained him access to a disappearing tribe. His point, however, is not to document this culture, to freeze it in time for the archive, in a gesture of “this once was”—though Dweck has produced a documentary film that does some of that. Rather, Dweck’s photographs explore a more subtle language of forms and marks and images that this Blunderbust culture “speaks.”

Take the largest series of photographs, for example. It would be a mistake to think of these as imitations of abstract painting. Dweck’s camera is forensic in its manic attention to what happens when fender meets quarter panel at seventy miles per hour. Facture here is a function of mass and acceleration. Paint and detailing are little more than sacrificial. Technically, the works are high-fidelity, dye-printed panels that eliminate any and all depth of field, the effect of which is to render them even more unfamiliar, even more unlike the car panels from which they derive. In fact, there is very little sense that these photographic prints are derivative of any pro-filmic thing, either car panel, abstract painting, billboard, road sign, or any other appropriately two-dimensional designed surface.

The point, of course, isn’t to invoke the whole, but to analyze the fragment, to drill down into its secrets. Any given panel may have been painted 20, 30, even 40 times, which means every scrape, every metal-on-metal contact at speed reveals something of that panel’s history (not the car’s, importantly, because “car” here is only rhetorical, an entity composed of any number of different components that have been raced in and as any number of different “cars”). In this, Dweck’s photography is a kind of industrial archaeology. The manufacturers of these cars, big American names such as Cadillac, Chevrolet, Oldsmobile, Pontiac, Ford, and others, aren’t making cars this big or this heavy anymore, so the drivers and their teams—family members and local gearheads—have to source increasingly scarce frames and parts from chop shops and junk yards.

And these are not the only artifacts that Dweck’s camera digs up. There are portraits of the drivers: sons of east Long Island for whom lures like the Hamptons or Shelter Island supply seasonal customers for their local area businesses, and likely the butts of many a joke, if not the objects of many an irritation. Folks from Amagansett buy a lot of cars, but probably have never built one. The drivers appear hard and proud. And Riverhead Raceway, also in Dweck’s sights, is their middle-class redoubt. The track, like the community, demands character. It’s akin to a triple-A baseball diamond, but without the wholesome Iowa farm boy bullshit. Then there are the pictures of parts, sandblasted and ghostly skeletal: wheels, springs, chassis. Uncovered and offered up as if by some archeologist of the future. Standing out of time and beyond any imagined use, they are the relics of a lost religion.

Taken together, Dweck’s photographs and prints give us something more than a mere “portrait” of Blunderbust culture, which they only capture obliquely anyhow. These cars, these people, this place, they are moving slowly, their time is winding down (the number of cars on the track is diminishing each year: a few years ago, there were 33 racing on any given Saturday night; last year there were only 22). This idiosyncratic pastime—racing big, heavy, stock American sedans on a small dangerous track—is out of step with the industrial world at large, the one that wants lighter and cleaner vehicles, higher tech entertainments, broader recognition, if not affirmation, for one’s profile and skills—which, it’s worth mentioning, when they are employed, will increasingly be put to fixing and operating a new generation of robotics that will do most of our future’s “making.”

Cars and car culture, obsolete and otherwise, are far from foreign to the history of recent art. One thinks of Ed Ruscha’s books, which mapped the natural habitat (gas stations, parking lots, the Sunset Strip) of the Los Angeles automobile; or of Richard Prince’s muscle car hoods made from fiberglass and Bondo. John Chamberlain’s sculptures loom large here too. But where Chamberlain’s practice is one that constantly reminds its viewers of the singular artistic will to material transformation that stands behind each and every work, Blunderbust offers up to view, in a wholly unelgiac way, the structural conditions (macroeconomic, demographic, technological) for which its aesthetics are merely effects—of collisions, of closures, of a fatalist persistence in the face of inevitable extinction. Against Chamberlain’s heroics, then, we have Blunderbust’s pathos. Look again at the panels. Dweck’s printing process strips out all of the camera’s, all of photography’s, conventional language in order to leave behind something apparently unmediated, like long-buried bone.

In this sense, Blunderbust is a picture of failing resistance, but resistance nonetheless; it’s a kind of defiant expression of commitment and community that cares little for life beyond the track. Call it ‘purposeful purposelessness’, which is another name for beauty.

- Michael Dweck: Blunderbust

- Large format hardcover: 30.5 x 30.5 cm (12 x 12 in.) 400 pages, 320 color plates.

- Release date: April 2016

- Interviews: TBD

- Published by Ditch Plains Press

- ISBN: TBD

- Printed and bound in US

- Clothbound with dust jacket

- First edition of 2000

Will also be available in a limited edition Art Edition Box Set with a book and a silver gelatin photograph, both signed by Michael Dweck

All color illustrations are color-separated and reproduced in the finest technique available today, which provides unequalled intensity and color range.

About Michael Dweck

Michael Dweck is an American photographer, filmmaker and visual artist.

His work has been featured in solo exhibitions around the world, and become part of important international art collections. Notable solo exhibitions include Montauk: The End, 2004, a paradisiacal and erotic surf narrative set on Long Island; Mermaids, 2009, which explored the female nude refracted by river waters; and Habana Libre, 2010; an intimate exploration of privileged artists in socialist Cuba, which made him the first living American artist to have a solo exhibition in Cuba. These and other works have also been published in large, limited-edition volumes.

Previously, Dweck studied fine arts at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York and went on to become a highly regarded Creative Director, receiving more than 40 international awards, including the coveted Gold Lion at the Cannes International Festival in France. Two of his long-form television pieces are part of the permanent film collection of The Museum of Modern Art in New York. Michael Dweck currently lives in New York City and Montauk, N.Y., where he is finishing his first feature-length film.

Mermaid 18. Weeki Wachee, Florida, 2007

Mermaid 18. Weeki Wachee, Florida, 2007  Mermaid 30. Aripeka, Florida, 2007

Mermaid 30. Aripeka, Florida, 2007  Mermaid 36. Miami, 2007

Mermaid 36. Miami, 2007  Mermaid 18b. Weeki Wachee, Florida, 2007

Mermaid 18b. Weeki Wachee, Florida, 2007  Mermaid 4b. Miami, 2007

Mermaid 4b. Miami, 2007  Mermaid 15. Weeki Wachee, 2007

Mermaid 15. Weeki Wachee, 2007  Mermaid 89. Miami, 2007

Mermaid 89. Miami, 2007  Mermaid 41. Miami, 2007

Mermaid 41. Miami, 2007  Mermaid 105. Miami, 2007

Mermaid 105. Miami, 2007  Mermaid 5. Weeki Wachee, Florida, 2007

Mermaid 5. Weeki Wachee, Florida, 2007  Mermaid 86. Miami, 2007

Mermaid 86. Miami, 2007  Mermaid 106. Miami, 2007

Mermaid 106. Miami, 2007  Mermaid 115. Weeki Wachee, Florida, 2007

Mermaid 115. Weeki Wachee, Florida, 2007  Mermaid 2. Miami, 2006

Mermaid 2. Miami, 2006  Mermaid 105 mural at Staley Wise exhibition 2014

Mermaid 105 mural at Staley Wise exhibition 2014  Mermaid 38. Miami, 2007

Mermaid 38. Miami, 2007  Mermaid 105 mural at Staley Wise Gallery exhibition, New York 2014

Mermaid 105 mural at Staley Wise Gallery exhibition, New York 2014  Mermaid 105 mural at Modernism exhibition, San Francisco 2015

Mermaid 105 mural at Modernism exhibition, San Francisco 2015  Michael Dweck: Mermaids exhibition at Robert Morat Galerie, Hamburg 2008

Michael Dweck: Mermaids exhibition at Robert Morat Galerie, Hamburg 2008  Michael Dweck: Mermaids exhibition at Robert Morat Galerie, Hamburg 2008

Michael Dweck: Mermaids exhibition at Robert Morat Galerie, Hamburg 2008  Michael Dweck:Mermaids exhibition at Staley Wise Gallery exhibition, New York 2014

Michael Dweck:Mermaids exhibition at Staley Wise Gallery exhibition, New York 2014

Michael Dweck: Mermaids

by Christopher Sweet

Whether diving in the blue refractions of a swimming pool or suspended like a seraph in the cool, pellucid depths of a spring or emerging tentatively onto a rocky shore, Michael Dweck’s mermaids are lovely and aloof and bare of all raiment but for their beautiful manes and the elemental draperies that surround them. Water, light, and lens converge to capture in modern guise the elusive creature of myth.

A diver plunges into deep dark water in a billowing ball gown of bubbles and foam. A figure rises slowly in the dark water, her back arched, her head back, her hair like exotic plumage spreading behind her. Another darts through the water in a roiling pool, her physical form appearing and disappearing in the distorting glass of the agitated waters. Yet another circles like a rippling wraith, a shadowy form, her hair in thick swirling liquid coils. The allure of these beautiful figures is made more compelling by their elusiveness, their strange remoteness, absracted as they are by this medium of water, immersed in this place beyond terra firma as in a dream. They would seem to have slipped the bonds of the mundane world into another element where the senses are altered, the laws are different, and only the elect are allowed. Even so, seeing them in Dweck’s photographs, they have the decided attraction of being real. We know they are of flesh and blood, their delectable bodies caressed by the enveloping waters and kissed by the play of light from above, their likenesses and perhaps a bit of their soul having been stolen by the intruder photographer—and pored over by unseen eyes.

Raised on Long Island near the ocean, Dweck often went night fishing along the south shore and off Montauk. When out fishing on moonlit nights, Dweck was always intrigued by the mysterious forms of fish passing swiftly by just under the surface like fleeting shadows, and he fantasized about falling overboard into the black waters and encountering those evanescent shapes and finding them to be beautiful women. The ancient allure of the mermaid. And so, having completed his project on the old fishing community of Montauk and its surfing subculture—the nostalgia for a real world paradise lost, Dweck was exploring the theme of the female nude in water. He began his new project in Amagansett and Montauk, photographing friends in pools and lake shallows from above, mostly at night. With a change of season, he flew south to Miami and continued to photograph in pools and near the ocean. Not satisfied with photographing from above, he began to look for a setting which would allow him to photograph underwater and came across the Weeki Wachee Spring, famed for its mermaid shows, where the water is clear, pure, of a light blue-green cast, and where he could photograph from an aquarium-like theater built into the bank of the eponymous river, or from a clear tank partially submerged in the river, and while swimming with his subjects.

When checking out the Weeki Wachee River, Dweck met a local young beauty who had been raised in nearby Aripeka, an island fishing village of a dozen or so families on the coast, and began photographing her. She has spent all her life in and on the gulf waters and in the many springs that surround the island, and she performed in the mermaid shows. In Aripeka the houses are built on stilts and babies are taught to hold their breath underwater. Making their living from the sea, surrounded by it, playing in it, growing up on the water, in a culture apart, Dweck was fascinated by the girl’s story and lifestyle—and the idea of the mermaid. And so the concept of photographing mermaids came fully into focus. Through the first girl, Dweck met other island girls, some of whom could hold their breath underwater for as long as five or six minutes. He photographed them alone, together, and at play, but mostly at night in the depths of the river.

Dweck’s image of the mermaid does not dwell on turgid fin de siècle fantasies nor the kitsch of Hollywood. He is enthralled by the female form, but also by the movement of water, by the play of light and shadow, distortion and reflection. He is interested in a sense of place and a place in time and the authentic inhabitants of such a place, but in this project he eschews telling details of the larger context and personality to focus closely on the nude female body isolated and abstracted by the fluid environment. In his vision of the mermaid he nonetheless exposes an aspect of life that is lived naturally as if uncorrupted, indeed pure. Whatever the circumstances of the lives of his subjects, they are members of a unique world. They are as they say “waterbabies” and it takes one borne of the water as they have been to connect deeply with them. Certainly they do not escape the claims of the real world, and yet one feels that for a time they do. They have a way of retreating, of withdrawal, of setting themselves outside of daily life, if only briefly, if only as long as a very deep breath.

Photographed underwater, whether from behind glass or otherwise, the figure floats in the field of vision as if front and back, top and bottom, and sides all change places at will at all times. Despite the glass wall, the river is not a proscenium. Only the light projected or filtering from above orients the viewer to the relative position of the body suspended in the water. Elegant postures and gestures and erotic positions are assumed unself-consciously and as easily relaxed. The veils and broideries of water, still and in motion, of shadow and light, conceal and distort as much as reveal. The fetching form of a pretty young girl may transmogrify into a raw mass of muscle, like a Francis Bacon painting, or strike a pose as exquisite as a classical ballet dancer on point. Torsos and limbs and features may dissolve in a painterly swirl, as of late de Kooning. We rarely catch a glimpse of their faces, only occasionally a nose or a nipple or a navel.

In legend and lore, the mermaid is a symbol of fatal seduction. She represents the self-destructive aspect of desire, the toxic allure of the unattainable. Like Ulysses one must be bound hard and fast to the mast of reality to successfully escape the illusions of unbridled passion. And yet the mermaid dwells in the sea and her sisters in ponds and lakes and springs. Water is the source of life, the essential means of purification, and the elemental locus of regeneration. Dweck’s mermaids are sensual and alluring, but also free and unfettered. The indeterminate world they inhabit, however briefly, is a private, peaceful place where they may find a serenity not possible in the world on dry land. But there is also something ruthless in the photographer’s somatic divagations, in the optical distortions of the lithesome bodies that he seizes upon through the roiling waters. It is the ruthlessness of the hungry eye of the photographer, who, like mermaids of yore, is a predator himself.

In the nineteenth century, images of mermaids abounded. The enticement of such images, as in the pallid picturebook paintings of a Waterhouse or a Burne-Jones, teased a Victorian sensibility. In America, the imperatives of popular culture have tended to domesticate the mysterious and eliminate dread and submerge the erotic in a cloying cuteness, so that the femme fatale figure of the mermaid has been reduced to an anodyne animation. The aquatic world of Dweck’s, however, is rather more luxe, calme, et volupté—where Matisse’s nymphs and dancing maenads or perhaps Yves Klein’s naked blue living female “paintbrushes” have gotten swept up in the blue-green veils of a Morris Louis canvas. In Dweck’s abstracting, painterly vision of the mermaid, where the depth of field of his lens is iterated by the water’s depths, he offers a vision of untrammeled beauty, without vanity or pretense, but natural, elegant, at times effervescent. The enchantment of place and physical charm, the shedding of clothing and psychic baggage, the meditative isolation of the underwater world, and the baptismal cleansing of the waters produce a transformation that only being truly in one’s element may confer—at least “till human voices wake us, and we drown.”

Manhattan

Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street

New York, NY 10019-5497

212.708.9703

Staley Wise Gallery

560 Broadway

New York, New York 10012

212.966.6223

photo@staleywise.com

International Center of Photography Museum

1133 Sixth Avenue @ 43rd Street

New York, New York 10036

212.857.0002

HomeNature

7 W 18th St.

New York, NY 10011

212.675.4663

matt@homenature.com

Modernism, Inc

685 Market St., Suite 290

San Francisco, CA 94105

415.541.0461

danielle@modernisminc.com

Fahey Klein

148 North La Brea

Los Angeles, California 90036

323.934.2250

contact@faheykleingallery.com

Arcana: Books on the Arts

8675 Washington Boulevard

Culver City, California 90232

310.458.1499

sales@arcanabooks.com

Nicole Henry Fine Arts

501 Fern Street Suite 103

West Palm Beach, FL 33401

561.714.4262

nicole@nicolehenryfineart.com

Books and Books

933 Lincoln Road

Miami Beach, Florida 33139

305.532.3222

orders@booksandbooks.com

Books and Books

265 Argon Avenue

Coral Gables, Florida 33134

305.442.4408

orders@booksandbooks.com

Dean Project

1234 Washington Avenue, 3rd floor

Miami Beach, FL 33139

1.800.791.0830

info@deanproject.com

Belgium

Jablonka Maruani Mercier Gallery

Rue de la Régence 17

1000 Brussels

Belgium

+32 (0)475 25 16 75

serge@jmmgallery.com

Japan

Blitz House

6-20-29 Shimomeguro

Meguro-ku, Tokyo

81-(0)3-3714-0552

fwnf3039@mb.infoweb.ne.jp

Canada

Izzy Gallery

106 Yorkville Avenue

Toronto,Ontario

M5R 1B9

416.922.1666

izzygallery@gmail.com

Damir.izzygallery@gmail.com

France

Acte2 Gallery

9 rue des Arquebusiers

Paris 75003br

00 33 (0) 1 57 40 60 54

renaud@acte2galerie.com